I’ve previously written about two different ways that Google gets involved in distributing and funding spyware: Allowing Blogspot to be used to foist spyware through tricky ActiveX popups and paying fees to AdSense sites who in turn buy pop-ups through 180solutions (such that revenue ultimately flows from advertiser to Google to AdSense site to 180solutions).

Many of Blogspot’s ActiveX popups have disappeared since my February article, and Google promises to put a check on AdSense popups too. But Google’s role goes much further: Through syndication relationships, Google provides ads to multiple web toolbar operators, including to toolbars installed on users’ PCs without notice or consent. Google pays these toolbar companies for the ads they show — thereby supporting and funding their operations.

Google’s Rules and Policies

Google repeatedly tells its advertisers that their ads will appear only on Google’s “high-quality” partner sites.

What does “high-quality” mean? Google doesn’t say. But last year Google published a set of “Software Principles” for advertising programs — calling for improved notice and consent before advertising software becomes installed. A basic notion of “high-quality” sites is that they don’t solicit traffic through software violating Google’s Software Principles, and that they also don’t make or distribute such software. My sense is that an advertising channel cannot be considered “high-quality” if it is predicated on installing software onto users’ PCs without their consent or without their informed consent.

Ask Jeeves and Its Ill-Gotten Toolbars

I’ve previously shown that Ask Jeeves’ toolbars sometimes install without asking for permission (additional videos on file). Other Jeeves toolbars install in effective stealth or otherwise without informed consent. Some examples:

- The AJ toolbar bundled with the iMesh P2P program is disclosed only at page 27 of iMesh’s 56 page license. Users who manage to locate this paragraph are likely to face some difficulty in understanding it; the text largely uses euphemisms in place of the word “toolbar” to describe AJ’s software. (Until recently, the license didn’t use the word “toolbar” at all.) See also analysis by SearchEngineWatch.

- Kazaa has long bundled AJ’s MySearch toolbar (though a recent revision to Kazaa seems to have replaced it with a competing toolbar). Historically, AJ’s inclusion has been prominently disclosed in the Kazaa installer. But users wanting to learn more about AJ have had no reasonable way to find details or even to read AJ’s license: Kazaa oddly placed the AJ license agreement at page 32 of a document puzzlingly labeled “Altnet License Agreement” (without mention of AJ).

- When Ask Jeeves promotes its toolbars in banner advertising, it again fails to obtain the kind of consent that Google seeks. AJ advertises on kids sites, using euphemisms in place of plain language, and showing pictures of smiley faces rather than pictures of its advertising toolbar. AJ’s installation does not affirmatively show a license agreement providing more detailed terms. On 800×600 screens (such as many older PCs), AJ even fails to show a properly-labeled link to a license or to mention the word “toolbar” in on-screen text prior to installation..

So even if a user has an AJ toolbar, the user may not want it, may not know how it arrived, and may not have granted meaningful consent (if any consent at all). These various behaviors seem to constitute multiple violations of Google’s Software Principles — among others, installation without any consent at all, as well as failure to provide appropriate “upfront disclosure.”

PPC advertisers

money

viewers

viewers

Google AdWords

money

viewers

viewers

Ask Jeeves

How Funds flow from advertisers to Ask Jeeves

Notwithstanding the tricky installation methods used by these Ask Jeeves toolbars, AJ’s revenues ultimately largely come from Google: Enter a search term into an AJ toolbar, and most of the resulting ads are Google AdWords ads. AJ’s recent 10-Q says AJ gets 74% of its total revenues from Google. With AJ’s 2005 Q1 revenue at $94.9 million, Google apparently pays AJ approximately $278 million per year. Fees flow from advertiser to Google to AJ, as shown at right.

Google’s relationship with Ask Jeeves is widely publicized: Google issued a press release announcing its relationship with AJ, and Google’s main AdWords page even shows AJ’s logo. But Google’s statements to advertisers fail to mention the possibility that AJ will send advertisers traffic that was obtained from toolbars installed without proper notice and consent or, in some instances, any notice or consent at all.

Of course, Google’s relationships with toolbar makers doesn’t stop with Ask Jeeves. Google ads end up shown through other distribution channels with even worse installation practices.

How Google Supports IBIS WebSearch

I’ve long watched the IBIS WebSearch toolbar and its troubled installation practices. I’ve often seen IBIS installed through security holes with no notice or consent. (Multiple additional videos on file.) I’ve also posted documentation of IBIS installed in tricky bundles with minimal notice. I’ve even seen IBIS offered in repeated ActiveX popups that tell users “you must click yes to continue” if users initially refuse installation. Other IBIS ActiveX popups offer a defective license link; clicking the license yields no license. (Video proof on file.)

These practices seem to violate almost every one of Google’s Software Principles. Google says to let users decline an unwanted installation, to give users upfront disclosure of major program functions, to clearly disclose changes to browser configuration, and only to come bundled with other programs meeting these rules. But my records show IBIS failing to meet each of these requirements.

PPC advertisers

money

viewers

viewers

Google AdWords

money

viewers

viewers

Go2Net

money

viewers

viewers

IBIS WebSearch

How Funds flow from advertisers to IBIS WebSearch

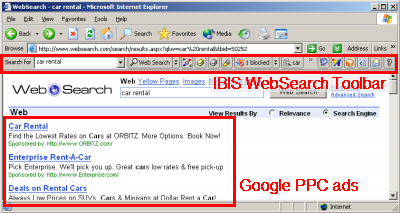

Notwithstanding these apparent violations of Google’s Software Principles, IBIS shows many Google ads, seemingly receiving payment for such displays. Run a search in IBIS, and the ads often match Google ads. See screenshot at left. See also a video showing a search conducted through the IBIS WebSearch toolbar, a click on an ad, and the immediate creation of Go2Net and Google cookies. (Note that Google ads typically fill the entire screen of an 800×600 web browser.)

Click on a WebSearch ad, and traffic flows from WebSearch to Go2Net to Google to advertiser. Payment flows in the opposite direction. See diagram at right.

Using a network monitor (“packet sniffer”), I recorded the raw traffic that occurred when I clicked on the Orbitz ad shown above. In particular, my browser retrieved the URLs listed below. See also the full packet log of the associated transmissions, showing the full parameters of all redirects.

http://www.websearch.com/xfb_redir.aspx?CP=…

http://clickit.go2net.com/search?pos=1&ppos=1&plnks=5…&query=car+rental…

http://clickit.go2net.com/search/id?pos=1&ppos=1&plnks=5…&query=car+rental

http://www.google.com/url?sa=l&q=http://www.orbitz.com/App/DisplayCarSearch…&ai=…

http://www.google.com/url?q=http://www.orbitz.com/…&ai=…

http://www.orbitz.com/App/DisplayCarSearch?semsource=goog&semkeyword=car+rental

Google’s listing of ad partners confirms that Google ads can be shown by InfoSpace, owner of Go2Net. Note that InfoSpace is a publicly-traded company (NASDAQ: INSP).

The example above shows an Orbitz ad being shown by IBIS WebSearch. In my testing, Orbitz often advertises through programs often called spyware. (Examples: Orbitz ads shown by Claria/Gator, eXact Advertising and Hotbar.) But because IBIS WebSearch syndicates and shows many Google ads for many keywords, IBIS shows ads even for advertisers who otherwise refuse to do business with spyware firms. Indeed, thanks to syndication from Google, IBIS even shows (and receives payment for showing) ads from firms that have filed suit against makers of such software. For example, I have captured proof of IBIS showing Google AdWords ads from the Hertz, LL Bean, and the New York Times, each of which has taken a stand against unwanted advertising software by suing Claria.

Enforcement Challenges

Google’s Software Principles document concludes by noting that “Responsible … advertisers can work to prevent [undesirable software] by avoiding these types of business relationships [those violating the principles set out above], even if … through intermediaries.” This is surely good advice. But Google’s far-reaching relationships with Ask Jeeves, IBIS, and others indicate that Google’s actions fall short of Google’s own recommendations to others.

Most of Google’s AdWords partners are probably highly trustworthy — unlikely to show ads except in the ways that Google intends and permits. But where Google’s partners have partners of their own (as InfoSpace/Go2Net does in WebSearch), enforcement is likely to be more difficult and accountability lacking. Google could eliminate this problem by prohibiting its partners from syndicating Google ads on to further partners of their own — though such a rule would narrow the network showing Google sites and thereby reduce Google’s revenues. Google’s existing partners may also have contractual rights to distribute Google ads to partners; AJ’s 10-Q comments that AJ “display[s] paid listings from Google on … many of the third-party sites in our network” (page 18).

My testing of Go2Net/WebSearch was made particularly difficult by the fact that the Google ads at issue apparently occur only on nights and weekends. During the business day, I have observed that WebSearch generally shows ads from other sources, not from Google. This type of change tends to undermine and confuse casual efforts at testing and enforcement.

Tough enforcement is particularly difficult due to the large amount of money at issue. Ask Jeeves’ relationship with Google has grown to hundreds of millions of dollars per year. Yet my documentation of AJ’s installation practices demonstrates that some AJ traffic to Google comes from AJ toolbars installed without consent or installed without consent that meets Google’s standards. With huge money on the line, will Google terminate its relationship with AJ, as its Principles seem to require (“avoid… these types of business relationships”)? The wrongful installations cannot immediately be undone — it’s hard (though probably not impossible) to determine exactly which AJ toolbar installations lacked consent or lacked the kind of consent Google calls for. But it seems clear that AJ’s practices don’t live up to Google’s standards. What will Google do now?

SiteAdvisor markup of search results, flagging a representative Google ad — asking users to pay for software widely available elsewhere for free.

SiteAdvisor markup of search results, flagging a representative Google ad — asking users to pay for software widely available elsewhere for free.

IBIS WebSearch results showing Google PPC ads

IBIS WebSearch results showing Google PPC ads