For consumers, it’s easy to applaud Uber, Lyft, and kin (transportation network companies or TNCs). Faster service, usually more reliable, often in nicer vehicles—all at lower prices. What’s to dislike?

Look behind the curtain and things are not so clear. TNCs cut corners on issues from insurance to inspections to background checks, thereby pushing costs from their customers to the general public—while also delivering a service that plausibly falls short of generally-applicable requirements duly established by law and, sometimes, their own marketing promises.

In a forthcoming article in Competition Policy International, Whither Uber?: Competitive Dynamics in Transportation Networks, I look at a range of concerns in this area, focusing on market dynamics and enforcement practices that have invited TNC to play fast-and-loose. This page offers excerpts and some further thoughts.

Corners cut

My article enumerates a variety of concerns resulting from prevailing TNC practices:

In most jurisdictions, a "for hire" livery driver needs a commercial driver’s license, a background check and criminal records check, and a vehicle with commercial plates, which often means a more detailed and/or more frequent inspection. Using ordinary drivers in noncommercial vehicles, TNCs skip most of these requirements, and where they take such steps (such as some efforts towards a background check), they do importantly less than what is required for other commercial drivers (as discussed further below). One might reasonably ask whether the standard commercial requirements in fact increase safety or advance other important policy objectives. On one hand, detailed and frequent vehicle inspections seem bound to help, and seem reasonable for vehicles in more frequent use. TNCs typically counter that such requirements are unduly burdensome, especially for casual drivers who may provide just a few hours of commercial activity per month. Nonetheless, applicable legal rules offer no "de minimis" exception and little support for TNCs’ position.

Differing standards for background checks raise similar questions. TNCs typically use standard commercial background check services which suffer from predictable weaknesses. For one, TNC verifications are predicated on a prospective driver submitting his correct name and verification details, but drivers with poor records have every incentive to use a friend’s information. (Online instructions tell drivers how to do it.) In contrast, other commercial drivers are typically subject to fingerprint verification. Furthermore, TNC verifications typically only check for recent violations—a technique far less comprehensive than the law allows. (For example, Uber admits checking only convictions within the last seven years, which the company claims is the maximum duration permitted by law. But federal law has no such limitation, and California law allows reporting of any crime for which release or parole was at most seven years earlier.) In People of the State of California v. Uber, these concerns were revealed to be more than speculative, including 25 different Uber drivers who passed Uber’s verifications but would have failed the more comprehensive checks permitted by law.

Relatedly, TNC representations to consumers at best gloss over potential risks, but in some areas appear to misstate what the company does and what assurances it can provide. For example, Uber claimed its service offered "best in class safety and accountability" and "the safest rides on the road" which "far exceed

what’s expected of taxis"—but taxis, with fingerprint verification of driver identity, offer improved assurances that the person being verified is the same person whose information is checked. Moreover, Uber has claimed to be "working diligently to ensure we’re doing everything we can to make Uber the safest experience on the road" at the same time that the company lobbies against legislation requiring greater verifications and higher safety standards.

Passengers with disabilities offer additional complaints about TNCs. Under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and many state laws, passengers with disabilities are broadly entitled to use transportation services, and passengers cannot be denied transport on the basis of disability. Yet myriad disabled passengers report being denied transport by TNCs. Blind passengers traveling with guide dogs repeatedly report that TNC drivers sometimes reject them. In litigation Uber argued that its service falls beyond the scope of the ADA and thus need not serve passengers with disabilities, an argument that a federal court promptly rejected. Nonetheless, as of November 2015, Uber’s "Drivers" page continues to tell drivers they can "choose who you pick up," with no mention of ADA obligations, nor of prohibitions on discrimination on the basis of race, gender, or other prohibited factors.

I offer my sharpest criticism for certain TNC practices as to insurance:

TNCs encourage drivers to carry personal insurance rather than commercial insurance —anticipating, no doubt correctly, that drivers might be put off by the higher cost of commercial coverage. But TNC drivers are likely to have more frequent and more costly accidents than ordinary drivers: they drive more often, longer distances, with passengers, in unfamiliar locations, primarily in congested areas, and while using mobile apps. To the extent that drivers make claims on their personal insurance, they distort the market in two different ways: First, they push up premiums for other drivers. Second, the cost of their TNC accidents are not borne by TNC customers; by pushing the cost to drivers in general, TNCs appear to be cheaper than they really are.

In a notable twist, certain TNC policies not only encourage drivers to make claims on their personal policies, but further encourage drivers to commit insurance fraud. Consider a driver who has an accident during the so-called "period 1" in which the driver is running a TNC app, but no passenger has yet requested a ride from the driver. If the driver gets into an accident in this period, TNCs historically would deny both liability and collision coverage, claiming the driver was not yet providing service through the TNC. An affected driver might instead claim from his personal insurance, but if the driver admits that he was acting as a TNC driver—he had left home only to provide TNC services; he had transported several passengers already; he was planning more—the insurer will deny his claim. In fact, in all likelihood, an insurer in that situation would drop the driver’s coverage, and the driver would also be unable to get replacement coverage since any new insurer would learn the reason for the drop. As a practical matter, the driver’s only choices are to forego insurance coverage (a possibility in case of a collision claim, though more difficult after injuring others or damaging others’ property) or, more likely, lie to his insurance issuer. California law AB 2293, effective July 1, 2015, ended this problem as to collision claims in that state, requiring TNCs to provide liability coverage during period 1, but offering nothing elsewhere, nor any assistance on collision claims.

Where TNC practices merely shortchange a company’s own customers, such as providing a level of safety less than customers were led to believe, we might hope that market forces would eventually fix the problem—informing consumers of the benefits they are actually receiving, or compelling TNCs to live up to their promises. But where TNC practices push costs onto third parties, such as raising insurance rates for all drivers, there is no reason to expect market forces to suffice. Regulatory enforcement, discussed below, is the only apparent way forward on such issues.

Competitive dynamics when enforcement is lax

A striking development is the incompleteness of regulation of TNC or, more precisely, the incompleteness of enforcement of existing and plainly-applicable regulation. I explain:

In this environment, competition reflects unusual incentives: Rather than competing on lawful activities permitted under the applicable regulatory environment, TNC operators compete in part to defy the law—to provide a service that, to be sure, passengers want to receive and buyers want to provide, notwithstanding the legal requirements to the contrary.

The brief history of TNCs is instructive. Though Uber today leads the casual driving platforms, it was competing transportation platform Lyft that first invited drivers to provide transportation through their personal vehicles. Initially, Uber only provided service via black cars that were properly licensed, insured, and permitted for that purpose. In an April 2013 posting by CEO Travis Kalanick, Uber summarized the situation, effectively recognizing that competitors’ casual drivers are largely unlawful, calling competitors’ approach "quite aggressive" and "non-licensed." (Note: After I posted this article, Uber removed that document from its site. But Archive.org kept a copy. I also preserved a screenshot of the first screen of the document, a PDF of the full document, and a print-friendly PDF of the full document.)

Uber’s ultimate decision, to recognize Lyft’s approach as unlawful but nonetheless to follow that same approach, is hard to praise on either substantive or procedural grounds. On substance, it ignores the important externalities discussed above—including safety concerns that sometimes culminate in grave physical injury and, indeed, death. On procedure, it defies the democratic process, ignoring the authority of democratic institutions to impose the will of the majority. Uber has all but styled itself as a modern Rosa Parks defying unjust laws for everyone’s benefit. But Uber challenges purely commercial regulation of business activity, a context where civil disobedience is less likely to resonate. And in a world where anyone dissatisfied with a law can simply ignore it, who’s to say that Uber is on the side of the angels? One might equally remember former Arkansas governor Orville Faubus’ 1957 refusal to desegregate public schools despite a court order.

Notice the impact on competition: Competitors effectively must match Uber’s approach, including ignoring applicable laws and regulation, or suffer a perpetual cost disadvantage.

Consider Hailo’s 2013-2014 attempt to provide taxi-dispatch service in New York City. On paper, Hailo had every advantage: $100 million of funding from A-list investors, a strong track record in the UK, licensed and insured vehicles, and full compliance with every applicable law and regulation. But Uber’s "casual driver" model offered a perpetual cost advantage, and in October 2014 Hailo abandoned the U.S. market. Uber’s lesson to Hailo: Complying with the law is bad business if your competitor doesn’t have to. Facing Uber’s assault in numerous markets in Southeast Asia, transportation app GrabTaxi abandoned its roots providing only lawful commercial vehicles, and began "GrabCar" with casual drivers whose legality is disputed. One can hardly blame them—the alternative is Hailo-style irrelevance. When Uber ignores applicable laws and regulators stand by the wayside, competitors are effectively compelled to follow.

Moreover, the firm that prevails in this type of competition may build a corporate character that creates other problems for consumers and further burdens on the legal system. My assessment:

Notice Uber’s recent scandals: Threatening to hire researchers to "dig up dirt" on reporters who were critical of the company. A "God view" that let Uber staff see any rider’s activity at any time without a bona fide purpose. Analyzing passengers’ rides to and from unfamiliar overnight locations to chronicle and tabulate one-night-stands. Charging passengers a "Logan Massport Surcharge & Toll" for a journey where no such fee was paid, or was even required. A promotion promising service by scantily-clad female drivers. The CEO bragging about his business success yielding frequent sexual exploits. "Knowing and intentional" "obstructive" "recalcitrance" in its "blatant," "egregious," "defiant refusal" to produce documents and records when so ordered by administrative law judges.

On one view, these are the unfortunate mishaps of a fast-growing company. But arguably it’s actually something more than that. Rare is the company that can pull off Uber’s strategy—fighting regulators and regulation in scores of markets in parallel, flouting decades of regulation and managing to push past so many legal impediments. Any company attempting this strategy necessarily establishes a corporate culture grounded in a certain disdain for the law. Perhaps some laws are ill-advised and should be revisited. But it may be unrealistic to expect a company to train employees to recognize which laws should be ignored versus which must be followed. Once a company establishes a corporate culture premised on ignoring the law, its employees may feel empowered to ignore many or most laws, not just the (perhaps) outdated laws genuinely impeding its launch. That is the beast we create when we admit a corporate culture grounded in, to put it generously, regulatory arbitrage.

An alternative model

Uber offers one approach to regulation: Ignore any laws the company considers outdated or ill-advised. But in other sectors, firms have chosen a different model to demonstrate their benefits and push for regulatory change. I offer one example as to the launch of Southwest Airilnes:

Planning early low-fare operations in 1967, Southwest leaders realized that the comprehensive regulatory scheme, imposed by the federal Civil Aeronautics Board, required unduly high prices, while simultaneously limiting routes and service in ways that, in Southwest’s view, harmed consumers. Envisioning a world of low-fare transport, Southwest sought to serve routes and schedules CAB would never approve, at prices well below what regulation required.

Had Southwest simply begun its desired service at its desired price, it would have faced immediate company-ending sanctions; though CAB’s rules were increasingly seen as overbearing and ill-advised, CAB would not have allowed an airline to brazenly defy the law. Instead, Southwest managers had to find a way to square its approach with CAB rules. To the company’s credit, they were able to do so. In particular, by providing solely intra-state transport within Texas, Southwest was not subject to CAB rules, letting the company serve whatever routes it chose, at the prices it thought best. Moreover, these advantages predictably lasted beyond the impending end of regulation: After honing its operations in the intra-state Texas market, Southwest was well positioned for future expansion.

In fact Southwest is far from unique in its attention to regulatory matters. Consider the recent experience of AT&T. In October 2015, AT&T sought to offer wifi calling for certain smartphones, but the company noticed that FCC rules required a teletypewriter (TTY) service for deaf users, whereas AT&T envisioned a replacement called real-time text (RTT). Competitors Sprint and T-Mobile pushed ahead without TTY, not bothering to address the unambiguous regulatory shortfall. To AT&T’s credit, it urged the FCC to promptly approve its alternative approach, noting the "asymmetry in the application of federal regulation to AT&T on the one hand and its marketplace competitors on the other hand." With the issue framed so clearly, FCC leaders saw the need for action, and they did so just days after AT&T’s urgent request.

Knowing that its casual-driver service was unlawful, as effectively admitted in CEO Travis Kalanick’s April 2013 posting Uber could have sought a different approach. (Note: After I posted this article, Uber removed that document from its site. But Archive.org kept a copy. I also preserved a screenshot of the first screen of the document, a PDF of the full document, and a print-friendly PDF of the full document.) I argue that this approach might have worked:

Assuming strict compliance with the law, how might Uber have tried to get its service off the ground? One possibility: Uber could have sought some jurisdiction willing to let the company demonstrate its approach. Consider a municipality with little taxi service or deeply unsatisfactory service, where regulators and legislators would be so desperate for the improvements Uber promised that they would be willing to amend laws to match Uber’s request. Uber need not have sought permanent permission; with great confidence in its offering, even a temporary waiver might have sufficed, as Uber would have anticipated the change becoming permanent once its model took off. Perhaps Uber’s service would have been a huge hit—inspiring other cities to copy the regulatory changes to attract Uber. Indeed, Uber could have flipped the story to make municipalities want its offering, just as cities today vie for Google Fiber and, indeed, make far-reaching commitments to attract that service.

Where’s the enforcement?

Park in front of a fire hydrant, and you can be pretty sure that you’ll get a ticket—even if there’s no fire and even if no one is harmed. TNCs violate laws that are often equally unambiguous, yet often avoid sanction. I discuss Uber’s standard approach to unfavorable regulation:

[Regulators’ findings of unlawfulness] are not self-effectuating, even when backed up with cease and desist letters, notices of violation, or the like. In fact, Uber’s standard response to such notices is to continue operation. Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission prosecutor Michael Swindler summarized his surprise at Uber’s approach: "In my two-plus decades in practice, I have never seen this level of blatant defiance," noting that Uber continued to operate in despite an unambiguous cease-and-desist order. Pennsylvania Administrative Law Judges were convinced, in November 2015 imposing $49 million of civil penalties, electing to impose "the maximum penalty" because Uber flouted the cease-and-desist order in a "deliberate and calculated" "business decision."

Nor was this defiance limited to Pennsylvania. Uber similarly continued to provide service at San Francisco International Airport, and affirmatively told passengers "you can request" an Uber at SFO, even after signing a 2013 agreement with the California Public Utilities Commission disallowing transport onto airport property unless the airport granted permission and even after San Francisco International Airport served Uber with a cease-and-desist letter noting the lack of such permission. In some instances, cities ultimately force Uber to cease or suspend operations. But experience in Paris is instructive. There, Uber continued operation despite a series of judicial and police interventions. Only the arrest of two Uber executives compelled the company to suspend its casual driving service in Paris.

While TNCs continue operation in most jurisdictions where they have begun, they nonetheless face a growing onslaught of litigation. PlainSite indexes 77 different dockets involving Uber, including complaints from competitors, regulators, drivers and passengers. (Notably, this is only a small portion of the disputes, omitting all international matters, most state proceedings, and most or all local and regulatory proceedings.) But no decision has gone as far as the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission docket culminating in the remarkable 57-page November 2015 decision by two administrative law judges. In a July 1, 2014 order, the judges had ordered Uber to cease and desist its UberX service throughout the state for lack of required permits. Uber refused. The judges eviscerate Uber’s response, noting that their prior order "clearly directed Uber to cease its ridesharing service until it received authority from the ion," and "Uber was acting in defiance … as a calculated business decision" because "Uber simply did not want to comply … so it continued to operate." Uber then argued that it was justified in continuing to operate because the July 1, 2014 order was subject to further review and appeal. The PUC judges call this argument "incredibl[e]," noting the lack of any legal basis for Uber to refuse to comply with a duly issued order. It’s hard to imagine a decision more thoroughly rejecting Uber’s conduct in this period.

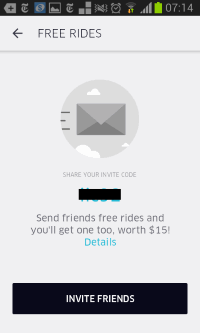

Notably, the Pennsylvania PUC fully engages with Uber’s defenses. In this proceeding and elsewhere, Uber argued that it is "just a software company" and hence not subject to longstanding laws that regulate transportation providers. The PUC picks apart this argument with care, noting Uber’s extensive control over the system. The PUC notes relevant facts demonstrating Uber’s "active role": Uber screened drivers and ejected some. Uber initially required drivers to use company-owned smartphones. Uber offered and touted an insurance policy which it claimed would cover possible accidents. Uber held the service out to the public as "Uber," including emails subject lines like "Your first Uber ride" and "Your ride with Uber" as well as message text like "Uber invite code" and "thanks for choosing Uber," all of which indicate a service that is Uber, with the company providing a full service, not just software. Uber further charges customer credit cards, using a charge descriptor solely referencing Uber. Not mentioned by PUC but equally relevant, Uber attracted both drivers and passengers with subsidies and price adjustments, set compulsory prices that neither side could vary, published drivers whose conduct fell short of Uber’s requirements, and mediated disputes between passengers and drivers. The PUC notes the breadth of conduct requiring license authority: "offering, or undertaking, directly or indirectly, service for compensation to the public for the transportation of passengers" (emphasis added). If the word "indirect" is to have any meaning in this statute, how could it not include Uber?

The PUC imposed a $49 million civil penalty against Uber for its intentional operation in violation of a PUC order. The PUC discussed the purpose of this penalty: "not just to deter Uber, but also [to deter] other entities who may wish to launch … without Commission approval." Their rationale is compelling: If the legal system requires a permit for Uber’s activity, and if we are to retain that requirement, sizable penalties are required to reestablish the expectation that following the law is indeed compulsory.

Meanwhile, the PUC sets a benchmark for others. Uber flouted a PUC order in Pennsylvania from July 1, 2014 through August 21, 2014. In how many other cities, states, and countries do Uber and Lyft equally violate the law? If each such jurisdiction imposed a similar fine, the total could well reach the billions of dollars—enough to put a dent in even Uber’s sizable balance sheet, and enough to compel future firms to rethink the way they approach law and regulation.

Looking back and looking ahead

Tempting as it may be to think Uber is first of its kind, others have tried this strategy before. I explain:

Take a walk down memory lane for a game of "name that company." At an entrepreneurial California startup, modern electronic communication systems brought speed and cost savings to a sector that had been slow to adopt new technology. Consumers quickly embraced the company’s new approach, particularly thanks to a major price advantage compared to incumbents’ offerings, as well as higher quality service, faster service, and the avoidance of unwanted impediments and frictions. Incumbents complained that the entrant cut corners and didn’t comply with applicable legal requirements. The entrant knew about the problems but wanted to proceed at full speed in order to serve as many customers as possible, as quickly as possible, both to expand the market and to defend against potential competition. When challenged, the entrant styled its behavior as "sharing" and said this was the new world order.

You might think I’m talking about Uber, and indeed these statements all apply squarely to Uber. But the statements fit just as well with Napster, the "music sharing" service that, during brief operation from 1999 to 2001, transformed the music business like nothing before or since. And we must not understate the benefits Napster brought: It offered convenient music with no need to drive to the record store, a celestial jukebox unconstrained by retail inventory, track-by-track choice unencumbered by any requirement to buy the rest of the album, and mobile-friendly MP3’s without slow "ripping" from a CD.

In fact, copyright litigation soon brought an end to Napster, including Chapter 7 bankruptcy, liquidation of the company’s assets, and zero return to investors. Where does that leave us?

One might worry that Napster’s demise could set society back a decade in technological progress. But subsequent offerings quickly found legal ways to implement Napster’s advances. Consider iTunes, Amazon Music, and Spotify, among so many others.

In fact, the main impact of Napster’s cessation was to clear the way for legal competitors—to increase the likelihood that consumers might pay a negotiated price for music rather than take it for free. When Napster offered easy free music with a major price advantage from foregoing payments to rights-holders, no competitor had a chance. Only the end of Napster let legitimate services take hold.

And what of Napster’s investors? We all now benefit from the company’s innovations, yet investors got nothing for the risk they took. But perhaps that’s the right result: Napster’s major innovations were arguably insufficient to outweigh the obvious and intentional illegalities.

I conclude the comparison:

Uber CEO Travis Kalanick knows the Napster story all too well. Beginning in 1998, he ran a file-sharing service soon sued by the MPAA and RIAA on claims of copyright infringement. Scour entered bankruptcy in response, giving Travis a first-hand view of the impact of flouting the law. Uber today has its share of fans, including many who would never have dared to run Napster. Yet the parallels are deep.

Despite the many concerns raised by TNC practices, I am fundamentally optimistic about the TNC approach:

It is inconceivable that the taxis of 2025 will look like taxis of 2005. Uber has capably demonstrated the benefits of electronic dispatch and electronic record-keeping, and society would be crazy to reject these valuable innovations. But Uber’s efforts don’t guarantee the $50+ billion valuation the company now anticipates—and indeed, the company’s aggressive methods seem to create massive liability for intentional violations in most jurisdictions where Uber operates. If applicable regulators, competitors, and consumers succeed in litigation efforts, they could well bankrupt Uber, arguably rightly so. But as with Napster’s indisputable effect on the music industry, Uber’s core contributions are unstoppable and irreversible. Consumers in the coming decades will no more telephone a taxi dispatcher than buy a $16.99 compact disc at Tower Records. And that much is surely for the best.

Will it be Uber (and perhaps Lyft) that bring us there? Or will their legal violations force a shut down, like Napster before them, to make way for lawful competitors? That, to my eye, is the multi-billion-dollar question.