In public statements, IronSource promises to "empower software" through "faster" downloads, "smoother" installations, and increased "user trust." It sounds like a reasonable business — free software for users in exchange for advertising.

Yet a closer look at IronSource installations reveals ample cause for concern. Far from facilitating "user trust," IronSource installations are often strikingly deceptive: they promise to provide software IronSource and its partners have no legal right to redistribute (indeed, specifically contrary to applicable license agreements); they bundle all manner of adware that users have no reason to expect with genuine software; they bombard users with popup ads, injected banner ads, extra toolbars, and other intrusions. It’s the very opposite of mainstream legitimate advertising. We are surprised to see such deceptive tactics from a large firm that is, by all indications, backed by distinguished investors and top-tier bankers.

In the following sections, we present two representative IronSource bundles, then offer broader assessments and recommendations.

An IronSource-Brokered "Chrome Browser"

Install a "Chrome Browser" and you wouldn’t expect a bundle of adware. But that’s exactly what we found when we tested an IronSource bundle by that name.

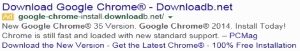

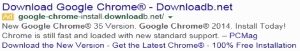

IronSource snares users who are searching for Google Chrome

IronSource snares users who are searching for Google Chrome

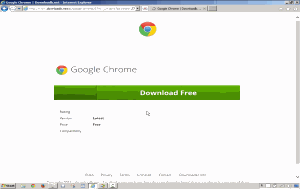

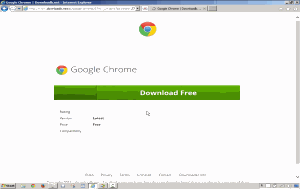

IronSource landing page repeatedly presents Google’s Chrome trademark and logo, giving little indication that users have reached an independent installer.

IronSource landing page repeatedly presents Google’s Chrome trademark and logo, giving little indication that users have reached an independent installer.

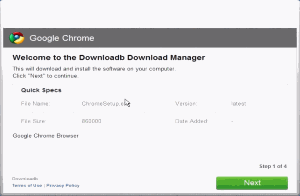

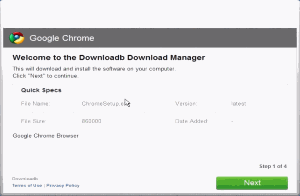

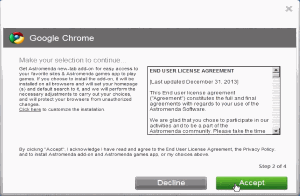

Installer also lacks any branding of its own, giving little indication that users have reached an independent installer.

Installer also lacks any branding of its own, giving little indication that users have reached an independent installer.

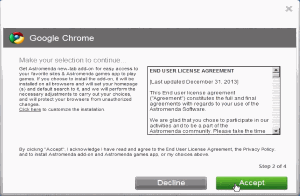

IronSource’s installer presents a series of screens like this, each touting a separate bundled adware program. Eventually a user might notice something amiss — but no "cancel" button lets a user reverse the entire process.

IronSource’s installer presents a series of screens like this, each touting a separate bundled adware program. Eventually a user might notice something amiss — but no "cancel" button lets a user reverse the entire process.

In testing on October 31, 2014, we began with a Google search for "download google chrome." A large ad promised "Download Google Chrome – Downloadb.net" (title) with details "New Google Chrome(R) 35 Version. Google Chrome 2014. Install Today! Chrome is still fast and loaded with new standard support. -PC Mag". Sublinks below the ad elaborated: "Download the New Version – Get the Latest Chrome(R) – 100% Free Installation". Thus, nothing in the text of the ad gives any suggestion that the ad would take a user to a third party rather than to genuine Google software. The display URL, "google-chrome-install.downloadb.net", might alert sophisticated users — but "downloadb.net" is generic enough that the warning is minimal, and bold type focuses attention on "google-chrome" (matching the user’s search terms).

The resulting landing page did not show anything amiss either. The landing page uses Google’s distinctive Chrome icon twice, as well as the large-type label "Google Chrome." On our standard 1024×768 test PC, no on-screen text offered any logo, any company name, or any product name other than Google Chrome.

We clicked the "Download Free" button to proceed, then run the resulting installer. After a perfunctory first screen (still without any affirmative indication that the software is not a genuine Google offering), the installer began to tout third party software. The installation solicitation was strikingly deceptive. First, the window’s two headings were "Google Chrome" and "Make your selection to continue", plus it repeated the distinctive Google Chrome icon at top-left. Notably, no large type indicated that the software is anything other than genuine Google software. Furthermore, the large scroll box on the right offered the bold-type heading "END USER LICENSE AGREEMENT" — more naturally understood to be a EULA for Chrome, the software the user requested and the software the user expected to receive. Small type at top-left mentioned "Astromedia new-tab add-on," but this could easily be overlooked in light of user expectations, prior statements, window headings, icon, and the EULA box heading. Nor did the bottom disclosure cure the problem: The bottom text mentioned Astromedia only in the second line of a disclosure where it is more likely to be overlooked. In addition, the disclosure’s links (to a EULA and privacy policy the user purportedly certifies having read and accepted) lacked any distinctive color or underline, so users are unlikely to recognize them as links. As a result, users have no reason to know that they are (purportedly) accepting lengthy external documents.

Next, the installer pushed another program, "Framed Display." The screen followed the same template critiqued in the prior paragraph, including deceptive headings, deficient disclosures, and unlabeled links. Moreover, the program name "Framed Display" is itself deceptive — a generic name, a combination of two standard words without secondary meaning, which gives no serious indication of the program’s function, origin, or even the fact that it is third-party software unrelated to Chrome.

The installer then touted two further programs, RegClean Pro and DriverSupport. These at least appeared with logos in the top-left, which might help some users realize that they are being asked to install third-party software. But like the prior screens, these both linked to (and asked users to agree to) contracts presented only via links not formatted as such. Both offers still appeared within a window entitled "Google Chrome," continuing the false suggestion that these programs are affiliated with or endorsed by Google.

Seeing the logos for RegClean and DriverSupport, some users might realize that they have received something other than Google Chrome. But the installer lacked a "Back" button to let a user return to prior screens and revoke the acceptances previously (purportedly) granted.

The install video shows the full install sequence, culminating in various popups, new programs, changed browser settings, and other interruptions. The computer becomes noticeably slower, and most users would find the computer much less useful. In fact we found 2,478 new files created as well as 2,465 registry values created — quite an onslaught. Among the most urgent problems is that, as best we can tell, a user cannot remove the DriverSupport’s window from the screen except by killing the process with Task Manager.

In a remarkable twist, the installer pushes the user to install additional software even after the main installation is complete. In particular, after the user receives the four offers described above, the installer runs a 30+ second download of the various programs to be installed. (In the video, this is 1:16 to 1:50.) The user then sees a "Finish" button. But far from ending the installation solicitations, "Finish" brings a solicitation for yet other adware, MyPCBackup. At the conclusion of an installation and after pushing a button labeled Finish, users naturally and reasonably expect only perfunctory final tasks, not requests to install more unrelated advertising software. Furthermore, the on-screen disclosures say nothing of adware, pop-up ads, or tracking of users’ browsing; and the links to EULA and privacy policy again lack any labeling to alert users that they are clickable. On the whole, users are poorly positioned to evaluate this offer, understand what they are asked to accept, or provide meaningful acceptance. Nor is this installer alone in presenting other solicitations after installation; we’ve seen other IronSource installers try the same scheme.

This bundle constitutes both software counterfeiting and trademark infringement. Contrary to the title of the initial ad and the large-type heading in every screen of the installer, this is not the genuine "Google Chrome" installer that Google provides; rather, it’s a wrapper with all manner of other software from third parties unaffiliated with Google. At every step, the installer features Google’s distinctive "Chrome" brand name and logo with no statement that Google authorized their use. And the installer redistributes Chrome despite a clear admonition, within the standard Chrome Terms of Service, that "You may not … distribute … this Content [Chrome] (either in whole or in part) unless you have been specifically told that you may do so by Google… in a separate agreement." The installer offers no suggestion, and certainly no affirmative statement, that Google has provide any such permission. Indeed, in a telling twist, we found that the installer never even showed the Chrome Terms of Service, contrary to Google’s standard requirement (implemented in all genuine Chrome installers) that users accept the ToS before receiving Chrome.

This bundle is also an objectively bad deal for consumers. A consumer seeking Chrome can easily obtain that exact program, on a standalone basis, without any bundled adware, toolbars, popups, injections, or other extra advertising or tacking. The installer adds nothing of genuine value to users; it delivers only the software that its adware partners pay it to deliver, and the partners pay to have their software delivered to users only because they correctly anticipate that users would not seek to install adware if it were not foisted upon them.

Although the IronSource company name appears nowhere in the installer’s on-screen displays, numerous factors indicate that this is indeed an IronSource installation. For example, installation temporary files include multiple references to "IC", and registry keys were created within the hierarchy HKEY_USERSSIDSoftwareInstallCore. (InstallCore is the IronSource service that provides adware bundling and adware installation.) Other temporary files were created within folders with prefix "ish******", "is**********", and "is*******", best understood as abbreviations for IronSource. Furthermore, while each installer connected to different hosts to obtain installation components, each installer’s hosts included at least one with an IP address used by IronSource (according to standard IP-WHOIS). Host names followed a pattern matching longstanding IronSource practice (as previously reported by, e.g., Sophos), including hosts called cdneu and cdnus, exactly as Sophos reported.

Moreover, it seems that some of the bundled adware is itself made by IronSource. For example, the Astromenda browser plug-in stores its settings in a Windows Registry section entitled SoftwareInstallCore — a fact most logically explained by Astromenda being made by IronSource’s InstallCore.

The Nonexistent "Snapchat Windows" App that Delivers Only Adware

Snapchat fans often wish for a Windows client. No such software exists, but that doesn’t stop an IronSource bundle from claiming to offer one, and thereby bombarding interested users with a variety of adware.

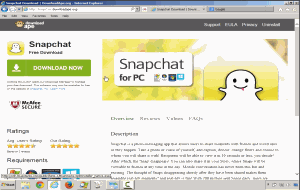

IronSource snares users who are searching for Snapchat.

IronSource snares users who are searching for Snapchat.

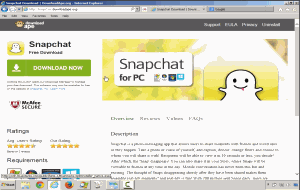

IronSource landing page repeatedly presents Snapchat’s trademark and logo, giving little indication that users have reached an independent installer. In fact there exists no genuine "Snapchat for PC" software, and IronSource’s bundle is most notable for delivering adware.

IronSource landing page repeatedly presents Snapchat’s trademark and logo, giving little indication that users have reached an independent installer. In fact there exists no genuine "Snapchat for PC" software, and IronSource’s bundle is most notable for delivering adware.

In testing, we searched for "Snapchat Windows" and clicked an ad claiming to provide the "Latest 2014 PC version" of "Snapchat." The resulting landing page correctly describes Snapchat but says nothing of any bundled adware. Meanwhile, a prominent "McAfee SECURE" Logo purports to certify the trustworthiness of the site, notwithstanding the problems that follow. (We discuss McAfee’s strange role, both flagging this installation and simultaneously certifying it, at the end of this article.)

We clicked "DOWNLOAD NOW" and proceeded to the installer. The first install screen said nothing of any bundled adware. The subsequent screens (second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth) had the same problems detailed above, including lacking distinctive branding for the unrelated third-party software that’s touted, lacking distinctive format on links to contracts users purportedly accept, and lacking back buttons to serve users who realize something is amiss and want to change their mind. Additional shortcomings in this installation:

- As we repeatedly demonstrated in the install video (1:35 to 1:47, 2:34, 2:47, 3:01), even if a user does click to activate the license, the installer remains superimposed always-on-top in the foreground, thereby blocking a user’s effort to read the document the user is purportedly accepting.

- For one bundled program (video at 2:19 and 2:29), the agreements are hosted on an inoperational server, which completely prevents any attempt to read them.

- The text of the installation disclosures is illogical. For example, the disclosure for MyPCBackup adware advises the user to "Click ‘Play’ on the video to see what MyPCBackup can do for you" — but no video or play button is shown.

This installer bundles even more software than the fake Chrome installer detailed above. We found the fake Snapchat bundling Astromenda, Framed Display, RegClean Pro, MyPCBackup, and Weatherbug.

As far as we can tell, the installer never actually provides Snapchat software. Rather, the installer provides unrelated software called BlueStacks (a program which lets users "install" and use Android apps on Windows PC). It’s no surprise that the installer doesn’t provide a Snapchat Windows app, since none exists. Yet this omission undermines the entire value proposition promised to the user. Notably, BlueStacks is itself freely available, without bundled adware.

Similar Installations

We have seen numerous similar installations. These installs share many factors:

- They grab the attention of users searching leading search engines for common software including popular commercial applications like Adobe Reader, Chrome, Firefox, Flash, Internet Explorer, and Java as well as open source software such as 7zip, GIMP, and OpenOffice.

- Often, the installations significantly overstate the need for the installation or the benefits it can provide. For example, some installation solicitations falsely claim that a media player is out of date or, as in the Snapchat example above, even promise software that does not actually exist.

- They use generic domain names (our examples of downloadb.net and downloadape.org are typical) with no affirmative indication that they are not the official distributors of the specified software. Quite the contrary, their text, images, and layout suggest that they are the authoritative sources for the software they promise.

- They fail to disclose the presence of bundled adware until midway through the download process, and they almost always lack "back" buttons to let a user reverse course once the bundled adware becomes apparent.

- They fail to disclose the true identity of the companies behind the installs, including using domains with limited or no contact information, as well as domain Whois with privacy protection.

Ultimately, these bundled installations provide users with nothing of genuine value beyond the adware-free installs easily available from the original developers. They are a source of widespread user complaints on software discussion forums, as users with so much adware systematically report that their computers are slow and unreliable.

IronSource’s Responsibility

By all indications, IronSource has the right and ability to control these installations. Installation code is obtained from IronSource servers; the installer EXE acts as a bootstrap, downloading configuration and components at runtime. Indeed, the IronSource installer architecture entails all "creative" materials (such as installation text and images) hosted on IronSource servers, letting IronSource easily accept or reject configuration details.

IronSource is likely to blame third party "partners" for most or all of the defects we have listed, but our analysis indicates that IronSource is importantly responsible. First, IronSource’s servers and systems create the installation bundle; IronSource can easily refuse to create deceptive installations, including refusing to create bundles with names matching well-known software such as "Chrome." Moreover, by IronSource’s own admission, its systems select and optimize the offers presented to users: "InstallCore improves install completion rates by about 32%" with "customized installers [that] reinforce branding and user trust," optimized through "the installer A/B testing tool to continuously improve results." IronSource even indicates that its own staff design installations: "Every branded installer is backed by dedicated graphic designers and a team of UI/UX specialists [who] adjust and continually make improvements that drive more installs." And IronSource itself brokers the relationships between "premium advertisers" (making adware) and software publishers using IronSource installers.

Meanwhile, the apps at issue entail self-evident counterfeiting. It is widely known that Google does not allow third parties to bundle its Chrome browser with adware, and that there is no such thing as a Snapchat Windows app. Even the barest of examinations by IronSource staff would have revealed these implausible titles for the respective installers — red flags that the installations are not what they claim to be.

IronSource’s installers are "bootstraps" that check with an IronSource server before beginning an installation. (IronSource explains that its "installation client downloads in real-time a list of offers" to present to a given user.) By removing or modifying installer configuration files on an IronSource server, IronSource can disable any installer it determines to be deceptive or otherwise improper — even months after that installer was created. Thus, IronSource can easily block further installs using the deceptive practices we have flagged here, as well as similar practices by other installers.

Notably, IronSource’s involvement meets the common law tests for both contributory and vicarious liability, wherein a company is liable for the actions of its partners. Contributory liability arises when a company knows of illicit acts and when it assists in those acts. Here, IronSource surely knows of illicit conduct (including counterfeiting) both because it is obvious and because consumers and rights-holders have complained. IronSource’s knowledge of deceptive installation disclosures is even clearer because by all indications IronSource systems optimized or even designed the installation disclosures. As to IronSource’s assistance, note that IronSource helps partners by entering into agreements with adware providers to be paid to install their software, bundling adware into installers, and designing and optimizing installers. IronSource thus satisfies the tests for contributory liability. Meanwhile, vicarious liability arises when a company has the power to prevent illicit acts and when it benefits from those acts. Here, IronSource can stop the deceptive installations because each installation checks with IronSource servers to obtain adware to be presented to users, which gives IronSource with an easy opportunity to disable an installer. IronSource benefits from the installations because it retains a portion of the payment from adware vendors. IronSource thus also satisfies the test for vicarious liability. In addition, of course, IronSource might itself be directly liable for those acts that it does itself, e.g. designing or optimizing deceptive installations.

TRUSTe Trusted Download Violations

IronSource has sought and obtained TRUSTe Trusted Download certification, which claims to assure that software is "safe" so that users "feel more secure" and proceed with installations. Trusted Download requires compliance with numerous rules, and our inspection reveals that IronSource falls short.

For one, TRUSTe Trusted Download rules specifically prohibit "induc[ing] the User to install, download or execute software by misrepresenting the identity or authority of the person or entity providing the software." See rule 14.g. IronSource might argue that if any such misrepresentation occurred, it was made by an IronSource distributor, publisher, or other partner, but not by IronSource itself. But rule 14.j disallows certified software from being included in any bundle with software engaging in violations of any portion of rule 14. So even if it was IronSource’s partners who violated rule 14.g, their violation put IronSource in violation of rule 14.j.

Furthermore, TRUSTe Trusted Download requires disclosures that go well beyond what these installs actually provide. For example, rule 3.a.i.2 requires "prominent link[s]" to all reference notices providing full terms and conditions, whereas the examples above show links not labeled as such (without distinctive color or underlining), and thereby prevent users from recognizing the links as such. We also question whether IronSource partners’ changes of user browser configuration (home page, toolbars, etc.) satisfy the requirement of 3.a.i.1.A-D.

Here too, IronSource might argue that its distributors, publishers, or other partners are responsible for these violations. But Trusted Download rules specifically speak to a company’s responsibility for its partners’ disclosures. See rule 9. Under rule 9.a, IronSource is required to establish contractual provisions in agreements with partners to assure compliance with TRUSTe’s rules. Under 9.d, IronSource must demonstrate to TRUSTe that it has an effective process for assuring compliance. Under 9.e, IronSource must itself monitor compliance and report any known noncompliance to TRUSTe; failure to report is itself a violation.

A further violation comes from IronSource’s detection of virtualization environments where its software may be tested. Trusted Download rule 2.c.viii requires that certified software be compatible with virtualization tools such as VMware to facilitate testing. In contrast, IronSource systematically declines to show adware offers — its raison d’être — when running in virtualization environments. If TRUSTe tested IronSource using VMware, TRUSTe staff would see none of IronSource’s deceptive installation solicitations, and they would reach a mistaken assessment of IronSource’s purpose and effect.

We have forwarded these violations to TRUSTe and urged TRUSTe to revoke the certification of IronSource. Given the nature and scope of the violations, we suggest revocation without permission to reapply. TRUSTe’s distinguished members and Trusted Download founding supporters (including AOL, Verizon, and Yahoo) wouldn’t want to be associated with a company engaged in software counterfeiting, trademark infringement, adware bundling, and the other practices we have presented.

Violations of Other Industry Rules for Software Practices

Beyond TRUSTe, several key firms and industry groups offer standards for software practices. IronSource installations systematically fall short.

For example, Google’s Software Principles require "upfront disclosure" of the programs to be installed and their effects, whereas these IronSource installations disclose the programs one at a time — the very opposite of "upfront." Furthermore, Google’s "keeping good company" principle disallows bundling an app with others that violate Google’s principles and simultaneously blocking any IronSource attempt to deflect responsibility to others. Meanwhile, Google’s AdWords Counterfeit Goods policy prohibits any attempt to "pass [something] off as a genuine product of [a] brand owner," thereby disallowing IronSource installations that claim to be Google, Snapchat, or the like. Google’s AdWords Misrepresentation policy requires that an advertiser "first provid[e] all relevant information and obtain… the user’s explicit consent" (emphasis added) before prompting users to begin a download, whereas these IronSource installations include no such disclosures on landing pages and disclose bundled apps one by one during the installer. Other Google requirements ban deceptive domain names and display domains as well as unauthorized distribution of copyrighted content, which also occur here. We see strong arguments that IronSource installs fall short of each of these requirements.

Microsoft’s Bing has similar Editorial Guidelines, which these installations similarly violate. For example, Microsoft’s intellectual property guidelines disallow promoting counterfeit goods and further disallow copyright infringements (such as redistribution of another company’s software without its permission). Microsoft’s misleading content guidelines prohibit deceptive suggestions about a site’s relationship with a product provided by others and requires an explicit disclosure of that fact. Microsoft further limits use of brands and logos which tend to give a false sense of authorization. Microsoft’s software guidelines add special rules for installations including requirements for the timing and substance of disclosures, and Microsoft specifically bans adding additional software to a package produced by someone else. We see strong arguments that IronSource installs fall short of each of these requirements.

Facing these and other requirements, it’s hard to see how IronSource could claim to comply. In response, Google and Microsoft should ban IronSource from advertising through their respective search engines. They should enforce that ban both through diligent checks and through "cease and desist" orders advising IronSource and its partners and affiliates not to attempt to buy advertising through intermediaries or other company names.

The Role and Responsibility of Investors

IronSource’s efforts to date have relied on significant support from investors. Specific investors apparently decline to be listed (perhaps anticipating unwanted scrutiny like this article). But the Wall Street Journal reports that JP Morgan and Morgan Stanley are serving as bankers and raised $80 to $100 million in August 2014. IronSource reportedly plans an IPO for 2015 with anticipated valuation of $1.5 billion.

We wonder whether investors fully understand IronSource’s activities, users’ distaste for adware, and the lurking risks if users, software rights-holders, search engines, and others seek to block IronSource’s activities. Suppose, for example, that Google banned all IronSource installations from advertising in AdWords — a reasonable decision based on the deceptive installations flagged here. A few large losses like this could put a major crimp in IronSource’s plans.

Interest from investors also opens IronSource to new forms of vulnerability and accountability. A decade ago, notorious adware vendor Direct Revenue succeeded in raising significant funds from investors, some of whom later found their computers running Direct Revenue adware. In a notable email, Barry Osherow of TICC sought personal assistance from Direct Revenue CEO Joshua Abram in removing unwanted Direct Revenue adware. In another, a consumer complained to Insight Partners about their funding of Direct Revenue. Insight’s Ben Levin passed the message on to managing director Deven Parekh who instructed that Insight be removed from Direct Revenue’s web site. Deven specifically worried that “all I need is Bob Rubin getting this email,” referring to the former Secretary of the Treasury who later became a special limited partner at Insight. (These emails and hundreds of others became publicly available when the New York Attorney General sued Direct Revenue and released selected business records.) In my view, these investors were correct to worry that their adware would attract unwanted public scrutiny, and that risk remains for current adware investors.

Co-author Edelman has updated his Investors Supporting Spyware page to list IronSource and known information about its investors and bankers.

Next Steps

IronSource boasts that its installation service "installs better" in that it "improves install completion rates by about 32%." IronSource attributes increased installations to solving technical problems. But another plausible reason for more installs is that IronSource and its partners resort to exceptional deception including disguising their software as coming from others, presenting disclosures that are at best incomplete, and otherwise pushing the limits in foisting advertising software few users would willingly accept. In that context, a higher installation rate is nothing to celebrate; more installs just mean more users infected with unwanted adware.

To bring an end to these practices, a natural first step is to enforce existing rules for advertising standards and practices. Having established Trusted Download to check for this kind of misbehavior, TRUSTe is particularly well positioned to take action based on the violations detailed above. TRUSTe should at least revoke its erroneously-granted certification and perhaps also post an affirmative statement of noncompliance. Google and Microsoft should similarly ban these IronSource installations from their respective search engines.

Computer security companies appear to have at best partial success at detecting both IronSource and the additional programs that IronSource bundlers install. For example, on December 15, 2014, Mozilla blocked the Astromenda Search Addon (included in both bundles presented above) from being installed into any Firefox browsers, reporting that "This add-on is silently installed and is considered malware, in violation of the Add-on Guidelines." That said, IronSource quickly moved to pushing new toolbar, this time labeled Vosteran, with similar functionality. As of the posting of this article, Vosteran has not been blocked by Mozilla. For a broader assessment of security companies’ assessment of IronSource software, we used VirusTotal to check detections of the fake Snapchat installer described above. VirusTotal reported just 14 of 54 security programs detecting it as unesirable software. For example, McAfee detected it, but Microsoft and Symantec did not.

We are particularly struck by McAfee’s inconsistent approach to IronSource software. On one hand, as we note above, McAfee was one of a minority of security vendors that detected IronSource’s fake Snapchat app, so if a McAfee user attempts to install the app, a warning will protect the user. That said, McAfee SiteAdvisor’s online safety tool inexplicably fails to detect downloadape.org, the site hosting the installer. (Disclosure: co-author Edelman previously served as an advisor to SiteAdvisor, but has had no connection to the product or McAfee since 2010.) In addition, as we note above, the fake Snapchat landing page features a prominent "McAfee SECURE" logo which purports to certify the trustworthiness of the site. Once McAfee’s software flagged the app as untrustworthy — correctly, in our view — we think SiteAdvisor’s page should have been updated and any McAfee SECURE certification should have been rescinded.

We and others have been fighting adware for more than a decade. But with capable and well-funded adversaries like IronSource pushing adware through new and creative tactics, there’s ample work left to do.

* – Pat participated as an equal coauthor but prefers to be listed only with his first name.