Will the new year bring effective, tough federal anti-spyware legislation? Congress’s attempt to block spam, the CAN-Spam Act, was by most reports unsuccessful. But I think Congress could do better with spyware. Spammers tend to be small, fly-by-night operations — hard for lawyers and courts to find and stop. In contrast, many spyware companies have fancy headquarters and major investors. (See my recently-released list.)

So tough anti-spyware legislation could find and stop the biggest spyware offenders. Unfortunately, from what I’ve seen so far, any new anti-spyware law will be surprisingly lax. The major effort so far is Rep. Mary Bono‘s recently-reintroduced SPY Act (H.R.29). Her intentions are surely good, and Reuters has called her bill “tough.” But as I read the bill, it’s riddled with loopholes and almost certain to be ineffective. (Ed Felten offered this unhopeful assessment in his predictions for technology policy in 2005, and Ed Foster has been saying so since June.)

The Sec.2. “Deceptive Acts” Prohibition — and Its Loopholes

Bono’s bill begins with eighteen specific practices to be prohibited. From taking control of a computer and using it to send “unsolicited information” (e.g. junk email) (Sec.2.(a)(1)(A)), to using a keystroke logger ((a)(3)), to changing home pages ((a)(2)(A)) and bookmarks ((a)(2)(C)), the bill prohibits a veritable laundry list of controversial activities.

But Sec.2.(a) covers only actions that are “deceptive.” Indeed, many of the section’s prohibitions wouldn’t make sense without an exception for legitimate programs. Certainly users should be able to set new home pages if they choose, and when users install new programs, those programs should be able to add entries to browsers’ Favorites menus. Yet these same actions are unwanted when performed by spyware programs. Unfortunately, the bill offers no definition or clarification as to how to tell the difference — as to what constitutes a deceptive action. Is an action “deceptive” when it is disclosed only in fine print in a 25-page license? When the action is disclosed in a license users are never actually shown, only offered via an optional link? When the action is prominently disclosed, but in an installation performed by a site targeting children? Surprisingly, the bill is entirely silent on these important questions of what exactly Sec.2. does or does not prohibit. Instead the bill merely leaves these matters to FTC “guidance.”

Pending such FTC rules, the Sec.2. requirements will be largely ineffective: Spyware companies will claim that users consented to their schemes when users pressed “yes” in installation dialog boxes — no matter how lengthy, confusing, misleading, or poorly-presented the on-screen disclosures. At best, the bill asks the FTC to address the problems Sec.2. identifies — hardly the “tough” regulation Reuters reported. The FTC’s prior “consent” comments suggest that the FTC would consider a “yes” press as an absolute bar against a Sec.2. complaint. Since so many spyware programs install by tricking users into granting at least some form of supposed consent, this FTC interpretation would eviscerate Sec.2.

Sec.2. is also puzzling because many, if not most, of the specified practices are already prohibited by existing law. For example, Sec.2.(a)(5) prohibits “Inducing the owner or authorized user to install or execute computer software by misrepresenting the identity or authority of the person or entity providing the computer software to the owner or user” — which sounds like common law fraud, and is therefore already illegal. Similarly, Sec.2.(a)(8)’s prohibition on removing security software echoes the existing Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, which prohibits “exceed[ing] authorized access” to a computer.

Perhaps Sec.2. is valuable for providing a consolidated listing of prohibited practices pertaining to unwanted software, higher penalties for such practices, and renewed calls for enforcement. But the underlying unauthorized interference with users’ computers is already illegal. What Sec.2. could do — but doesn’t — is tighten notions of consent so that spyware companies can’t claim authorization, then escape liability, where users didn’t intend to grant authorization.

The Sec.3. Notice Requirements, and How Spyware Companies Can Abuse Them

The bill’s Sec.3.(c) gives some regulation of notice and consent as to programs that collect personal information, or that track online activities and show advertising. But the bill is exceptionally permissive, seeming to permit many of the tricks spyware companies have long used to persuade users to accept their software.

Sec.3. sets out four basic requirements for notice and consent:

- Notice must be “clearly distinguish[ed]” from other on-screen text. ((c)(1)(A))

- Notice must include text “substantially similar” to “This program will collect and transmit information about you” or “This program will collect information about Web pages you access and will use that information to display advertising on your computer.” ((c)(1)(B))

- Notice must remain on screen until the user grants or denies consent. ((c)(1)(C),(E))

- Notice must provide an option giving “clear” additional information about the type of information to be collected and the purpose of such collection. ((c)(1)(D))

Taken in the abstract, these sound like reasonable requirements. But many providers of unwanted software already largely satisfy these requirements, while nonetheless installing their software in ways that confuse users and in ways that don’t give users a full sense of what the programs will actually do.

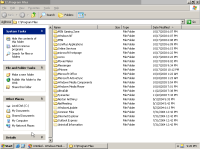

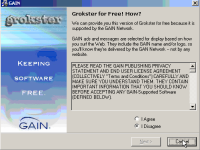

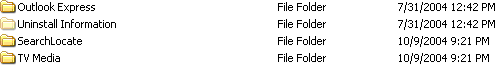

Consider, for example, the Grokster installation procedure.. By my count, Grokster shows a 120-page Claria license followed by a 278-page license for half a dozen other programs. These licenses differ somewhat from the specific text in the bill’s section (c)(1)(B), but the bill’s “substantially similar” provision means the existing text may be sufficient. And although Grokster ultimately installs at least fifteen different unwanted programs, it need only show a Sec.3. disclosure once: The fact that Claria’s disclosure (perhaps) satisfies Sec.3.’s requirements seems to clear the way, under the plain language of Sec.3., for Grokster to install whatever other programs it wants, without so much as telling users the names of the programs to be installed.

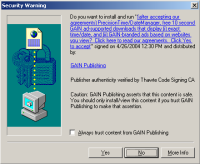

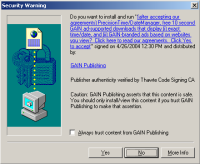

Even “drive-by downloads” might be taken to be permitted under the bill. Recall the ActiveX “security warnings” shown by Windows versions prior to XP Service Pack 2 — pop-ups like that shown at right, appearing when users browse unrelated web sites, but installing software on users’ computers with a single press of a “yes” button. (These practices are all the more confusing because some legitimate programs, like Macromedia Flash, use the same dialog box to install their latest versions.) Turning to the specific requirements of the bill as applied to these installation attempts:

Even “drive-by downloads” might be taken to be permitted under the bill. Recall the ActiveX “security warnings” shown by Windows versions prior to XP Service Pack 2 — pop-ups like that shown at right, appearing when users browse unrelated web sites, but installing software on users’ computers with a single press of a “yes” button. (These practices are all the more confusing because some legitimate programs, like Macromedia Flash, use the same dialog box to install their latest versions.) Turning to the specific requirements of the bill as applied to these installation attempts:

- The use of a hyperlink, with resulting blue highlighting and underlining, could be claimed to satisfy the “clearly distinguish” requirement of (c)(1)(A).

- Claria’s existing disclosure could be claimed to be “substantially similar” to the required (c)(1)(B) statement. Claria’s existing “display … GAIN-branded ads” disclosure could be claimed to be similar to the bill’s “display advertising on your computer” model text. Claria’s “based on websites you view” might be claimed to be similar to the bill’s “collect information about Web pages you access.”

- The installation dialog box remains on screen until the user makes a choice, seemingly satisfying the requirements in (c)(1)(E).

- Claria’s hyperlink provides more information, seemingly responsive to the requirement in (c)(1)(D), though Claria’s lengthy text might or might not satisfy the bill’s “clear description” requirement.

Of course, some practices are so egregious that even the proposed bill would prohibit them. For example, when 180solutions software is installed through security holes, users get no notice whatsoever and have no opportunity at all to deny consent — violating the Sec.3. requirements. But Claria’s drive-by downloads are also arguably unacceptable. Why should Congress endorse software installed via popups which appear as users browse totally unrelated content; which install software with just a single click of “yes”; and which look so similar to popups installing software that users actually need (like Macromedia Flash)?

I see at least three specific problems with Sec.3.:

- Allowing disclosures to be written in “substantially similar” language — inviting spyware providers to describe their products in marketing euphemisms, deterring users from making a impartial choice based on unbiased facts and plain language.

- Allowing installation of many unwanted programs after only a single disclosure — without telling users about the names or even the quantity of programs to be installed.

- Giving software providers carte blanche to repurpose users’ computers for software providers’ benefit, after requiring only a one-sentence pro forma disclosure.

Weak enforcement

Suppose some bad actor violated the bill’s requirements. How will they be held accountable? Sec.4. speaks to enforcement — unfortunately giving enforcement authority only to the FTC.

Experience shows the FTC to be slow to pursue spyware perpetrators: The FTC has filed only a single anti-spyware case to date, and has failed to act on (among scores of other problematic activities) the installation of dozens of programs through security holes, even when documented in research posted months ago (by me and others). If the FTC won’t rigorously enforce Bono’s bill, then the bill will be dead letter — on the books, but unsuccessful in constraining spyware companies’ behavior.

A better approach would encourage enforcement by parties with a strong incentive to act. State attorneys general face public election which inspires aggressive pro-consumer litigation. Private parties also have clear incentives to sue, since they could seek to recover damages from spyware companies operating in violation of the bill’s requirements. I’d like to see the enforcement clause broadened to grant enforcement powers to those with real incentives to identify and pursue wrongdoers.

Alternative legislation

What would tough anti-spyware legislation look like? One easy addition is to specifically prohibit drive-bys. Congress should not allow the installation, as users merely browse unrelated web pages, of software that tracks online activities and shows ads. Users should only be offered such software at a time and in a manner in which they can meaningfully evaluate the agreement. They should have to seek out such software to be installed on their computer; it should not be not be foisted upon them. Neither should users suffer repeat installation attempts — like reappearing “You must press ‘Yes’ to continue” popups that harass users until they agree. Saying ‘no’ once should be enough, but nowhere does the bill prevent spyware providers from asking over and over.

Tough anti-spyware legislation would also establish special barriers against practices known to be particularly detrimental to users’ PCs. Installing a dozen or more spyware programs cripples even a fast computer, and tough anti-spyware legislation would, at the least, require special disclosures when a requested program intends to install multiple other programs. I’d expect at least a listing of all the specific programs to be installed, with a one-sentence description of the effects and purported benefits of each.

Congress should also speak to the uses of affiliates to perform software installations. Companies like 180solutions have embraced affiliate installations — offering web-based signup procedures (not to mention spam email campaigns) to find “partners” to install 180 software in exchange for commissions of $0.07 per installation. Later, when 180 software is installed without notice or consent, 180 claims “deceptive distribution” — as if 180 were surprised that their unaccountable affiliates didn’t follow the rules. A tough anti-spyware law should decisively close this potential loophole. Where software developers are lax in their supervision of affiliates, and especially where affiliates’ bad practices continue for months on end, the software developers should be held accountable — legally and financially — for the prohibited actions of their affiliate business partners.

As discussed above, the bill lacks meaningful enforcement provisions. Real compliance almost certainly requires permitting enforcement by state attorney generals and private parties. A truly tough anti-spyware bill should also hold advertisers accountable for their decisions to contract with, support, and fund spyware companies. If an advertiser hires a spyware company to show its ads through software wrongly installed on users’ PCs, perhaps that advertiser should pay a share of the costs of repairing users’ computers.

Rather than helping the spyware problem, Bono’s weak bill could even make things worse. If passed, the bill will fill the space — making further federal anti-spyware legislation unlikely, at least in the short run. Also, the bill specifically supercedes state laws which might be tougher — so if Bono’s bill passes, no state can set higher requirements. (In a recent hearing, Congressman Gillmor raised this same concern.) Finally, passing a bill that rubber-stamps spyware firms’ controversial practices serves only to make those companies stronger. Claria publicly supported California’s toothless anti-spyware bill. Since Bono’s bill will do equally little to curb Claria’s practices, Claria will surely support this legislation too.

But all is not lost. With half a dozen line edits, Bono’s bill could be significantly better. And the bill is only a few hours of editing away from prohibiting spyware companies’ major deceptive practices without affecting legitimate practices used by mainstream companies. Here’s hoping for a bill that truly deserves the “tough” moniker.