While claiming price advantages over taxis, Uber overcharges consumers by withholding promised discounts and credits. In today’s post, I examine a set of Uber pricing guffaws — each, a breach of the company’s own unambiguous written commitments — that have overcharged consumers for months on end. Taken together, these practices call into question Uber’s treatment of consumers, the company’s legal and compliance processes, and its approach to customer service and dispute resolution.

A "free ride" or a $15 discount?

Uber offers "free rides" when users refer friends.

Uber offers "free rides" when users refer friends.

Uber specifically confirms that the friend’s "first ride" is free, while the existing user gets "a free ride (up to $15)."

Uber specifically confirms that the friend’s "first ride" is free, while the existing user gets "a free ride (up to $15)."

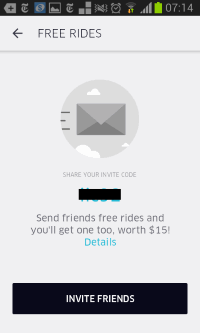

Uber asks existing users to refer friends — promising significant sign up bonuses to both new and existing users for each referral. First, the existing user activates the Free Rides function in the Uber app, revealing the offer and a code that the new user must enter so Uber can track the referral. Quoting from the first screenshot at right (emphasis added):

Share your invite code [placeholder]. Send friends free rides and you’ll get one too, worth $15! Details. INVITE FRIENDS.

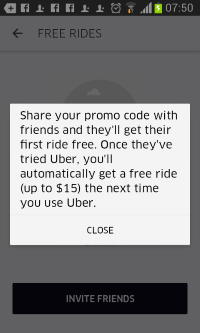

A user who taps "Details" sees two additional sentences (quoting from the second screenshot at right):

Share your promo code with friends and they’ll get their first ride free. Once they’ve tried Uber, you’ll automatically get a free ride (up to $15) the next time you use Uber. CLOSE.

Neither screen provides any menu, link, button, or other command offering more details about other requirements or conditions. The text quoted above is the entirety of Uber’s offer.

Uber’s promise is clear — a "first ride free" for the new user, and a "free ride (up to $15)" for the existing user. But Uber’s actual practice is quite different. Most notably, the new user’s "free ride" is also limited to a $15 discount. One might ask whether the "worth $15" in the first screen applies to the friend’s free ride or to the existing user’s free ride or perhaps both. But the Details screen leaves no doubt that this limitation applies only to the existing user. Notice the placement of the "up to $15" parenthetical only in the sentence describing the existing user’s free ride. In contrast, the separate sentence about the new user’s ride promises "their first ride free" with no indication of any maximum value.

These discrepancies create unfortunate surprises for typical Uber customers. Consider the standard workflow. An existing Uber user tells a friend about Uber and, in person, helps the new user install the app and create an account, including entering the existing user’s referral code when prompted. "You’ll get a free ride," the existing user explains, guided by Uber’s simple on-screen offer. The new user then takes an expensive ride; expecting the ride to be free (as promised), the new user might choose Uber for a distance that would otherwise have been a better fit for a train or bus, or the new user might accept a high surge multiplier. Only later does the new user learn that according to Uber, "free" actually meant a $15 discount. The user would have no written evidence of Uber’s "free ride" promise, which was conveyed orally by the existing user. So the new user is unlikely to complain — and my experience (detailed below) indicates that a request to Uber is unlikely to get satisfaction.

I know about these problems because of an experience referring a friend — call her my cousin — in January 2016. I told her she’d get a free ride, but her receipt showed no such benefit. In fact she took her first ride in another country, which prompted me to check for other discrepancies between Uber’s marketing statements and its actual practice.

Piecing together statements from Uber’s support staff and the various disclosures in Uber’s Android, iOS, and mobile web apps, I found five separate restrictions that were not mentioned mentioned anywhere in Uber’s new user offer as presented to existing Android users:

- The new user’s credit only applies to a ride in the country that Uber designates as the new user’s home country or the currency that Uber designates as the new user’s home currency. But Uber’s signup page doesn’t ask about a user’s home country or currency. As best I can tell, Uber automatically sets a user’s home country based on the user’s IP address or location at the time of signup. (Source: Uber staff indicated that "the promo is currency specific" in explaining why my cousin received no discount on her first ride.)

- The existing user’s credit can only be redeemed towards a ride in the country that Uber designates as the existing user’s home country. (Source: Uber’s iOS app, GET FREE RIDES offer, secondary disclosure screen, stating that "discounts apply automatically in your country," emphasis added.)

- The new user’s maximum ride value varies by country. Not only is there a maximum value (contrary to the simple "first ride free" in Uber’s second screen above), but the maximum value is not mentioned to the existing user. (Source: Uber’s iOS app, GET FREE RIDES offer, secondary disclosure screen; and mobile web, new user offer, page footer.)

- All discounts expire three months from issue date. (Source: Uber’s iOS app, GET FREE RIDES offer, secondary disclosure screen.)

- Offer is not valid for UberTaxi. (Source: Uber’s iOS app, GET FREE RIDES offer, secondary disclosure screen; and mobile web, GET FREE RIDES offer, page footer.)

The table below presents the Uber’s marketing offers in all three platforms, along with the errors I see in each:

| Android | iOS | Mobile Web | |

| Primary disclosure | |||

| Secondary disclosure |

Once they take their first ride, you’ll automatically get your next ride free (worth up to $15). Discounts apply automatically in your country and expire 3 months from their issue date. Offer not valid for uberTAXI. |

||

| Errors |

New user’s ride is actually limited to $15 (or other amounts in other countries). In contrast, both disclosures indicate that there is no limit to the value of the new user’s ride. Discount only applies to a new user’s first ride in the user’s home country as determined by Uber. Existing user’s discount can only be redeemed in existing user’s home country. Discounts for both the new and existing user expire three months from issue date. Offer is not valid for UberTaxi. |

Secondary disclosure plausibly contradicts primary disclosure: Primary disclosure promised "a free ride" for the new user, while secondary disclosure retracts "free ride" and instead offers only a discount. In contrast, FTC rules allow secondary disclosures only to clarify, not to contradict prior statements. Discount only applies to a new user’s first ride in the user’s home country as determined by Uber. |

Discount only applies to a new user’s first ride in the user’s home country as determined by Uber. Existing user’s discount can only be redeemed in existing user’s home country. Discounts for both the new and existing user expire three months from issue date. |

I first alerted Uber staff to these discrepancies in January 2016. It was a difficult discussion: My inquiries were bounced among four different support representatives, with a different person replying every time and no one addressing the substance of my messages. So I reluctantly gave up.

Six weeks later, a different Uber rep replied out of the blue. He seemed to better understand the problem, and I managed to get two separate replies from him. At my request, he committed to "pass this along to the appropriate team." That said, he did not respond to my repeated suggestion that Uber needed to refund affected consumers.

Eight weeks after my final correspondence with the fifth Uber representative and sixteen weeks after I first alerted Uber to the problem, I see no improvement. Uber’s Android app still makes the same incorrect statements about promotion benefits, verbatim identical to what I observed in January.

Credit on your "next trip" — or later, or not at all

Uber claimed I’d get a "credit" on my "next trip." In fact, the credit seems to apply only to a future trip in the same country where the problem occurred.

Uber claimed I’d get a "credit" on my "next trip." In fact, the credit seems to apply only to a future trip in the same country where the problem occurred.

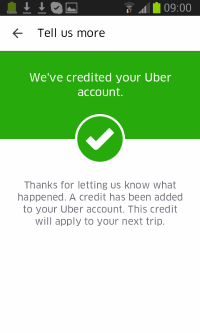

In a variety of circumstances, Uber responds to customer complaints by issuing credits towards a customer’s "next trip." For example, during a recent attempt to ride with Uber in Mexico, I was unable to find or contact the driver. (I was where the on-screen pushpin told me to be, and GPS seemingly told the driver he was where he was supposed to be, but we just couldn’t find each other.) I later received an email receipt showing that I had been charged a cancellation fee. In Uber’s "Help" area, I used Uber’s "I was charged a cancellation fee" feature, and I was immediately advised (emphasis added):

We’ve credited your Uber account. Thanks for letting us know what happened. A credit has been added to your Uber account. This credit will apply to your next trip.

Imagine my surprise when, upon returning to the US a few hours later, I took another Uber ride but received no such credit.

It seems Uber’s notion of credits is in fact country-specific or currency-specific. My problem resulted from difficulty finding a driver in Mexico, where I don’t live and rarely travel. Far from applying the credit on my "next trip," it seems Uber’s systems will carry the credit forward to my next journey in Mexico. (See Uber’s Payment screen, "Credit Balances" section, showing the amount of the cancellation fee as a credit in the currency associated with the country where that fee was charged.) But this is much less useful to users traveling internationally. For example, Uber might impose a time limit on the credit — analogous to Uber’s undisclosed three month limit for use of a "free ride" credit (as revealed in the preceding section). And some users may never return to (or never again take Uber rides in) certain countries or currencies. The plain language of "your next trip" of course purports to protect users against all these contingencies; "your next trip" means a trip denominated in any currency, perhaps soon but perhaps indefinitely in the future. Uber’s actual practice is plainly less favorable to consumers.

Here too, predictable consumer responses increase the harm from Uber’s approach. If a consumer was charged improperly and felt Uber’s response was out of line, the consumer might pursue a credit card chargeback. But when Uber tells the consumer "We’ve credited your Uber account" and "This credit will apply to your next trip," there’s every reason to think the problem is completely fixed. Then the consumer may forget about the problem; certainly the consumer is less likely to diligently check future Uber receipts for a credit that was slated to be automatic and guaranteed. In addition, consumers are vulnerable to the passing of time: If a consumer rides with Uber only occasionally, the permissible time for a chargeback may have elapsed by the time the consumer’s next ride.

Update (May 25, 2016): Four weeks after I reported this discrepancy to Uber, I received a reply from an Uber representative. He confirmed that I did not receive the promised credit for the general reason I described above — a credit provided in one currency, while my next trips was in a different currency. I reminded him that Uber’s statements to users say nothing of any such restriction. I also pointed out that Uber is capable of converting currencies, and I encouraged him to assure that other users, similarly situated, are appropriately refunded. So far as I know, Uber has not done so.

Checking with friends and colleagues, and receiving further reports from strangers, I’ve learned about a fair number of other Uber billing errata. For example, one user confidently reported that when a driver cancels a ride — perhaps seeing a surge in another app, getting lost, learning that the passenger’s destination is inconvenient, or just changing his or her mind — Uber still charges the passenger a cancellation fee. I haven’t been able to verify this, as I don’t have an easy way to cause a driver to cancel. But in the Uber help tool, the "I was charged a cancellation fee" menu offers as one of its preset reasons for complaint "My driver cancelled" — confirming that Uber’s systems charge cancellation fees to passengers when drivers cancel. Of course Uber’s systems can distinguish who pressed the cancel button, plus Uber could ask a driver the reason for cancellation. I see no proper reason for Uber ever to charge a passenger a cancelation fee if it is the driver who elected to cancel.

Users with experience with this problem, or other Uber contracting or billing errata, should feel free to contact me. I’ll add their experiences here or in a follow-up.

Update (June 4): Readers alerted me to UberPool drivers repeatedly charging for two passengers purportedly riding, when only one passenger was actually present, increasing the charge to passengers.

Update (June 4): In federal litigation against Uber, blind passenger Tiffany Jolliff reports that not only did multiple Uber drivers refuse to transport her and her service dog, but Uber charged her a cancellation fee each time a driver refused to transport her.

Lessons from Uber’s billing errors

I see four distinct takeaways from these billing errors. First, Uber’s engineering, testing, and legal teams need to sharpen their focus on billing, promotions, and credits. The coding of a promotional offer is inextricably linked to the marketing text that describes the offer. Similarly, the coding of a customer service benefit must match the text that explains the benefit to users. Both should be checked by attorneys who specialize in advertising law and consumer protection. Instead, in the problems I described here, Uber’s billing logic seems to be entirely separate from the text presented to consumers. It is particularly striking to see Uber’s three separate textual descriptions of the new user promotion — all three of them incorrect, yet in three different ways. Even a basic attorney review would have flagged the discrepancies and identified the need to inquire further. An advanced attorney review, fully attuned to FTC disclosure rules, might also question what appears in the primary disclosure versus the secondary disclosure. Attorneys might reasonably caution Uber against repeatedly and prominently promising "FREE RIDES" when the company’s actual offer is a discount.

Second, Uber’s overcharging is both large and long-lasting. I reported the new user promotion problems in January 2016, although they probably began considerably earlier. (Perhaps Uber will respond to this article by determining, and telling the public, when the problems began.) In response to this article, I expect that Uber will fix these specific problems promptly. But given Uber’s massive operations — many thousands of new users per month — the aggregate harm is plausibly well into the millions of dollars.

Third, my experience calls into question whether Uber’s customer service staff are up to the task of investigating or resolving these problems. Writing in to customer service is fruitless; even with screenshots proving the discrepancy in the new user promotion, Uber was slow to promise a refund to match the marketing commitment. (It took five separate messages over eight weeks!) In fact, even after promising the refund in a message of March 16, 2016, that refund never actually occurred. Similarly, I promptly alerted Uber to the "next ride" credit not provided — but ten days later, I have received neither the promised credit nor any reply. Others have reported the shortfalls of Uber’s customer service staff including ineffective responses, a focus on response speed rather than correctness, and insufficient training. My experience suggests that these problems are genuine and ongoing. Users with the most complicated problems — Uber system flaws, discrepancies between records, billing errors — appear to be particularly unlikely to achieve resolution.

Finally, users lack meaningful recourse in responding to Uber’s overcharges. In each of the problems I found, Uber is overcharging a modest amount to each of many thousands of customers. Ordinarily, this would be a natural context for class action litigation, which would allow a single judge and a single set of lawyers to figure out what happened and how to set things right. But Uber’s Terms and Conditions purport to disallow users to sue Uber at all, instead requiring arbitration. Furthermore, Uber claims to disallow group arbitration, instead requiring that each consumer bring a separate claim. That’s inefficient and uneconomical. Uber’s arbitration clause thus provides a de facto free pass against litigation and legal remedies. Of course many companies use arbitration to similarly immunize themselves against consumer claims. But Uber’s controversial activities, including the overbilling described here among many other disputes, give consumers extra reason to seek judicial oversight.

Just last week, Uber formed a paid advisory board of ex-regulators, most with competition and consumer protection expertise. These experts should exercise independent judgment in looking into the full breadth of Uber’s problems. I doubt overbilling was previously on their agenda, but my experience suggests it should be. To investigate, they might review all customer service threads with five or more messages, plus look for all messages attaching screenshots or mentioning "overcharge" or "promised" or "contract." Tthey shouldn’t rely merely on Uber staff summaries of customer experience; with an advisory board of superstars, the group should bring independent judgment to assessing and improving the company’s approach.

Meanwhile, Uber’s response should include a full refund to each and every user who was overcharged. For example, when Uber promised a "free ride" to an Android user who in turn referred a friend, Uber should provide the friend with a refund to achieve exactly that — not just the $15 discount that may be what Uber intended but isn’t what the offer actually said. Since Uber may be disinclined to offer these refunds voluntarily, I’m alerting consumer protection and transportation regulators in appropriate jurisdictions to help push to get users what they were promised.