I’ve repeatedly reported improper placements of Google ads. In most of my write-ups, the impropriety occurs in ad placement — Google PPC ads shown in spyware popups (1, 2, 3, 4), in typosquatting sites (1, 2), or in improperly-installed and/or deceptive toolbars (1, 2). This article is different: Here, the impropriety includes a fake click — click fraud — charging an advertiser for a PPC click, when in fact the user never actually clicked.

But this is no ordinary click fraud. Here, spyware on a user’s PC monitors the user’s browsing to determine the user’s likely purchase intent. Then the spyware fakes a click on a Google PPC ad promoting the exact merchant the user was already visiting. If the user proceeds to make a purchase — reasonably likely for a user already intentionally requesting the merchant’s site — the merchant will naturally credit Google for the sale. Furthermore, a standard ad optimization strategy will lead the merchant to increase its Google PPC bid for this keyword on the reasonable (albeit mistaken) view that Google is successfully finding new customers. But in fact Google and its partners are merely taking credit for customers the merchant had already reached by other methods.

In this piece, I show the details of the spyware that tracks user browsing and fakes Google PPC ad clicks, and I identify the numerous intermediaries that perpetrate these improper charges. I then criticize Google’s decision to continue placing ads through InfoSpace, the traffic broker that connected Google to this click fraud chain. I consider this practice in light of Google’s advice to advertisers and favored arguments that click fraud problems are small and manageable. Finally, I propose specific actions Google should take to satisfy to prevent these scams and to satisfy Google’s obligations to advertisers.

Introducing the Problem: A Reader’s Analogy

Reading a prior article on my site, a Register discussion forum participant offered a useful analogy:

Let’s say a restaurant decides [it] wants someone to hand out fliers … so they offer this guy $0.10 a flier to print some and distribute them.

The guy they hire just stands at the front door and hand the fliers to anyone already walking through the door.

Restaurant pays lots of money and gains zero customers.

Guy handing out the fliers tells the owner how many fliers were printed and compares that to how many people bring the fliers into his restaurant.

The owner thinks the fliers are very successful and now offers $0.20 for each one.

It’s easy to see how the restaurant owner could be tricked. Such scams are especially easy in online advertising — where distance, undisclosed partnerships, and general opacity make it far harder for advertisers to figure out where and how Google and its partners present advertisers’ offers.

Google and Its Partners Covering Advertisers’ Sites with Spyware-Delivered Click-Fraud Popups

The money trail – how funds flow from advertisers to Google to Trafficsolar spyware.

In testing of December 31, 2009, my Automatic Spyware Advertising Tester browsed Finishline.com, a popular online shoe store, on a virtual computer infected with Trafficsolar spyware (among other advertising software, all installed through security exploits without user consent). Trafficsolar opened a full-screen unlabeled popup, which ultimately redirected back to Finish Line via a fake Google PPC click (i.e., click fraud).

My AutoTester preserved screenshots, video, and packet log of this occurrence. The full sequence of redirects:

Trafficsolar opens a full-screen popup window loading from urtbk.com, a redirect server for AdOn Network. (AdOn, of Tempe, Arizona, first caught my eye when it boasted of relationships with 180solutions/Zango and Direct Revenue. NYAG documents later revealed that AdOn distributed more than 130,000 copies of Direct Revenue spyware. More recently, I’ve repeatedly reported AdOn facilitating affiliate fraud, inflating sites’ traffic stats, and showing unrequested sexually-explicit images.)

AdOn redirects to eWoss. (eWoss, of Overland Park, Kansas, has appeared in scores of spyware popups recorded by my testing systems.)

eWoss redirects to Netaxle. (NetAxle, of Prairie Village, Kansas, has also appeared in numerous popups — typically, as here, brokering traffic from eWoss.)

Netaxle redirects to dSide Marketing. (dSide Marketing, of Montreal, Canada, says it provides full-service SEO and SEM services.)

dSide Marketing redirects to Adfirmative. (Adfirmative, of Austin, Texas, promises “click-fraud protected, targeted advertising” and “advanced click-fraud prevention.”)

Adfirmative redirects to Cheapstuff. (Cheapstuff fails to provide an address on its web site or in Whois, though its posted phone number is in Santa Monica, California. Cheapstuff’s web site shows a variety of commercial offers with a large number of advertisements.)

Cheapstuff redirects to InfoSpace. (InfoSpace, of Bellevue, Washington, is discussed further in the next section.)

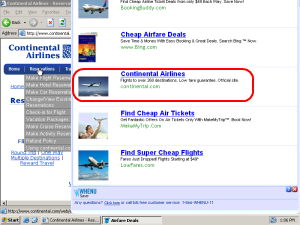

InfoSpace redirects to Google, which redirects through DoubleClick and onwards back to Finish Line — the same site my tester had been browsing in the first place.

This placement is a bad deal for Finish Line for at least two reasons. First, Google charges Finish Line a fee to access a user already at Finish Line’s site. But that’s more of a shake-down then genuine advertising: an advertiser should not have to pay to reach a user already at its site. Furthermore, Google styles its advertising as “pay per click”, promising advertisers that “You’re charged only if someone clicks your ad.” But here, the video and packet log clearly confirm that the Google click link was invoked without a user even seeing a Google ad link, not to mention clicking it. Advertisers paying high Google prices deserve high-quality ad placements, not spyware popups and click fraud.

Finally, the popup lacks the labeling specifically required by FTC precedent. Consistent with FTC’s settlement in its Direct Revenue and Zango cases, every spyware/adware popup must be labeled with the name of the program that caused the popup, along with uninstall instructions. Furthermore, the FTC has taken an appropriately dim view of advertising software installed on users’ computers without user consent. But every single Trafficsolar installation I’ve ever seen has arrived on my test computers through security exploits, without consent. For these reasons, this Trafficsolar-Google popup clearly falls afoul of applicable FTC requirements.

Critiquing InfoSpace’s role

As shown in the prior section and diagram, traffic flows through a remarkable seven intermediaries en route from Trafficsolar spyware to the victim Google advertiser. Looking at such a lengthy chain, the problem may seem intractable: How could Google effectively supervise a partner’s partner’s partner’s partner’s partner’s partner’s partner’s partner? That insurmountable challenge is exactly why Google should never have gone down this path. Instead, Google should place ads only through the companies with which Google has direct relationships.

In this instance, when traffic finally gets to Google, it comes through a predictable source: InfoSpace. It was InfoSpace, and InfoSpace alone, that distributed Google ads into the morass of subsyndicators and redistributors detailed above.

Flipping through my records of prior InfoSpace observations, I was struck by the half-decade of bad behavior. Consider:

June 2005: I showed InfoSpace placing Google ads into the IBIS Toolbar which, I demonstrated in multiple screen-capture videos, was arriving on users’ computers through security exploits (without user consent). The packet log revealed that traffic flowed from IBIS directly to InfoSpace’s Go2net.com — suggesting that InfoSpace had a direct relationship with IBIS and paid IBIS directly, not via any intermediary.

August 2005: I showed InfoSpace placing ads through notorious spyware vendor Direct Revenue (covering advertisers’ sites with unlabeled popups presenting their own PPC ads). The packet log revealed that traffic flowed from Direct Revenue directly to InfoSpace — suggesting that InfoSpace had a direct relationship with Direct Revenue and paid Direct Revenue directly, not via any intermediary.

August 2005: I showed InfoSpace placing ads through notorious spyware vendor 180solutions/Zango. The packet log revealed that traffic flowed from 180solutions directly to InfoSpace — suggesting that InfoSpace had a direct relationship with 180solutions and paid 180solutions directly, not via any intermediary.

February 2009: I showed InfoSpace placing Google ads into WhenU popups that covered advertisers’ sites with their own PPC ads.

May 2009: Again, I showed InfoSpace using WhenU to cover advertisers’ sites with their own PPC ads, through partners nearly identical to the February report.

January 2010 (last week): I showed InfoSpace’s still placing Google ads into WhenU popups and still covering advertisers’ sites with their own PPC ads.

And those are just placements I happened to write up on my public site! Combine this pattern of behavior with InfoSpace’s well-documented accounting fraud, and InfoSpace hardly appears a sensible partner for Google and the advertisers who entrust Google to manage their spending.

Nor can InfoSpace defend this placement by claiming Cheapstuff looked like a suitable place to show ads. The Cheapstuff site features no mailing address or indication of the location of corporate headquarters. WHOIS lists a “privacy protection” service in lieu of a street address or genuine email address. These omissions are highly unusual for a legitimate advertising broker. They should have put InfoSpace and Google on notice that Cheapstuff was up to no good.

This Click Fraud Undercuts Google’s Favorite Defense to Click Fraud Complaints

When an advertiser buys a pay-per-click ad and subsequently makes a sale, it’s natural to assume that sale resulted primarily from the PPC vendor’s efforts on the advertiser’s behalf. But the click fraud detailed in this article takes advantage of this assumption by faking clicks to target purchases that would have happened anyway. Then, when advertisers evaluate the PPC traffic they bought, they overvalue this “conversion inflation” traffic — leading advertisers to overbid and overpay.

Indeed, advertisers’ following Google’s own instructions will fall into the overbidding trap. Discussing “traffic quality” (i.e. click fraud and similar schemes),Google tells advertisers to “track campaign performance” for “ROI monitoring.” That is, when an advertiser sees a Google ad click followed by a sale, the advertiser is supposed to conclude that ads are working well and delivering value, and that click fraud is not a problem. Google’s detailed “Click Fraud: Anecdotes from the Front Line” features a similar approach, advising that “ROI is king,” again assuming that clicks that precede purchases must be valuable clicks.

Google’s advice reflects an overly optimistic view of click fraud. Google assumes click fraudsters will send random, untargeted traffic. But click-frauders can monitoring user activities to identify the user’s likely future purchases, just as Trafficsolar does in this example. Such a fraudster can fake the right PPC clicks to get credit for traffic that appears to be legitimate and valuable — even though in fact the traffic is just as worthless as other click fraud.

What Google Should Do

Google’s best first step remains as in my posting last week: Fire InfoSpace. Google doesn’t need InfoSpace: high-quality partners know to approach Google directly, and Google does not need InfoSpace to add further subpartners of its own.

Google also needs to pay restitution to affected advertisers. Every time Google charges an advertiser for a click that comes from InfoSpace, Google relies on InfoSpace’s promise that the click was legitimate, genuine, and lawfully obtained. But there is ample reason to doubt these promises. Google should refund advertisers for corresponding charges — for all InfoSpace traffic if Google cannot reliably determine which InfoSpace traffic is legitimate. These refunds should apply immediately and across-the-board — not just to advertisers who know how to complain or who manage to assemble exceptional documentation of the infraction.

More generally, Google must live up to the responsibility of spending other people’s money. Through its Search Network, Google takes control of advertisers’ budgets and decides, unilaterally, where to place advertisers’ ads. (Indeed, for Search Network purchases, Google to this day fails to tell advertisers what sites show their ads. Nor does Google allow opt-outs on a site-by-site basis — policies that also ought to change.) Spending others’ money, wisely and responsibly, is a weighty undertaking. Google should approach this task with significantly greater diligence and care than current partnerships indicate. Amending its AdWords Terms and Conditions is a necessary step in this process: Not only should Google do better, but contracts should confirm Google’s obligation to offer refunds when Google falls short.

I’m disappointed by Google’s repeated refusal to take the necessary precautions to prevent these scams. InfoSpace’s shortcomings are well-known, longstanding, and abundantly documented. What will it take get Google to eject InfoSpace and protect its advertisers’ budgets?

Three years ago, I posted

Three years ago, I posted