Initial Zango Banner Ad

Zango ActiveX Prompt

Zango "Welcome" Screen

|

Zango Practices Violating Zango's Recent Settlement with the FTC I present and critique current installation and operation practices of Zango, focusing on practices violating Zango's recent settlement with the FTC. |

Related Projects 180solutions & Affiliate Commissions WhenU Violates Own Privacy Policy |

In my hands-on testing, Zango continues numerous practices likely to confuse, deceive, or otherwise harm typical users as well as practices specifically contrary to Zango's obligations under its November 2006 settlement with the FTC.

Among these practices are widespread, ongoing Zango-designed installation sequences which install Zango pop-up ad software without any on-screen disclosure of material terms. Instead, these installations mention Zango's effects only in a lengthy EULA – exactly contrary to the FTC settlement's requirements.

Zango's ongoing practices also include widespread in-toolbar ads without the labeling and hyperlinks specifically required under the FTC settlement. Other Zango ads, including desktop icons and even certain pop-ups, also lack these labels and links.

This article summarizes selected incidents I have recently observed. In particular:

These practices call into question the integrity of Zango's business, as well as the status of Zango's compliance with its obligations under its recent settlement with the FTC.

Widespread Zango "ActiveX" Installations without Unavoidable, Prominent Disclosure of Material Terms (XP SP1 and Earlier)

In my recent and ongoing testing, Zango continues to purchase widespread banner advertisements that attempt to install Zango software through an ActiveX package, without unavoidable and prominent disclosure of material terms. These installations are likely to cause users to receive Zango software without fairly or fully understanding the true consequences of such installations.

These installations are shown to users running Windows XP Service Pack 1 and earlier versions of Windows. For Zango's treatment of XP SP2 users, see Widespread Zango Banner-Based Installations without Unavoidable, Prominent Disclosure of Material Terms (XP SP2) (below).

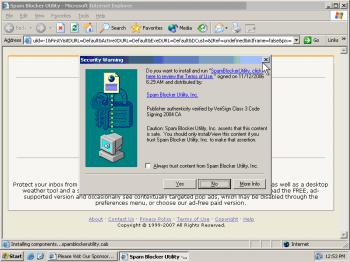

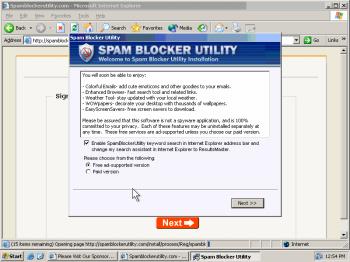

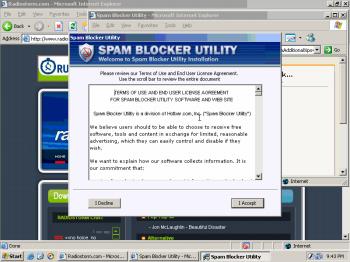

The screenshots at right show a representative Zango ActiveX installation, as observed on July 5, 2007. Installation proceeds in three steps:

1) These installations begin with a screen like that shown in the top screenshot at right – a Zango ad embedded within a third-party publisher's web site (here, ExitExchange). Zango makes an appealing opening offer -- in this case, “Do you want to block spam?” In some instances, these installations begin with a Zango ad appearing in a freestanding popup (as shown in the first screenshot in the subsequent section).

2) If a user clicks the Zango ad in step 1, the user is taken to an ActiveX dialog box like that shown in the second screenshot at right, asking the user to confirm installation. The dialog box features grammatically incoherent text (a run-on sentence without appropriate end-of-sentence punctuation), along with a hyperlink that optionally lets a user “review the Terms of Use.” Although a user can select that hyperlink to learn more about Zango's offer, users need not do so. Instead, users can simply press the “Yes” button to proceed with installation. In my experience, users receiving these ActiveX pop-ups often do just press “Yes”: Users have seen near-identical dialog boxes elsewhere (e.g. to install or update the widely-used and well-regarded Macromedia Flash player), and users fail to realize that, in this specific instance, the ActiveX box seeks to install advertising software with important productivity and privacy consequences.

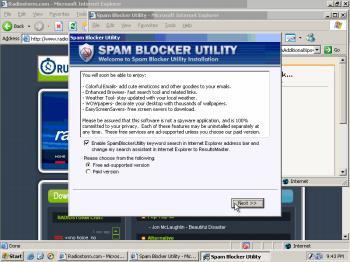

3) If the user presses OK in step 2, the receives the “Welcome” screen shown in the third screenshot at right. Here, Zango asks the user to choose between the “Free ad-supported version” and the “Paid version.” Despite these supposed options, users confront an unpalatable choice. A paid service is unlikely to be of interest, since users had never previously been warned of any fees. (Indeed, the “Paid version” option does not even mention the specific fee users would face – making that option all the less attractive.) But neither are users likely to reasonably expect to receive ads in association with the promised spam-stopping feature; this screen's reference to “ads” is Zango's first on-screen mention of advertisements. Crucially, the screen offers no way clear way for users to exit the installer: For a user who wants neither a paid service nor any “ads,” the screen lacks any “Cancel,” “Decline,” or “Abort” function, and the screen also lacks the “X” typically available in a Windows program's upper-right corner. Users are therefore effectively forced to choose between unwanted ads and an even less palatable out-of-pocket expenditure.

If a user chooses the “ad-supported” option in step 3, the user immediately receives Zango software – without any further opportunity to cancel installation. The Zango installation includes the “Hotbar” browser toolbar as well as the standard Zango software that tracks users' web browsing and searches, and shows pop-up ads.

Zango's ActiveX installation sequence does not fairly inform users of the key effects of installing Zango's software. The on-screen text makes no mention that ads will appear in pop-ups, an advertising format users are known to dislike. Neither does the on-screen text mention the important privacy consequences of installing Zango's software. Zango's only on-screen mention of “ads” is that one solitary word, appearing within the "Welcome" screen that gives users no clear ability to cancel installation.

Analysis of Zango's ActiveX Installation Sequence vis-à-vis Zango's FTC Settlement Obligations

This Zango ActiveX installation falls short of Zango's obligations under its recent settlement with the FTC.

Settlement Agreement III requires Zango to obtain “express consent” before installing any software program onto users' computers. The settlement agreement defines “express consent” as follows:

“Express consent” shall mean that, prior to downloading or installing any software program or application to consumers' computers: (a) Respondents clearly and prominently disclose the material terms of such software program or application prior to the display of, and separate from, any final End User License Agreement; and (b) consumers indicate assent to download or install such software program or application by clicking on a button that is labeled to convey that it will activate the download or installation, or by taking a substantially similar action.

The settlement defines “clear[] and prominent[]” disclosures to be only those that are “unavoidable” (among other requirements).

The material terms of Zango's software include 1) that it shows pop-up ads and 2) that it tracks users' browsing and searching. But Zango's ActiveX installation sequence discloses neither of these effects in the “clear[] and prominent[]” fashion the settlement requires. Rather, these effects are disclosed only if users click the hyperlink shown in the second screenshot above, whereas Zango's FTC settlement specifically requires that such disclosures be “unavoidable.”

The background screen in the second screenshot also does not disclose Zango's material terms with the requisite clarity or prominence. For one, the relevant disclosures are substantially covered by Zango's own ActiveX pop-up. Notice the screen layout, captured just as the installation sequence appears by default on a standard 800x600 screen. This default arrangement shows only a set of nonsensical sentence fragments (“Protect your inbox from ___ as well as a desktop weather tool and a s___ ad the FREE, ad___,” etc., s.i.c.), but not a single full sentence. These incoherent fragments certainly are not a “clear” statement of Zango's material effects. Even if these disclosures appear intact on some screens, the disclosures would still violate the settlement's requirement of “unavoidable” notice: The disclosures would appear below and behind the ActiveX, in an inactive window whose significance is deemphasized by the superseding ActiveX prompt. Because the ActiveX window is “modal,” users cannot switch to the rear window even if they specifically attempt to do so (e.g. by clicking on the desired window – the usual Windows procedure to bring a window to the foreground). Under these circumstances, reasonable users focus on the active, center-screen ActiveX prompt without noticing the small text in the inactive window behind.

Zango's ActiveX sequence shares many characteristics with a Direct Revenue ActiveX installation sequence the FTC specifically criticized in separate litigation. See the FTC's complaint in In the Matter of DirectRevenue LLC:

“Often, the web pages offering the lureware did not disclose that, by installing the lureware, respondents' adware would also be installed on consumers' computers. In many instances, the only way for consumers to learn about the existence and effects of respondents' adware was to click through one or more hyperlinks to reach multi-page user agreements containing such information. These inconspicuous hyperlinks were located … in a modal box provided by the computer's operating system. Consumers were not required to click on any such hyperlink, or otherwise view the user agreement, in order to install the programs. Examples of this tactic include, but are not limited to, the following: … Bundling adware, without adequate notice, with their own lureware distributed to consumers via an Active-X box entitled “Security Warning.”

Just as DirectRevenue's “lureware” disclosed its effects only through a multi-page user agreement linked from an ActiveX “Security Warning” box, so too does this Zango ActiveX installation disclose its effects only through a link from the ActiveX box. The FTC's specific criticism of DirectRevenue's ActiveX approach indicates that the FTC is not likely to approve of Zango's similar use of ActiveX.

Scope and Duration of These ActiveX Installations

These Zango ActiveX installations arise from Zango banner ads that are widespread. I have personally observed these banner ads syndicated to dozens of sites across the web. Zango achieves particularly broad distribution of these ads by commissioning their display via several top ad networks, including ValueClick's FastClick as well as Right Media's YieldManager. (Sunbelt Software also recently reported Zango advertising running through Right Media.)

These Zango ActiveX installations continue Hotbar installations that I critiqued on my web site more than two years ago. See Hotbar Installs via Banner Ads at Kids Sites (May 2005). There, as here, installation began with a misleading ad (offering lureware with no mention of pop-up ads). There, as here, installation continued to an ActiveX without on-screen “clear and prominent” disclosure of material terms. There, as here, the subsequent “Welcome” screen lacked a cancel button. I publicly critiqued each of these practices in 2005, but Zango nonetheless continues each of these practices in the ActiveX installation sequence set out above.

to topWidespread Zango Banner-Based Installations without Unavoidable, Prominent Disclosure of Material Terms (XP SP2)

On computers running Windows XP Service Pack 2, the installation sequence described in the preceding section appears somewhat differently. But the core shortfall is the same: Here too, Zango installs without unavoidable and prominent disclosure of material terms. Installation proceeds in five steps:

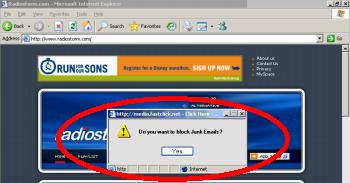

1) Various web sites serve ads like that shown in the top screenshot at right. In the example shown in at right, a freestanding popup asks “Do you want to block Junk Emails ?” (s.i.c.). In some instances, these installations begin with a Zango banner ad embedded within a third-party publisher's web site (as shown in the first screenshot of the preceding section).

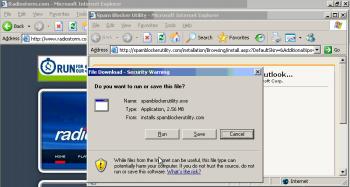

2) If a user clicks Zango's ad in step 1, the user is taken to the landing page shown in the second screenshot at right. The screenshot shows that landing page just as IE displayed it (without any adjustment of its size or shape). Bullet points tout the various features Zango promises (“Protects your Inbox from annoying Junk mail”, s.i.c., etc.), but Zango makes no mention of any adverse effects or any bundled advertising whatsoever. An animated red arrow encourages users to press a button labeled Free Download.

3) If a user presses the Free Download button, the user receives the standard Internet Explorer download confirmation screens shown in the third and fourth screenshots at right. These are standard IE SP2 screens shown during any EXE download.

4) Zango then shows a screen captioned “Welcome to the Spam Blocker Utility Installation” (the fifth screenshot at right). This screen presents a lengthy End User License Agreement (4,070 words, 45 on-screen pages) within a scroll box. The first page of the EULA mentions the single word “advertising” without any specific disclosure of the type of advertisements (e.g. pop-up ads and in-toolbar ads). The first page mentions that “our [Zango's] software collects information” but says absolutely nothing about the nature of information collected, or about where that information is sent or how it is used.

5) Finally, Zango asks the user to choose between the “free ad-supported version” and the “Paid version” (the bottom screenshot at right). But as explained in the prior section, this choice is illusory: Nowhere does Zango describe the kind of ads at issue, nor does Zango offer any abort or cancel option for users who want neither ads nor a charge.

If a user chooses the “ad-supported” option, Zango installs in full -- including its browser toolbar and its pop-up ads. Users have no further opportunity to cancel installation.

Analysis of Zango's SP2 Installation Sequence vis-à-vis Zango's FTC Settlement Obligations

This Zango ActiveX installation falls short of Zango's obligations under its settlement with the FTC. As set out in the preceding section, Zango is required to provide “clear[] and prominent[] disclosures” of its material terms. This installation does not do so. In no on-screen text does Zango mention the kinds of ads to be shown, nor does Zango's on-screen text disclose any privacy consequences whatsoever.

To the extent that Zango provides any disclosure of ad formats or privacy effects, such disclosure appear only in an End User License Agreement. Disclosure in Zango's lengthy license is exactly contrary to the settlement's requirements that such disclosures appear “prior to the display of, and separate from, any [EULA].”

Effects of Zango's “Fake User Interface” Advertisements

The Zango popup shown in the top screenshot in this section is a “fake user interface” ad – designed to look like a standard Windows message box, and therefore to suggest that the message comes from software the user has previously installed. In particular, the Zango popup substantially matches the fonts, background color, “attention” icon, and button labeling and placement of standard Windows MsgBox() dialog boxes. As a result, many users are likely to mistakenly conclude that this window comes from software already installed on their computers – without realizing, at least initially, that the window is actually an advertisement from a company with which the user has no preexisting relationship. Expert users can distinguish Zango's fake user interface ads from genuine Windows messages; careful, detailed examination does reveal important differences. But hurried and novice users nonetheless face high risk of misunderstanding the source and significance of Zango's fake user interface ads.

The FTC has previously held that advertisements must be labeled as such when failure to label an advertisement would deceive consumers. (See e.g. Statement in Regard to Advertisements that Appear in Feature Article Format, 3 Trade Reg. Rep. (CCH) Para . 7559 (1967), holding that an affirmative disclosure is required if consumers would be led to believe that an advertising feature was part of a newspaper's editorial content.) Reasonable users are likely to grant greater deference to a message that appears to come from software already on their computers (e.g. from Windows itself) than on a mere advertisement delivered from a third party. Zango's fake user interface ads therefore pose a substantial risk of deceiving users, and ought at least be labeled as ads -- if not eliminated entirely, in favor of some alternative design substantially less likely to deceive.

to topOngoing Zango Installations with No Disclosure Whatsoever

Some third-party programs continue to install Zango software onto users' computers with no disclosure whatsoever. Consider the installation sequence shown in the accompanying set of screenshots. A user begins at the MSN-Emotions site (first screenshot) (unaffiliated with Microsoft or the "real" MSN). The user scrolls down to the section captioned “Download thousands of MSN Emotion smileys here!” (second screenshot). Clicking on the link labeled “Download Here”, the user receives an Internet Explorer confirmation box (third screenshot) which leads to a ZIP file (fourth screenshot). Running the “Adder.exe” program within this ZIP immediately places Zango advertising software onto a users' computer. In no on-screen text is Zango mentioned by name or even by its general effects.

This nonconsensual undisclosed installation of Zango software stands in sharp contrast to Zango's obligations under its settlement with the FTC. Settlement III specifically prohibits “install[ing] or download[ing] .. any software program or application without express consent.” That the Zango software was placed onto user' computers by MSN-Emotions is irrelevant under the plain language of the settlement: Settlement III covers actions Zango takes “directly” as well as those taken “through any person, corporation …, division, affiliate, or other device” – any of which would cover MSN-Emotions. Zango may claim to lack control over MSN-Emotions, but the settlement's broad "through any person ..." requirements nonetheless hold Zango responsible for those who distribute its software.

In November 2006, I reported this nonconsensual installation of Zango software. See Example D: Msnemotions Installing Zango with No Disclosure At All within Bad Practices Continue at Zango, Notwithstanding Proposed FTC Settlement and Zango's Claims . Nonetheless, more than seven months later, these installations continue. See video proof, showing this installation still operational as of July 4, 2007.

to topUnlabeled Ads - Toolbars, Desktop Icons, and Pop-ups

In various contexts, Zango still fails to label ads at all, not to mention in the manner required by the FTC settlement. This section provides three specific examples of Zango ads without the FTC-specified labeling.

Zango Toolbar Still Displays Unlabeled Ads

Zango Toolbar software continues to show unlabeled ads within an Internet Explorer toolbar. See the screenshot at right (prepared July 10, 2007).

These unlabeled in-toolbar ads specifically violate Zango's obligations under its settlement with the FTC. Settlement VI requires that Zango “clearly and prominently” identify the program that delivered each advertisement, and that Zango further provide a “clear[] and prominent[]” hyperlink by which users can uninstall and/or submit complaints. The obligations of Settlement VI apply to “any advertisement served or caused by [Zango's] software program or application installed on consumers' computers.”

Zango's in-toolbar ads fall within the scope of “any advertisement,” and the display of these ads in browser toolbars falls within “software program[s] or application[s] installed on consumers' computers.” The plain language of the settlement therefore requires that the ads be labeled with Zango's name and with the specified links. Yet Zango systematically omits such labeling – even seven months after I specifically flagged this exact issue.

To the extent that Zango provides any support information, users must click on a button labeled “More,” then on a button menu option labeled “Zango,” then on a button labeled “Support” (or, alternatively, “More” – “Zango” – “About Zango”). This multi-step procedure cannot satisfy the “unavoidable” requirement within the definition of “clear[] and prominent[]” disclosure. Furthermore, Settlement VI requires that “such hyperlink [to uninstall instructions] shall be clearly named to indicate [this] function[]” – but Zango's use of the labels “Support” and “About” are not “clearly named” to offer assistance with uninstall.

Zango Hotbar Places Unlabeled Icons onto Users' Desktops

Certain Zango software, including Zango's Hotbar software, also places unlabeled and unattributed advertising icons onto users' desktops. See the screenshot at right (prepared on July 25, 2007). These icons are advertisements, in that they promote paid third-party software. The icons therefore fall within Zango's Settlement VI labeling and hyperlink obligations. Yet the icons lack the labeling specified by Settlement VI. Notice that the icons lack any labeling of the fact that they came from Zango. Neither do the icons include any information about uninstall or complaint procedures.

Zango Displays Ads without On-Screen Labeling and without On-Screen “X” to Close

In testing of February 6, 2007, I received the Zango-delivered ad shown in the top screenshot at right. The ad appeared without any on-screen labeling of the ad's origin, and without any on-screen indication of the fact that the ad came from Zango. The ad appeared with its upper-right corner off-screen – making it impossible to close the ad via the standard Windows procedure of clicking the upper-right “X” button. See video proof of what occurred.

Dragging the pop-up onto the screen, I confirmed that this ad was indeed delivered by Zango. See the second screenshot at right.

JavaScript code within the ad reveals that its placement was not accidental. The ad's code specifically checked for any window size less than 840 pixels in width or less than 600 pixels in height. Finding such a size, the ad automatically resized itself to achieve the specified size. But by making the ad both wider and taller, the ad pushed its “X” button off the right edge of the screen, and pushed its label off the bottom of the screen. The JavaScript code at issue:

if (document.body.clientWidth < 840 || document.body.clientHeight < 600)

{

window.resizeTo(840, 600);

}

This off-screen labeling falls short of Zango's obligations under its settlement with the FTC. The ad at issue lacked a “clear[] and prominent[]” identification, and the ad also lacked a “clear[] and prominent[]” hyperlink to uninstall instructions and a complaint procedure.

to topZango Ads for Bogus Sites that Attempt to Defraud Users

Widespread Zango pop-up ads promote programs that attempt to defraud users – including by making false claims, and by charging for software that is actually free, among other practices. These pop-ups are served by all current Zango software, including Zango's namesake program, Hotbar, Seekmo, and SpamBlockerUtility.

Zango Displays Click-to-download, which Charges for Skype

Consider the screenshot shown in the screenshot at right (prepared on July 5, 2007). I searched for “skype” at Google. Zango covers Google's search results with a large window showing Click-to-download.com. The window's large size and foreground placement, its prominent stylized “Skype” text, its use of the Skype logo, and its oversized “Download now” button all serve to entice users – falsely suggesting that this may even be the official way to receive Skype software. But if a user clicks the Download Now button, he is taken to a page where Click-to-download demands a $19.95 payment. This fee stands in stark contrast to the terms available at Skype.com – where the software would have been offered without any fee whatsoever.

Click-to-download appears only because Zango elects to show that site. Google shows no such listings, either in ordinary results or as ads, within current search listings for “Skype.” So Zango is the proximate cause of users' exposure to Click-to-download. A user without Zango will not see the Click-to-download site and thus will not risk paying Click-to-download an unnecessary and unwarranted $19.95.

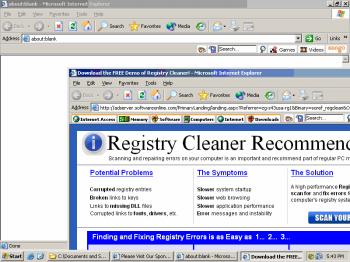

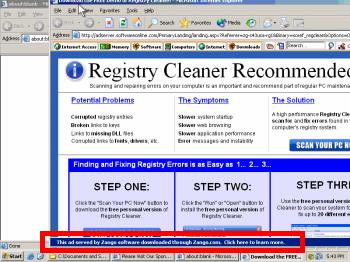

Zango Displays Registry Defender, which Falsely Claims to Have Scanned for Registry Problems

Zango also shows ads that make false statements as to the state of the user's computer security. Consider the screenshot shown at right (also from July 5, 2007). I searched for “remove spyware” at Google, and Zango opened the Registry Defender pop-up shown in the foreground. The pop-up claims to be “Scanning [the] registry” – but in fact the “Scanning” text and accompanying green status bar are merely pictures, shown even though no bona fide scanning is occurring or has occurred. Furthermore, although the pop-up reports that my computer runs Internet Explorer 4 (an old version with numerous serious security shortfalls), my computer actually was running version 6.

The Registry Defender pop-up thus misstates both a user's need for security assistance (by falsely claiming I run old software requiring updates) as well as the extent of its examinations (by falsely claiming to have run a registry scan, when it did not). Here too, a user only receives this misleading pop-up as a result of having Zango installed. Were it not for Zango, this pop-up would not have appeared.

As in the case of Click-to-download, Registry Defender's motive is pecuniary and direct: Registry Defender seeks to charge users $29.95 for its software. Users who run Zango therefore face a heightened risk of paying this unnecessary charge, based on false diagnostics of supposed problems they do not actually experience.

Zango Displays Other Dubious Ads

Beyond the prior two examples, Zango also displays numerous other dubious ads. For example, many widespread Zango ads promise users something for free -- only to require a lengthy signup process of numerous trial offers users are unlikely to satisfy. Other Zango ads promote sites that send users exceptionally high volumes of emails -- as many as several hundred per week, in tests conducted by SiteAdvisor.

to topZango's Practices in Context

When Zango and the FTC announced their settlement, Zango claimed that it had "met or exceeded the key notice and consent standards since January 1, 2006." I emphatically disagree. With widespread ongoing installations that fail to provide the notice required under the settlement, Zango cannot claim to provide the necessary notice before installing. And with widespread toolbar, desktop icon, and even popup ads still lacking the labeling required under the settlement, Zango cannot claim to be consistently providing the on-ad notice the settlement demands.

In a letter to me and to Eric Howes, responding to our concerns about enforcement of the FTC's then-proposed settlement with Zango, the FTC said it "recognizes that it must be vigilant regarding Zango's conduct once the proposed order becomes final." I have previously remarked on FTC enforcement actions I consider too timid or narrow (echoing the position of FTC Commissioner Leibowitz). Whatever my prior concerns, these widespread violations by Zango offer the FTC a clear opportunity to demonstrate the importance of full compliance with settlement terms. I look forward to a tough and effective response from the FTC.

to topCritiquing Zango's Response

In a blog post, Zango attacks the preceding analysis as an "unfounded, inaccurate, and misleading" "manifesto." Zango further accuses me of "manipulat[ing]" facts about Zango's practices.

Putting aside the personal attack, let me quote Zango's substantive claims and offer a brief reply.

Zango: "Edelman focuses on heritage Hotbar, Inc. products, particularly SpamBlockerUtility (SBU) – products that simply are not addressed in the FTC-Zango consent agreement. No Zango product covered by the consent agreement is installed via ActiveX. Edelman's failure to realize the inapplicability of the consent agreement (or, if he does, to disclose that fact) to SBU speaks volumes."

First, FTC Settlement III specifically applies to "any software program" Zango "install[s] or download[s]." This provision makes no exception for any "heritage" software.

Second, the SpamBlockerUtility software definitely does install Zango software, i.e. the standard Zango software that tracks usage and shows pop-up ads, as well as the Zango Toolbar. See video proof (prepared July 13, 2007) showing a SpamBlockerUtility installation, immediately followed by a Zango pop-up. Zango may call these "heritage Hotbar products," but their pop-up ads are identical to ordinary Zango pop-ups. Furthermore, these pop-ups use the same ad-targeting mechanisms as standard Zango pop-ups (including the same "kyf" keyword file and the same "showme.aspx" communications with Zango's servers)

In an Information Week piece, Richard Purcell (former Chief Privacy Officer of Microsoft, but now a consultant to Zango) claimed my analysis depicts "Hotbar installations," which he says are "specifically called out as not being part of [Zango's] settlement [with the FTC]." But the settlement's broad language ("any software program") clearly covers any program Zango distributes, including the Hotbar software Zango purchased in 2006. The only settlement provision that mentions Hotbar by name is Settlement I, which covers only treatment of legacy software already installed on users' computers, but says nothing about installation requirements for new installations. In any event, these installations deliver Zango's pop-up software. So even if there were "a Hotbar exception," that exception wouldn't cover Zango's pop-up ads.

Finally, Zango seems to suggest that these SpamBlockerUtility (and similar) ads are obscure or hard to find. I emphatically disagree. To the contrary, these ads are widely syndicated across the web through top ad networks, including ValueClick's FastClick as well as Right Media's YieldManager. I described these installation sequences as "widespread," and I stand by that characterization.

Zango: "[E]ven when seemingly looking at a Zango product, Edelman fails to disclose that his screenshots and videos capture an outdated, discontinued version of that product no longer supported or made available by Zango. ... Saving a disabled file to a computer does not constitute 'Ongoing Zango Installations.'"

My article says nothing the contrary. In the single article section that covered an older Zango product, I never claimed that the software showed any ads. Rather, I flagged the remarkable fact that this installation still occurs -- seven months after I first wrote about it. Zango had ample opportunity to see to it that the installation file was removed from the web server that, to this day, still provides it. Had Zango gotten the file removed, Zango could have prevented further users from receiving Zango software through this bundle, without any notice whatsoever. Zango ought to have done so. Instead, as a direct result of Zango's failure to remove the file, users can still receive Zango software with no notice or consent

Separately, Zango takes issue with my claim that these are "installations" of Zango software. Let's review the core facts, which are not in dispute. This Zango distributor 1) places Zango's software onto a user's computer, and 2) sets Zango's EXE to run each time a user turns on his computer (via the Windows HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run registry key). What does it mean to "install" Zango? My answer: Placing Zango software onto users' computers, and causing that software to run on boot. Zango correctly notes that the resulting software currently does not show ads. But the fact that the product shows no ads does not mean the product is not "install[ed]" when its files are placed on disk and when its EXE is set to run on startup.

Zango: "Edelman manipulates his research tools – without disclosure to the reader. ... Edelman's screenshot purporting to show differently [i.e. unlabeled ads] is taken from an archaic computer with low or outdated screen resolution."

I prepared all screenshots on a standard VM with 800x600 resolution. I have used that same resolution for all VM testing, dating back to my initial 2003 purchase of VMware. Perhaps Zango thinks its products look better at other resolutions, but it's not "manipulat[ion]" for me to continue the same testing method I've always used.

Zango goes on to claim its toolbars would have shown a label had I only run tests at a higher screen resolution. But Settlement VI obliges Zango to place labels on all ads, not just on ads shown on large or high-resolution screens.

Zango: "[W]hen manufacturing 'proof' of his accusation that 'Zango Displays Ads Without On-Screen Labeling and Without On-Screen 'X' to Close,' Edelman intentionally utilizes outdated PC technology to make his argument. As Edelman himself points out (eventually), the ads are labeled, and there are numerous ways to resize and close the ad."

My article claims that the specific ad at issue lacks "clear[] and prominent[]" on-screen labeling as required by the FTC settlement. I credit that the ad includes a label -- but the label is off-screen. The FTC's definition of "clear[] and prominent[]" requires, among other characteristics, that labels be "unavoidable" and that they "shall appear on the screen." An off-screen label cannot meet these requirements.

That there are multiple ways to close an ad is irrelevant. Placing an ad's "X" off-screen makes it harder to close the ad -- particularly for hurried or novice users. Zango ought to take extra steps to assure that all its ads can be closed easily, through a single click, and using the standard method of a simple on-screen "X."

I don't know what "outdated PC technology" Zango thinks I used. The fact is, that test used the same base VM image as all my other tests -- complete with IE6 (notwithstanding a Zango advertiser's false claim that I was using only IE4).

Posted: July 31, 2007. Sign up for notification of major updates and related work.