My January 2014 “Darker Side of Blinkx” explored Blinkx’s adware business and other controversial practices. The posting prompted significant interest, but unexpectedly much of the subsequent discussion focused on why I did the work rather than Blinkx’s actual practices. With this piece, I further examine of Blinkx’s adware, deceptive installations, and other tactics that harm both users and advertisers.

In remarks last week, Blinkx attributed Zango’s downfall to “lax oversight of rogue partners.” In today’s article, I show similar problems among Blinkx’s installations. I begin with deceptive installation of Blinkx adware when users request a (nonexistent) Flappy Bird game — an abusive bait-and-switch installation that burdens a user with half a dozen different adware programs yet never provides the promised game. I then show similarly deceptive installation of Blinkx adware when users request a (nonexistent) Snapchat app for Windows. I compare these practices to FTC requirements and evaluate Blinkx’s defenses. I then to demonstrate Blinkx that adware undermines HTTPS security by collecting and retransmitting users’ seemingly-secure browsing activity, as well as showing deceptive advertisements that targeted web sites would never allow along with numerous ad-fraud popups that charge merchants for traffic they would otherwise receive for free. I then find Blinkx adware loading Google ads in pop-ups, which specifically violates Google ad placement rules. I conclude with recommendations and next steps.

Note that this article examines only Blinkx’s ex-Zango adware business — not its ex-AdOn traffic brokering or its various other activities.

Deceptive Installation: Fake Flappy Bird App Installs Blinkx Adware

Softdlspro claims to offer a “Flappy Birds Game Download.” The bundle provides myriad adware including Blinkx adware, but no Flappy Birds.

Softdlspro claims to offer a “Flappy Birds Game Download.” The bundle provides myriad adware including Blinkx adware, but no Flappy Birds.

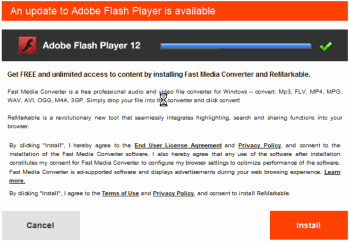

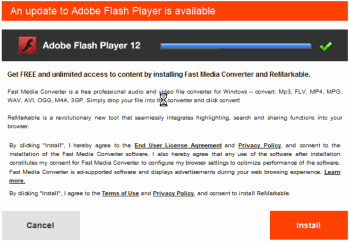

Deceptive Fast Media Converter installation solicitation pretends to be a Flash Player update. It installs Blinkx adware (and more).

Deceptive Fast Media Converter installation solicitation pretends to be a Flash Player update. It installs Blinkx adware (and more).

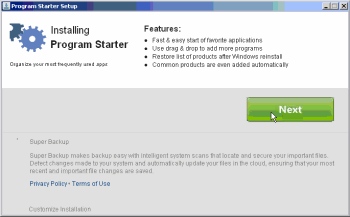

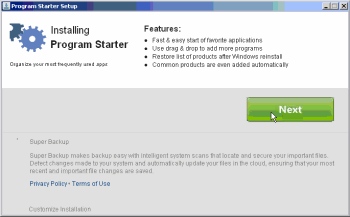

Deceptive Super Backup installation puts the Next button above disclosures, and makes no mention of any popups or any advertising at all.

Deceptive Super Backup installation puts the Next button above disclosures, and makes no mention of any popups or any advertising at all.

A decade after the dawn of adware, one might ask why users agree to install programs that slow their computers, reduce their privacy, and bombard them with pop-up ads. A close look at Blinkx installs is instructive: Often, users aren’t fairly told what they’re getting. Though FTC rules call for clear disclosure of key effects, in prominent text outside a license agreement, Blinkx and its partners often omit these statements. That omission isn’t just an occasional error — it’s a common characteristic of many Blinkx installations. Yet the omission is no great surprise: If Blinkx and its partners fairly told users what they’d be getting, most users would decline. The following sections show installations with this problem (among others).

On February 10, 2014, Flappy Bird creator Dong Nguyen withdrew his popular game from Apple and Google’s app stores. In response, users went to search engines to try to get the game. Users searching on Google often saw ads that promoted a Softdlspro page that purported to offer “Flappy Bird Game Downloads” but actually had no such thing. Through this process, unfortunate users received Blinkx adware.

In the top screenshot at right and in a first video, I demonstrate that a search for “flappy birds” took users to a Softdlspro download page. In a second video, I then show that this Softdlspro bundle bombards users with an onslaught of adware. In my testing, a user who attempts to install this game is asked to install Fast Media Converter adware (video at 2:42), Program Starter (3:51), Yahoo Toolbar (3:55), Gamevance/Trafficvance ArcadeParlor adware, “Clean Water Action Reminder” from We-Care (a browser plug-in that monitors users’ browsing and claims affiliate commission on users’ purchases) (4:02), SLOW-PCfighter (which purports to offer computer repair) (4:03), and Super Backup (4:08).

This Softdlspro “Flappy Bird” bundle appears to install two different programs with Blinkx adware. First, Softdlspro touts Fast Media Converter, which installs Blinkx ex-Zango adware. I credit that the FMC site and EULA give no immediate indication that FMC installs Blinkx adware. But taken as whole, the installation leaves litle doubt. Relevant factors: FMC retrieves configuration files and advertisements from URLs that match standard ex-Zango patterns. FMC’s pop-up ads match the longstanding Zango format including the same user-interface and delivery methods. (Examples: FMC popups defraud Amazon by claiming commission on Amazon’s organic traffic. FMC popups claim a “New Version Available” and use the Chrome name and logo. FMC popups claim “your Video Player has a faster version available” and use the Internet Explorer name and logo. FMC popups claim “Outdated Browser Detected” and repeatedly use the Internet Explorer name and logo.) In addition, the FMC installer downloads component EXEs from Premium-apps.net, which is Ignition Installer run by Verti Group, a Blinkx subsidiary.

Second, Softdlspro’s “Flappy Bird” touts Super Backup which is also monetized by Blinkx. Super Backup more readily discloses the link to Blinkx: Its Privacy Policy (visible in the video at 4:17) describes the program’s advertising component as “LeadImpact Software,” and its Terms of Use say the same thing. Furthermore, LeadImpact’s privacy policy says LeadImpact comes from Pinball Corp, and LeadImpact’s DNS servers are also within pinballcorp.com. Notably, Blinkx’s 2010 annual report lists Pinball as a wholly-owned subsidiary. LinkedIn statements are in accord: Tony Gozzo describes his employer as “the Leadimpact division” of Blinkx, and Ramon Navarro says he works for “Leadimpact – a division of Blinkx.”

The Softdlspro “Flappy Bird” bundle is deceptive for multiple reasons. For one, it never provides the game the user requested and the offer purports to provide. Any associated “consent” to receive adware is therefore ill-gotten; as Softdlspro didn’t hold up its end of the bargain.

Furthermore, the Softdlspro offers are less than forthright. Consider the Fast Media Converter solicitation that appears in the video at 2:42 and in the second screenshot at right. (In general this is a freestanding offer — it appears on its own web page, separate from the Softdlspro install window, so users can and do receive this offer from other sources. That said, the Softdlspro installer systematically opens this web page, so users in the fake Flappy Birds install sequence are bound to see this pitch too.) The FMC offer reads “An update to Adobe Flash Player is available,” prominently references “Adobe Flash Player 12”, and uses the distinctive Adobe logo. But the software at issue is not provided by, or in any way affiliated with, Adobe. Indeed, Fast Media Converter has no genuine connection to Adobe Flash Player, and FMC uses the Adobe name, logo, and trademark only to appear familiar and legitimate. Users may be induced to install software because they are told it will “update” software they genuinely want on their computers. But when Blinkx and its distributors falsely claim to provide updates to unrelated software, any user’s “agreement” is ill-gotten and invalid.

FMC’s disclosures are also cause for concern. FMC mentions advertisements in a single clause midway through its installation disclosure (third paragraph, next-to-last sentence) — a place where users are unlikely to notice. Furthermore, the disclosure is vague: FMC “is ad-supported software and displays advertisements during your web browsing experience.” Missing from this disclosure are the two key facts FMC needs to convey to users before asking them to accept the adware: First, that ads appear in pop-ups, a format users are known to dislike. Second, that the adware tracks users’ browsing in detail and at all times. Such disclosures are required to alert users to the material consequences of the installation, and such disclosures are specifically required under longstanding FTC rules. See analysis below.

In some respects, the Super Backup installation is even more deceptive. For the on-screen display, see the video at 4:08 and the third screenshot at right. Prominent on-screen disclosures are placed above the oversized green “Next” button. But these disclosures only mention innocuous features about a program launcher. (These features are associated with Program Starter, a bundler that solicits a series of further installations.)

- Blinkx’s Super Backup is mentioned in a format that invites users to overlook what they are purportedly accepting. The disclosure is in grey type on a grey background (text color RGB 128 128 128 against 224 224 224, whereas black on white would be the higher-contrast 0 0 0 on 255 255 255).

- The disclosure is at the far bottom of the window, outside the natural flow of a user’s review from top to bottom. Indeed, a user reading the window from top to bottom would have already have reached (and perhaps clicked) the Next button before reaching the disclosure.

- The Next button does not solicit a clear manifestation of assent. To obtain meaningful permission to install, Biinkx and its partners would need a label like “I accept” or “I agree.”

- Worst of all, the disclosure says nothing at all about advertising. It only mentions backup functions: “makes backup easy with intelligent system scans…” A user reading this description would conclude that Super Backup provides backup with no advertising at all. But in fact Super Backup uses the ex-Zango adware engine to present users with popup ads.

These Super Backup practices fall short of legal requirements, including the duty to disclose material effects outside the license agreement. See analysis below.

Deceptive Installation: Fake Snapchat App Installs Blinkx Adware

Soft1d claims to offer a Snapchat download. The bundle actually provides myriad adware including Blinkx adware, but no Snapchat app.

Soft1d claims to offer a Snapchat download. The bundle actually provides myriad adware including Blinkx adware, but no Snapchat app.

In February 2014, I used Google to search for a Snapchat app from a Windows PC. Sophisticated users may know that there is no such app — Snapchat is for phones only. But in my testing (preserved in video), my request yielded a Soft1d page ad touting an app purportedly entitled “Snapchat.” I clicked Download Now (0:10), ran the resulting installer, and ultimately received no Snapchat app — but I did receive numerous adware including adware funded by Blinkx ads. Specifically, the bundle included Program Starter (1:40), a deceptive Fast Media Converter “Update to Adobe Flash Player” solicitation (1:49), Yahoo Toolbar (3:40), Savings Bull (3:42), Gamevance/Trafficvance Arcade Parlor adware (3:43), “Clean Water Action Reminder” from We-Care (3:48), and SLOW-PCfighter (3:50).

These installations are deceptive for the same reasons detailed in the preceding section.

Chris Boyd of ThreatTrack Labs critiqued this same installation in a posting dated November 19, 2013. Yet the same practices continued three months later in February 2014. To my knowledge, these practices are ongoing.

Blinkx might like to write off these practices as rogue affiliates or subaffiliates. Such a response would be ironic after Blinkx attributed Zango’s downfall to “lax oversight of rogue partners.” Most importantly, these installations are the norm and not the exception: When I find a distributor asking users to install Blinkx adware, the distribution has defects like these as often as not.

Blinkx says users who receive its adware are “getting utility for free in exchange for being served ads.” Blinkx further claims “the user experience is explicit and clear” and “the installation process is unambiguous.” Blinkx even touts a “25 point evaluation check list” for every app it considers as a distributor for its adware. But the installations speak for themselve; whatever Blinkx is doing, it’s not enough. The fact is, Blinkx’s distributors are pushing its adware through deception — claiming to be “Update to Adobe Flash,” promising apps like Flappy Bird and Snapchat that they don’t even provide, and failing to disclose key effects in the way the FTC requires.

Relevant FTC Requirements

The FTC Act bans “unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce” (15 USC 45). Cases interpret the prohibition on “deceptive” practices to disallow conduct that is “likely to mislead” (Gill , 71 F.Supp.2d at 1037, citing Southwest Sunsites, Inc. v. FTC, 785 F.2d 1431, 1436 (9th Cir. 1986)). In litigation evaluating a FTC complaint, a court examines a defendant’s representation to determine whether the “net impression” is likely to mislead reasonable consumers. See FTC v. Cyberspace.com, LLC , 453 F.3d 1196, 1200 (9th Cir. 2006). Notably, it is not a sufficient defense for a defendant merely to disclose the truth somewhere. FTC. v Cyberspace.com is on point: “A solicitation may be likely to mislead by virtue of the net impression it creates even though the solicitation also contains truthful disclosures” (emphasis added). See also Removatron Int’l Corp., 884 F.2d at 1497 (examining the “common-sense net impression” of an allegedly deceptive advertisement).

Caselaw on “unfair” advertising takes an equally dim view of Blinkx’s tactics. The FTC’s Policy Statement on Unfairness disallows behavior that causes or is likely to cause substantial consumer injury that a consumer could not reasonably avoid, and is not outweighed by the benefit to consumers. Blinkx might argue that users can avoid its adware by declining installation solicitations. But the vague, unclear, and otherwise-deceptive installation disclosures make it difficult for a reasonable user to understand what they are asked to accept and to recognize the importance of declining. Meanwhile, in the examples I presented, Blinkx adware fails to offer a single benefit to consumers. Indeed, Blinkx and its partners never provide the promised benefits (e.g. the Flappy Birds game or Snapchat app), so users receive only the detriment of extra advertising and tracking, without the promised benefit. The failure to provide the promised benefit is an exceptionally clear case of lack of countervailing benefit.

Squarely on point, the FTC has long held that adware may only be installed after providing a clear and conspicuous notice of key effects. For example, in 2008 testimony, Eileen Harrington (FTC Deputy Director of the Bureau of Consumer Protection) described the FTC’s view of appropriate practices for adware vendors. Specifically, Harrington stated that “buried disclosures … are not sufficient.” She continued: “burying material information in an End User License Agreement will not shield [an adware] purveyor from Section 5 liability.”

Despite Director Harrington’s statement of applicable requirements, these examples indicate that Blinkx and its distributors are disclosing key practices at most in license agreements, not in prominent on-screen text. In this crucial respect, Blinkx’s practices are exactly contrary to Harrington’s statement of the FTC’s longstanding generally-applicable requirements for adware.

Critiquing Blinkx’s Response to Deceptive Installations

In its response to my January article, Blinkx argues that “Ad supported … options are valid, recognized and accepted alternatives for packaging and distributing premium content.” Blinkx goes on to compare its adware to the Google Chrome web browser, noting that both show ads and that there is nothing inherently wrong with showing ads. (“Chrome is itself ad-supported software distributed by Google.”) Blinkx even compares itself to “mainstream publishers, such as MSNBC.com and People.com,” which also show advertising and sometimes popups. But this misses the concern completely. Google Chrome shows ads in the program window, when it is in use, and at no other times. MSNBC shows ads when a user visits its site, but at no other time. Blinkx adware is quite different: It runs at all times; it tracks users’ browsing and sends users’ activities to Blinkx servers; and it shows frequent popup ads. This could hardly be more different than mainstream web advertising. Moreover, my piece did not criticize ad-supported software in general. Rather, I criticized deficient disclosures that give users no clear statement of what they are (purportedly) accepting. The absence of informative disclosures leads users to “accept” software that, unbeknownst to them, is actually adware they would never have agreed to receive, had they been aware of its true effects.

Blinkx then argues that whatever installation problems occurred, they are not its responsibility. For example, I presented an unauthorized Google Chrome package that (contrary to Google’s Chrome Terms of Service) included Youdownloaders code which installed Desktop Weather Alerts which is Blinkx adware. To this, Blinkx argued that “Youdownloaders is a third party distributor and is neither blinkx nor a blinkx affiliate.” But I never claimed Youdownloaders had a direct relationship with Blinkx. The best description of Youdownloaders is a Blinkx subaffiliate: By all indications, Blinkx pays Desktop Weather Alerts to place Blinkx adware on users’ computers, and then Desktop Weather Alerts in turn pays Youdownloaders. But this chain of relationships in no way relieves Blinkx of responsibility for the underlying installation practices. Indeed, in 2006 litigation against Zango (the very company that created the adware here at issue), the FTC noted that Zango acted “through affiliates and sub-affiliates.” Reinforcing the importance of this business structure, the FTC repeated that phrase six separate times in five paragraphs. Similarly, the FTC’s 2007 order specifically indicated that its obligations apply both to Zango and to any intermediaries Zango chooses to use: In five separate paragraphs, the order repeats that its obligations apply to Zango directly and also to acts “through any person, corporation, subsidiary, division, affiliate, or other device.” Moreover, the FTC further noted that, at best, Zango had failed to adequately supervise its affiliates and their subaffiliates when acting on Zango’s behalf: “Respondents knew or should have known that there was widespread failure by their affiliates and sub-affiliates to provide adequate notice of their adware and obtain consumer consent to its installation.” In such circumstances, the FTC found that Zango was liable for the actions of its affiliates and subaffiliates. The same principle applies to Blinkx.

Relatedly, Blinkx argues that even the conduct of Weather Alerts is not Blinkx’s responsibility because “blinkx does not own Weather Notifications.” But Blinkx admits two sentences later that it “does maintain a commercial relationship with Weather Notifications, where the Company provides the monetization engine for this application and others like it.” Indeed, link Zango, Blinkx has numerous distributors who place its adware onto users’ computers. Zango has historically arranged its partnerships so that its affiliates all used the same name — all installing, at one time, “Zango” adware. Blinkx has now structured its affairs somewhat differently — causing affiliate Weather Notifications to distribute adware with one set of names (including Desktop Weather Alerts) while other affiliates distribute Blinkx adware under other names (such as Fast Media Converter and various others). But the chosen names are irrelevant. Notice Blinkx’s crucial roles: Like Zango, Blinkx provides the adware engine that monitors users’ behavior, targets ads, and displays ads. Furthermore, like Zango, Blinkx sells the ad inventory to advertisers, including receiving advertisers’ requests about which popups to show when users visit which pages and search for which keywords. Consistent with prior litigation and longstanding principles of agency, these efforts make Blinkx responsible for the associated adware. Introducing more product names serves primarily to reduce accountability by making it harder for users to figure out whose adware they are actually running, what company made the adware engine, or who to complain to. But multiple product names do not reduce Blinkx’s responsibility for the underlying practices.

Blinkx and its defenders took issue with a portion of my January article that said certain adware “is part of Blinkx” when the adware is distributed by a third party. But under the FTC’s articulated standards and caselaw, Blinkx is responsible when adware shows ads sold by Blinkx, when Blinkx makes the adware engine that presents the ad, and indeed when the entire advertising delivery system uses Blinkx (ex-Zango) code. In each of the examples I presented previously and above, Blinkx plays these roles. That Blinkx chooses to label its software with the names of third parties such as Weather Alerts and others, rather than under its own name, is of little import to users. Notably, these distinctions are also of no consequence to the FTC, as discussed above.

Blinkx further suggests that Google may even have authorized Youdownloaders to redistribute Chrome and to bundle Chrome with multiple adware programs: “It is quite likely that Youdownloaders may have a commercial relationship with Google” allowing the redistribution I flagged. I emphatically disagree. For one, Google’s Software Principles rules confirm that Google takes a dim view of deceptive bundling: Google requires “upfront disclosure” including “clearly and conspicuously” explaining key functions and advertising, which is missing in the examples above. Google also requires “keeping good company” which requires “not allow[ing] products to be bundled with applications that do not meet these guidelines.” But the bundles at issue include numerous deceptive adware programs. Furthermore, I know of no instance where Google has ever allowed Chrome or any other Google software to be bundled with any adware or other software showing popup ads. Blinkx says it is “quite likely” that Google authorized the installation I flagged. I believe it’s far more likely that Youdownloaders acted without authorization and, indeed, contrary to the Terms of Service that bind every copy of Chrome.

Blinkx consultant E.J. Hilbert purports to have evaluated Blinkx’s practices in search of improprieties. But in describing his methodology, Hilbert says “I have spoken with the Blinkx” staff and managers. Interviews are unlikely to uncover the problems I flagged previously and above. Specifically, Blinkx staff and managers have every reason not to know — and not to want to know — how their affiliates and subaffiliates are getting Blinkx adware onto users’ computers. Nor are Blinkx business records likely to reveal the actions of affiliates and, especially, subaffiliates. The better methodology for investigating such installations is to test live installations on the web, as I did in preparing the installation videos previously and above. Hilbert’s statement gives no indication that he did so.

Hilbert then says that Blinkx’s risk is reduced because “A lot of what blinkx does is … revenue sharing” which he says “takes that ability to hide out of the practice.” I disagree that revenue sharing offers important benefits for the practices at issue. Even if Blinkx pays its distributors and affiliates through revenue sharing, and even if affiliates pay subaffiliates by revenue sharing, the affiliates and subaffiliates still have every incentive to place Blinkx adware on users’ computers without proper disclosure and consent. Revenue sharing in no way dulls the incentive for deceptive installations.

The Applicability and Importance of Zango’s 2007 FTC Consent Order

Blinkx argues at length that Zango’s 2007 FTC consent order does not bind Blinkx. Broadly, Blinkx contends that it “purchase[d] select ex-Zango assets” and that the FTC settlement obligations did not flow with that purchase. A Blinkx attorney even contacted the FTC to seek the FTC’s view. Based on the facts the attorney provided, the attorney reported that an FTC representative stated that he “believes that the Zango consent order might no longer be active or enforceable [on Blinkx] in light on Zango’s bankruptcy.”

I see three reasons why these FTC staff remarks offer Blinkx limited protection. First, as discussed above, the FTC has long held that “buried disclosures” are not sufficient. Zango settlement or not, Blinkx is bound by generally-applicable law, and Blinkx and its partners are using exactly the “buried disclosures” that the FTC has criticized, disallowed, and even brought suit to prevent.

Second, there is good reason to doubt that Blinkx only acquired “select assets” from Zango. In 2009, Zango then-CTO Ken Smith was surprised to see news articles saying that Blinkx acquired “only ten percent” of Zango’s assets, which prompted him to write a piece unambiguously entitled “Blinkx acquired 100% of Zango’s assets.” Smith continued: “[T]he banks have nothing left of Zango’s which they can sell. Blinkx owns it all.” Indeed, Blinkx clearly received the ex-Zango client-side software (adware), the server-side software (receiving information about users’ browsing and selecting and sending ads), the mechanism used to sell the ads (including receiving advertisers’ requests and offers, and collecting payment), Zango’s contractual relationships with advertisers, and Zango’s installed base (computers with Zango adware, which continued showing ads for years). Blinkx’s admittedly “hired select ex-Zango staff.” Blinkx also retained Zango’s headquarters at 136th Place SE Bellevue WA. Apropos of Smith’s message, one might ask: What assets of Zango did Blinkx not acquire? If in fact Blinkx acquired the entire Zango adware business, or substantially all of it, the FTC consent order may well follow the acquisition — as the FTC has repeatedly and successfully argued in other matters.

Third, as Blinkx’s attorney explains in detail, FTC staff specifically refused to offer any official or binding endorsement of Blinkx’s practices — making their informal oral comments non-binding and by all indications not intended for reproduction or redistribution. That’s entirely appropriate, as the FTC is in no position to judge Blinkx’s practices based solely on supposed facts provided by Blinkx; any evaluation would require that the FTC perform its own investigation of Blinkx’s practices and Blinkx’s relationship to Zango. Pending such an evaluation, it’s too soon to say how the FTC would view Blinkx’s activities.

In a further attempt to distance itself from Zango and Zango’s consent order, Blinkx argues that “current practices bear no relation to the ex-Zango practices that led to FTC action in 2006.” In this regard, I urge rereading the FTC’s complaint. In relevant part (emphasis added):

10. In numerous instances, Respondents, through affiliates and sub-affiliates acting on behalf and for the benefit of Respondents, bundled Respondents’ adware with purportedly free software programs (hereinafter “lureware”), including without limitation Internet browser upgrades, utilities, screen savers, games, peer-to-peer file sharing, and/or entertainment content. Respondents, through affiliates and sub-affiliates, generally represented the lureware as being free.

11. When installing the lureware, consumers often have been unaware that Respondents’ adware would also be installed because that fact was not adequately disclosed to them. In some instances, no reference to Respondents’ adware was made on the website offering the lureware or in the install windows. In other instances, information regarding Respondents’ adware was available only by clicking on inconspicuous hyperlinks contained in the install windows or in lengthy terms and conditions regarding the lureware. Because the lureware often was bundled with several different programs , the existence and information about the effects of Respondents’ adware could only be ascertained, if at all, by clicking through multiple inconspicuous hyperlinks. …

13. Respondents knew or should have known that there was widespread failure by their affiliates and sub-affiliates to provide adequate notice of their adware and obtain consumer consent to its installation. …

The preceding examples demonstrate substantially the same problems — “lureware” distributed “through affiliates and subaffiliates acting on behalf and for the benefit of” Blinkx, with “information regarding [Blinkx’s] adware available only by clicking on inconspicuous hyperlinks.” Though seven years old, the FTC’s complaint remains a fine summary of the installation practices at issue. Even if the 2007 consent order does not bind Blinkx, the same concerns — and the FTC’s generally-applicable principles — make Blinkx’s current practices deficient.

Monitoring and Retransmitting Users’ Otherwise-Secure Activities

Blinkx adware observes users’ browsing on all web sites, including sites that employ HTTPS encryption to protect users’ activities from outside examination and interference. Because Blinkx adware runs on users’ computers, HTTPS over-the-wire encryption offers no protection against Blinkx adware examining users’ behavior.

In addition, Blinkx retransmits portions of users’ behavior in cleartext. For one, as users browse, Blinkx sends messages to its control server — obfuscated but by all indications unencrypted. In the excerpted packet log below, see the transmission highlighted in blue, showing the HTTP POST parameter with name epostdata. (Historically, Zango transmitted user activity in clear text in an otherwise-similar method. Example with the relevant transmission marked in yellow.)

Blinkx then also often sends users’ activity details to advertisers. At this stage, the information is neither encrypted nor obfuscated.

For example, in February 2014, I logged in to Google (activating Google’s encryption of all communications between my computer and google.com), then ran a Google search for “cheap flights.” A moment later, Blinkx adware opened a popunder to an advertiser, sending the advertiser the HTTP querystring parameter “FpSub=cheap*flights” (red highlighting below). That transmission exactly revealed the term I had specified in my Google search just seconds earlier, even though my communications with Google were encrypted by HTTPS. See a screen-capture video (confirming the search and encryption) and the unexcerpted packet log (showing the excerpt in context).

POST /showme.aspx?ver=1.0.13.0&pkg_ver=1.0.13.0&rnd=4 HTTP/1.1…

Host: desktopweatheralerts02.desktopweatheralerts00.desktopweatheralerts.com

epostdata=3C60DF491BE019B6857A89B458345C791FF11C4C55E6FC8FB35987CBC1557D1A339623137547FD6C6654CADA9

75131C409FEB9283395BC919707E551027AD090D6091FDFDE98B8BC61B2A63BC53BDC0D1A1ADE3EA8E1D435FC9374A6E997

F16441108EE76153B6FF686FA7C387F36A3E6538ACA30A45DAEC602EC8379A646B307816D825731D8BEAF003EBAD78B9EA2

A50CC41CA8EC06475D89787EFF6D0CBEB614EBDAA642EF628E75B3B7CEE67D329ED0473A25A0B7658708DCDC78D38D64BC7

74979FF5C790B07498F427D6B7A6D7927358BB31D04D483853190ED3DF2624C6D2F5AF8220A09F4C8127506DB58127365CE

7E802385F209311D4176B926D3F2E135AA5A5A72EA88612B9CB5E4E2955F9684E8BFC70139E0CEA582190542B6C9477E912

CEB505940E42AB3C80623ECFF21599AFE3D533B7A4DE8589D178EB996CE29ECD8142D8C91DFD04FA739E19D2EA7179332CB

4E6F28E695A9DA14D45291FFA2289AB24FD4909E542A580397EB75FDFAA834B948596773EB7D306951070937A2DBBB659D6

DBD3F5A4AA893701D83D06825BFB2E332F153DA37745838917237A0C274684F2A04BA80F5AD7EA8523471079417CBB29781

B24DB8869B348CD2FB99CB3AD5A0249FF2407EB276AC0F7776558066304BF116CFC3FC4056B562306DBB4858E77A85AC879

030CB25AEE366703094802AC31A0C8A7495F1D6B07CBDFAC98A59224179D8974C6A184BF7B362040DF1CE0C8FA79D248186

C070053E6E43996407780AFAF7645A733D0717AC6A9E4689C2EEBAFE5E6E600028CDD0BA335C25966A0ABF37B32CCBBCC88

652143BF54BB42B5EB7E526D6BF7C2498F8822D9ED02086ACC723278085A6C006716ABF0CD31205D3A02366C093BE47ED7E

1A8082221B214DFE78D2CFE2385AFB9D85D37CEE076B3109A893C6AF6AA72EE9CF948309C67F83CA8E530324A&data1=01z

M8fY4Pjz%252f2eU5ykwF2WKD4i7vOGf68ZAm01xPGNy3gRrwg5yCweqAgVctm%252b%252bHrHyyVbCqMA28GARV3CugCWKBRv

vJ%252fiQlc%252fSNrRTQniqjqRsrvi%252bw6nUKG4H8sCmoP3IHVih35aSM%252fudbeHi7I9qm6klVmnAT%252f2RFapa9M

BdDXqh4gaVDLu9diOq10N087NnPOZE3nifYHj4Srml9uhiMVE%252fnWdMC0%252fIBwfwb9IhWLsry9YfiN5V99aRmPuoZPn6P

VkIUJ%252bPHs3MGPvKhpusNdr3uR%252bDHkugiVcvIxGi3%252fM%252fGPaE%252bacpY%252bIfaBhJOd315OhlKnz12qRr

HvXydyGcGx%252bt5VkEEz3EiRYinWKwd7wSHfzykYYzwn1DwkfK%252fmfH1pRwsSqvHDCu0gNRsAoX3HqntELdq9OKMIRj%25

2bf5WxZ9HLUTPGibPFT%252bXRsltoAvlY3tl2pENhtkAXUCnx7xNiMjp6wG2y9W7gsDwtKnc7bvyGgM2kkZKE4iwCakYlz9S79

pWl%252bps0IrBMJfLWUx%252fy9JyjBJgdNu0IstCUCPYJvVyA0bzV%252f4kQBybB8%252bOS2wwytiKnpksJNRUNIvRXNzUK

7%252bQunQ6h3gXYFdGhEKdo7glYoivxcyIbL65Z4oze8kx0NM%252fADCXnbkqWNnf8pmZuhpR5L2kVzzZno6p6G78wAJGsZAo

gxRkwVIDvdENnwhDT104NSXao2hwHCUbQ7nFqBfz%252fjf9k0v1Go%252fSLxoHUqkgCCfIrbbd42zygfL24YiHnbFghx4OGcm

UyADk113wYAu7misrVBRGzazaD5zc%252bZqA%252bxWnjiwJF7nOFmO4mC7PGXXSSrZhdqXL6uRbe%252fidiAaQwqB36HuWtG

unkY72K9HwZwViJmaL4rsM28ETJUS9NbU4jESsfnBTZIH%252faViCk7GJnRAgNa3iFo8v9iVrZFtAAzi5%252b%252fWSciE26

ro8rUrZr%252f5iQVyHfGOxgjG1Cc%252btoObB0urQVg48AbuPadcj961p9VYedUrzolNHppRtrTUzyV9%252bLGfn1sUlNRph

ny8oEmlx5GBEs76TVXJBwKju%252fpjUrh1zEESuWrPNUuj3gnhqEUXLdwE7VwpQHPN6P71jRNoAKuZ6QvDOSVJ535pnnz9fAul

ImnnMHDFIiXIhycR7P7ml%252f8Z5Fa8eN0Ac1p%252fCDRnytskpOq8gtSnF3e%252bQdgYwz%252bH4a9mogkR9wio61qpAB%

252fKDKy2xibksTPZfYePBJwGHwWpsH4QNZ2f7yyVanzQAXrGtvUQ0OwkPWlt%252f7aKQw6jkpUfHS8A2hnX0CHI%252fr6Z%2

52fjqMHZWwltzVV00EhAxjxVxXdwn0Ftq5aCbsbUw6RDg0sd14tR5WZYbDyB0HUsI2WRqoEeGvkrN6%252fbvG2SFNll1OcCgJG

Lj2SM6Y8A6C6iSRyIohSuQCqaWC56IGpzenoIO19lPcbUHGrTeYJr14tWuKIIhK6%252fTzhthHEQFqfTQ2BSmt6M2i3Q4k7UX%

252f0FDMrd4Dmt7Kx%252furspSkRzIIARn5QIYTWnvB17Z9l300IiZXVztaget rfwQpF2Ye11Ghzl1jB8A1NrKLSuK5azFl12D8Pb

qDMrXIQe0C4SgPedcWnxOIixma%252f5fEJJ%252fYPIvaVspXlwALzmmcYtB3JbxCLiBzEGLvau0dzfuisHn4IOkJGKr%252fP

7mycLRIdHyZltWCdYTTZSkIRgrX5VQAnHiSqJB8UuV%252bUQ4smjGzcb5JOCs9D9qu8P%252fis5qAblTVkxp5cwTQHOv9zUz6

FMwOAHkDu50T4jIXm0FKtvFF7E%252bkl2zCJHXPg%252b80FUt6LBLCrMn%252bRiSC3vq01SbhLGuhpRPCJSIlBXUzbwFFGkI

QmnG%252b2D3S%252fC7tJzJ40kZhazr89%252fEPRK94Sz0OT7JRDLH%252bzlruvZnsC9MQ4HlaPxU69ssxu32Fli6fb228zS

2mkDQOLJ%252beAC7ygJ6kmeMRf2vXLdas28%253d

HTTP/1.1 200 OK…

ad_url: <input id=ad_url name=ad_url value=http://www.cheapoair.com/?FpAffiliate=Zango&FpSub=cheap*flights><br> …

—

GET /?FpAffiliate=Zango&FpSub=cheap*flights HTTP/1.1 …

Host: www.cheapoair.com

HTTP/1.1 200 OK …

Google goes to great lengths to keep users’ searches confidential, including devoting additional server capacity and electricity to the required encryption. Blinkx defeats those efforts by interceding at the user’s computer and retransmitting a portion of users’ search terms unencrypted, in plaintext. Blinkx’s interception and retransmission allows users’ activities to be observed by anyone along the way, including by other users of the same wifi hotspot.

The FTC has previously filed suit against companies whose desktop software revealed communications through broadly similar design flaws. In 2010, I reported college savings service Upromise transmitting users’ activity in cleartext, even when sites used HTTPS to attempt to keep that information confidential. In response, the FTC brought a complaint against Upromise. In count 1, the FTC expressed concern that Upromise collected “information consumers provided in secure sessions when interacting with third-party websites.” To my knowledge, Blinkx’s data collection is a notch less aggressive than Upromise: Upromise collected credit card numbers, social security numbers, and more, whereas in my testing Blinkx largely collects and retransmits search terms and domain names. But the same principle holds, and the plain language of the FTC’s complaint indicates well-justified concern at client-side software collecting (and insecurely retransmitting) information that users had transmitted with the benefit of encryption.

Incidentally, the green highlighting above shows that when Cheapoair receives traffic from Blinkx, it labels the traffic as coming from “Zango.” Consistent with my longstanding experience, this indicates that Cheapoair, an ex-Zango advertiser, was automatically transferred to Blinkx.

Deceptive Popup Ads

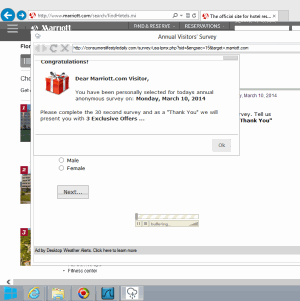

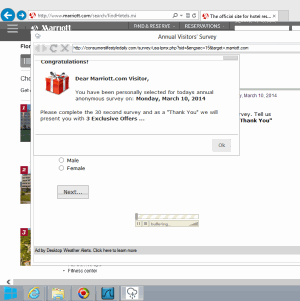

Blinkx adware presents a deceptive ad falsely claiming “You have been personally selected for todays annual anonymous survey” (s.i.c.).

Blinkx adware presents a deceptive ad falsely claiming “You have been personally selected for todays annual anonymous survey” (s.i.c.).

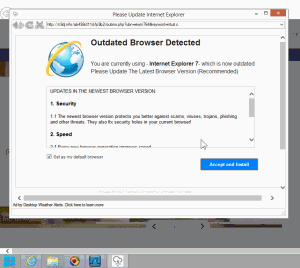

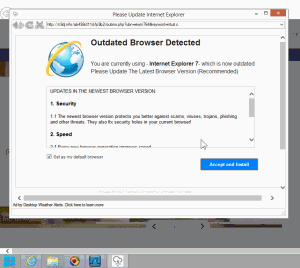

Blinkx adware presents a deceptive ad falsely claiming a user’s browser needs updating.

Blinkx adware presents a deceptive ad falsely claiming a user’s browser needs updating.

Once installed, Blinkx adware shows deceptive ads. For example, in testing on March 10, 2014, Desktop Weather Alerts used the Blinkx adware engine to present a Consumerslifestyledaily .com popup claiming “You have been personally selected for todays annual anonymous survey” (s.i.c.). See top screenshot at right. Because Blinkx told Consumerslifestyledaily .com the domain name of the site I had been viewing, the popup mentioned the name of that site — making the popup look more like a genuine part of the site, even though the site had nothing to do with the popup and indeed is a victim of the popup’s ability to divert and distract its users. Moreover, far from conducting a bona fide survey, the questions actually lead only to a page that attempts to sell the user skincare products and electronic cigarettes — claiming “Your price: $0.00” but adding significant shipping charges.

Similarly, in testing on March 9, Blinkx adware delivered a N9dj.info popup claiming “Outdated Browser Detected” (screenshots: 1, 2). The popup used the distinctive Internet Explorer logo and even delivered an installer called Internet_Explorer_Setup.exe. Despite the “Internet Explorer” label, the popup attempted to install an adware bundle, not Internet Explorer. Moreover, the popup falsely claimed “You are currently using Internet Explorer 7 which is now outdated,” when in fact I was browsing using Windows 8 which came with Internet Explorer 10.

In critiquing Fast Media Converter’s installation of Blinkx adware above, I noted its deceptive ads: claiming a “New Version Available” and using the Chrome name and logo, claiming “your Video Player has a faster version available” and using the Internet Explorer name and logo, and claiming “Outdated Browser Detected” and repeatedly using the Internet Explorer name and logo.

Only because of Blinkx are these advertisers able to interrupt users’ browsing to display their deceptive offers. Consider: I received these popups while browsing well-known trusted sites that would never accept such deceptive advertising. But Blinkx has no such standards.

Defrauding Affiliate Merchants (this section co-authored with Wesley Brandi)

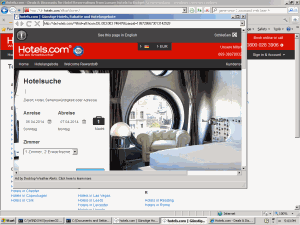

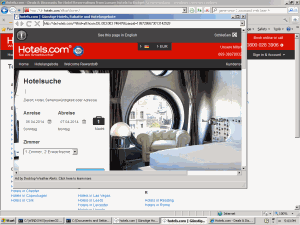

Blinkx and a rogue affiliate charge Hotels.com for traffic it would otherwise receive for free.

Blinkx and a rogue affiliate charge Hotels.com for traffic it would otherwise receive for free.

My January posting flagged Blinkx defrauding affiliate merchants by loading popups that promote the very merchants users are already visiting — thereby claiming commission on users that the merchants had already reached via other methods. I noted that these practices can be difficult for merchants to detect: Standard measurement systems report a high volume of sales, hence seemingly-effective ad campaigns, and the measurement systems fail to alert merchants that this is traffic they would otherwise receive without charge.

To demonstrate the scope of the problem, Wesley and I today post ten more examples showing widespread affiliate fraud.

These incidents weren’t hard to find: Wesley and I built automation that runs many adware programs (not just Blinkx) to protect our advertiser and ad network clients. Our automation found all these examples (and plenty more) in one 12-hour run. Indeed, in the course of a typical month, we regularly alert our clients to a dozen rogue affiliates using Blinkx adware, making Blinkx adware among the most frequent sources of prohibited affiliate traffic draining our clients’ budgets.

| # |

Date |

Traffic origin |

Intermediary domains |

Network |

Victim merchant |

Notes |

Details |

| 1 |

April 4, 2014 |

Blinkx adware |

Statsad, Bdpromocodes |

Tradedoubler |

Expedia UK |

Referer faking |

screenshot, packet log |

| 2 |

April 4, 2014 |

Blinkx adware |

Trackmyads |

Zanox |

Hotels.com |

|

screenshot, packet log |

| 3 |

April 4, 2014 |

Blinkx adware |

Gottemborgcity.blogspot.no |

Tradedoubler |

Hotels.com |

|

screenshot, packet log |

| 4 |

April 4, 2014 |

Blinkx adware |

Dblol, Skyseek |

Zanox |

Ebookers.de |

|

screenshot, packet log |

| 5 |

April 4, 2014 |

Blinkx adware |

Theworldaventure.blogspot.no |

Commission Junction |

Avis |

|

screenshot, packet log |

| 6 |

April 4, 2014 |

Blinkx adware |

Trackmyads, Thequickcoupon |

Commission Junction |

Thewalkingcompany |

Referer faking |

screenshot, packet log |

| 7 |

April 4, 2014 |

Blinkx adware |

Adssend, Eh86, Moreniche |

Commission Junction |

VItamin Shoppe |

|

screenshot, packet log |

| 8 |

April 4, 2014 |

Blinkx adware |

Bit.ly |

LinkConnector |

RingCentral |

|

screenshot, packet log |

| 9 |

April 4, 2014 |

Blinkx adware |

Fluxhub |

Digital River |

Nuance |

|

screenshot, packet log |

| 10 |

April 4, 2014 |

Blinkx adware |

Sale-reviews |

LinkShare |

BH Cosmetics |

Decoy popup and invisible (1×1) IFRAME |

screenshot, packet log |

In response to my evidence of Blinkx and an affiliate improperly claiming commission on traffic Walmart would otherwise receive for free, Blinkx responded that it “specifically prohibits the kind of activity” I presented. But a contract provision is only the beginning. Whatever prohibition may be written in Blinkx’s contracts, we see no sign of Blinkx taking steps to enforce that rule. It would be easy for Blinkx to check whether a Blinkx advertiser is in fact an affiliate and, if so, what network the affiliate is using and what merchant the affiliate is promoting — it could simply load the advertiser’s ad and check for any affiliate link(s). If the affiliate is using a network that has banned adware popups, or promoting a network that has banned adware popups, Blinkx could immediately eject that advertiser. Blinkx could also ban any advertiser that is promoting the same merchant the user is already viewing. Blinkx says it is “always possib[le for an affiliate to] circumvent[] any technical measures that may be put in place” — but there’s no sign that Blinkx has actually established these or other suitable measures. My first article about Zango (then “180solutions”) in 2004 focused on exactly these affiliate frauds, and these practices have continued apace ever since.

Breaking Google’s Rules by Displaying Ads in Popups

Google rules specifically disallow placing Google ads into adware and pop-ups. For example, Google’s AdSense rules specifically disallow “[a]ds in a software application” and “[p]lacing ads in pop-up windows.” I understand that Google’s rules for other search syndicators are broadly similar, although those agreements are not ordinarily available to the public.

Contrary to Google’s rules, Blinkx and its advertisers often load Google advertisements in popup ads. These popups cover other companies’ sites and interrupt users’ browsing. The effects on advertisers are particularly negative: Advertisers pay full price for a Google click that is supposed to be top-quality, but they receive the inferior quality and brand tarnishment of placement in a pop-up ad.

Blinkx presents Google ads in an adware popup.

Blinkx presents Google ads in an adware popup.

The money trail – how funds flow from advertisers to Google to Blinkx adware.

For example, in testing last month, other adware (installed in a bundle along with Blinkx) opened a popup that presented a supposed survey from Websurveypanel.org. (This page was deceptive for other reasons that I won’t explore here.) Blinkx noticed that traffic and opened a popup to Eboom.com with a supposed user search term (“q=”) parameter referencing “websurvey.” Eboom then presented a page of Google ads, with four oversized Google ads and no other content visible in the window. I clicked the first ad and was taken through a Google pay-per-click link to the advertiser, Snapsurveys.com. By all indications, Snapsurveys paid a pay-per-click advertising fee for my visit. Screen-capture video and packet log.

One might ask why Google would allow a partner like Eboom, which buys traffic from adware like Blinkx. But Google does not work with Eboom directly. Rather, the packet log reveals Eboom using Blucora/InfoSpace (an aggregator of subsyndicators) to access Google’s advertising network. I’ve repeatedly flagged tainted InfoSpace traffic, including deceptive toolbars and multiple adware applications. In 2010, I summarized and consolidated my prior findings about InfoSpace, concluding that “InfoSpace hardly appears a sensible partner for Google and the advertisers who entrust Google to manage their spending.” I stand by that conclusion. Indeed, I’ve recently collected ample additional evidence, including proof of InfoSpace sending Google various traffic from other adware beyond Blinkx and through numerous brokers beyond Eboom. (I’ll post other examples when time permits.)

The complexity of the relationship — traffic flowing from Blinkx to Eboom to InfoSpace to Google to advertisers — reveals why advertisers and even Google struggle to put an end to these practices. Yet the complexity is of Google’s own creation, resulting from Google’s decision to let InfoSpace subsyndicate Google’s ads to other partners Google fails to rigorously supervise. Importantly, Google engineers could detect such placements through suitable automation. By 2005, I had already built a crawler to inventory Zango (then 180solutions) advertisements and to determine the ad networks funding Zango. With a similar crawler today, Google could readily identify sites that impermissibly buy traffic from Blinkx — then eject all such sites from the Google syndication network.

Next Steps

I previously suggested that Blinkx disclose its revenue from adware, as distinguished from its other lines of business. My rationale: Of the adware vendors known (from their statements and investor statements) to have received venture capital funding, many or most have ceased operations, and in several instances publicly-available documents indicate that investors received little or no return of capital (not to mention profit). Meanwhile, industry experts widely report that Blinkx is importantly reliant on adware: For example, in a blog comment in March 2014, Zango ex-CTO Ken Smith remarked that “It was my understanding that for a while, the majority of their money was being made off the Zango technology and audience.” (Smith also noted that only “recently” did Blinkx disable the last of the Zango adware clients — entirely consistent with the test installations in my lab.)

In a particularly spirited section of its reply, Blinkx declined to provide the revenue apportionment I suggested. Rather, Blinkx said it “places equal importance on all of its product lines and acquisitions.” I credit Blinkx’s argument that it “is under no obligation to expend resources and energy to detail information beyond its regulatory requirements.” Yet my suggestion has an undeniable appeal. If adware is in fact small, then Blinkx could address investors’ concerns by showing the size of this business. Conversely, failure to provide such proof reinforces my suspicion — and Ken’s! — that adware is and has been a significant revenue source for Blinkx. Meanwhile, Blinkx’s approach also strengthens the inference that adware is significant: If adware were not important to Blinkx, shrewd managers would have elected to discard this controversial business years ago.

Meanwhile, I’ve gotten back in touch with other computer security researchers who have found other deceptive installations of Blinkx adware. We used to write articles about adware weekly, but we’ve subsequently largely moved on to other things, and it takes a while to resuscitate the prior spirit of testing and exposition. Nonetheless, I expect more reports from others in due course.

Looking at Blinkx’s practices as a while, it is striking to see Blinkx paying distributors to put its adware on users’ computers without the hard-fought protections the FTC previously demanded of Zango. Seven years ago, Zango promised to cease these practices, and it paid a multi-million dollar fine to disgorge a portion of its ill-gotten gains. Facing equally brazen conduct continuing after that consent order, the FTC should demand even more far-reaching remedies here.

My testing of Blinkx ex-Zango adware began in 2004 with unpaid writing on my web site, and has grown to include paid and unpaid work for advertisers, ad networks, publishers, investors, and regulators. However, none of these requested or funded this article or any portion of the research presented in this article.