Reading ShopAtHomeSelect‘s marketing materials, their advertising software might seem to present compelling benefits. SAHS promises users rebates on products they’re already purchasing. And SAHS even offers reminder software to make sure forgetful users don’t miss out on the savings. What could be better than timely reminders of free money?

But the SAHS site doesn’t tell the whole story. My testing demonstrates that SAHS software is often installed without users wanting it, requesting it, or even accepting it. (Details.) When users receive an unwanted SAHS installation, SAHS still claims commissions on users’ purchases — but typical users will never see a penny of the proceeds. (Details.) Meanwhile, whether requested by users or not, SAHS’s commission-claiming practices seem to violate stated rules of affiliate networks. (Details.)

Despite these serious problems, SAHS boasts a superstar list of clients — the biggest merchants at all the major affiliate networks, including Dell, Buy.com, Expedia, Gap, and Apple. Why? Affiliate networks have little incentive to investigate SAHS’s practices or assure compliance with stated rules. (Details.) SAHS and affiliate networks profit, but users and merchants are left as victims. (Details.)

Update (October 14): Commission Junction has removed SAHS from its network, thereby ending SAHS’s relationships with all CJ merchants. No word on similar actions by LinkShare or Performics.

Wrongful Installations – No Consent, and Tricky So-Called “Consent”

ShopAtHomeSelect is widely known to become installed without meaningful consent — or, in many cases, without any consent at all. Most egregious are installations through security exploits, without any notice or consent. I continually test these installations in my lab, and I have repeatedly observed SAHS appearing unrequested — more than half a dozen such installs, occurring on distinct sites on distinct days. I posted one such video in May, and I retain the others on file.

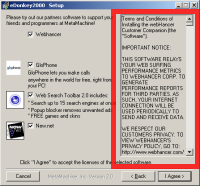

![]() SAHS’s improper installations extend to many of SAHS’s bundling partners. I have repeatedly seen (and often recorded) SAHS disclosed midway through lengthy license agreements; users often have to scroll through dozens of pages to learn of SAHS’s inclusion. Even worse, some programs that bundle SAHS nonetheless fail to mention SAHS’s inclusion. See e.g. 3D Flying Icons, which shows a 12-page 2,286-word license that makes no mention of SAHS, yet 3D installs SAHS anyway. (Screenshot at right.)

SAHS’s improper installations extend to many of SAHS’s bundling partners. I have repeatedly seen (and often recorded) SAHS disclosed midway through lengthy license agreements; users often have to scroll through dozens of pages to learn of SAHS’s inclusion. Even worse, some programs that bundle SAHS nonetheless fail to mention SAHS’s inclusion. See e.g. 3D Flying Icons, which shows a 12-page 2,286-word license that makes no mention of SAHS, yet 3D installs SAHS anyway. (Screenshot at right.)

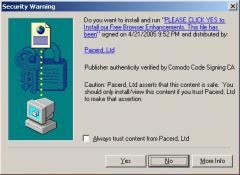

In other instances, ActiveX popups pressure users to accept multiple advertising programs in the guise of “browser enhancements” (or similar). In February 2005, I observed an ActiveX popup that labeled itself “website access” and “click yes to continue,” but immediately installed SAHS if users pressed yes once. More recently, I posted an analysis of the PacerD ActiveX. (Screenshot at left.) PacerD’s ActiveX popup links to a license agreement which discloses installation of eight advertising programs — but doesn’t mention SAHS, though Pacer in fact does install SAHS. So even when careful users take the time to examine Pacer’s 1,951-word license, in hopes of learning what they’re getting, there’s no way to learn that SAHS will be installed, not to mention grant or deny consent.

In other instances, ActiveX popups pressure users to accept multiple advertising programs in the guise of “browser enhancements” (or similar). In February 2005, I observed an ActiveX popup that labeled itself “website access” and “click yes to continue,” but immediately installed SAHS if users pressed yes once. More recently, I posted an analysis of the PacerD ActiveX. (Screenshot at left.) PacerD’s ActiveX popup links to a license agreement which discloses installation of eight advertising programs — but doesn’t mention SAHS, though Pacer in fact does install SAHS. So even when careful users take the time to examine Pacer’s 1,951-word license, in hopes of learning what they’re getting, there’s no way to learn that SAHS will be installed, not to mention grant or deny consent.

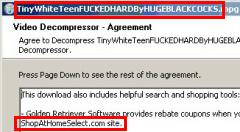

I’m not the only observer to notice SAHS installed improperly. Earlier this month, VitalSecurity.org reported SAHS installed via IM spam: Users receive an unsolicited instant message, and clicking the message’s link installs SAHS (among other programs) without any notice or consent. Last month, PC Pitstop (1, 2) and VitalSecurity.org reported SAHS bundled with porn videos distributed by BitTorrent — so a user seeking adult entertainment would unwittingly receive SAHS too. In my testing of these BitTorrent videos, SAHS was listed in a license agreement preceding the videos, but users had to scroll past four pages of other text to learn of SAHS’s inclusion, and even then SAHS’s mention was only a single sentence — without even a link to an external SAHS license agreement, and without any description of the privacy effects of installing SAHS software. (See screenshot at right.) Furthermore, these BitTorrent videos aren’t SAHS’s only tie to porn videos. In January, I analyzed ActiveX popups triggered by porn videos. These popups falsely claimed to be required to view the videos, but in fact they were mere ploys seeking to install SAHS and other advertising software.

I’m not the only observer to notice SAHS installed improperly. Earlier this month, VitalSecurity.org reported SAHS installed via IM spam: Users receive an unsolicited instant message, and clicking the message’s link installs SAHS (among other programs) without any notice or consent. Last month, PC Pitstop (1, 2) and VitalSecurity.org reported SAHS bundled with porn videos distributed by BitTorrent — so a user seeking adult entertainment would unwittingly receive SAHS too. In my testing of these BitTorrent videos, SAHS was listed in a license agreement preceding the videos, but users had to scroll past four pages of other text to learn of SAHS’s inclusion, and even then SAHS’s mention was only a single sentence — without even a link to an external SAHS license agreement, and without any description of the privacy effects of installing SAHS software. (See screenshot at right.) Furthermore, these BitTorrent videos aren’t SAHS’s only tie to porn videos. In January, I analyzed ActiveX popups triggered by porn videos. These popups falsely claimed to be required to view the videos, but in fact they were mere ploys seeking to install SAHS and other advertising software.

In short, a user receiving SAHS cannot reasonably be claimed to have wanted SAHS, nor to have granted informed consent. Perhaps some SAHS users run SAHS willingly and knowingly, but many clearly do not.

In contrast, affiliate networks’ rules set a high burden for installation disclosure and consent. LinkShare’s Shopping Technologies Addendum (PDF) requires that disclosure be “full and prominent,” a standard met neither by SAHS’s nonconsensual installations, nor by its installation when bundled with porn videos. Commission Junction’s Publisher Code of Conduct requires that disclosure be “clearly presented to and accepted by” users, and CJ specifically prohibits software that is “installed invisibly” (as in the nonconsensual installations detailed above).

SAHS may claim that these wrongful installations have stopped. But that’s just not credible. I’ve continued to see (and record) these installations as recently as the past few days.

SAHS may say these wrongful installations are the fault of its distributors. (SAHS offered that argument when PC Pitstop inquired as to SAHS bundling with porn videos.) But affiliate networks’ rules do not forgive wrongful installations merely because the installations were performed by others. To the contrary, affiliate networks set out high consent requirements which apply no matter who installs the software. Furthermore, with so many diverse wrongful installations over such an extended period, it’s clear that something is fundamentally wrong with SAHS’s installation methods; SAHS can’t escape responsibility by vague finger-pointing.

Update (September 9): Staff from SAHS have prepared a document (PDF) purporting to rebut my findings of nonconsensual and dubious installations of SAHS. In each instance, SAHS claims they weren’t really installed in the manner I describe, so they say I am “mistaken” as to my allegations. Let’s look at each of the types of installations I described, and review the evidence:

Tricky popups (PacerD specifically): I previously posted an analysis of PacerD’s installation, including a screenshot of new folders created by PacerD. SAHS correctly notes that there’s no new folder containing SAHS files. But the lack of a new Program Files folder doesn’t mean SAHS wasn’t installed; quite the contrary, SAHS was installed by PacerD. Furthermore, SAHS was installed into the c:Windows directory, where inexperienced users are unlikely to look for it, and where its files tend to become jumbled with other files. To document this installation, I have added two new screenshots to my SAHS write-up, showing newly-created SAHS files placed in my c:Windows directory. I also have on file a video, showing the installation of the PacerD ActiveX followed (without interruption in the video) by the creation of these files. I also have on file a packet log indicating the newly-installed copy of SAHS contacting SAHS servers. So my initial write-up was right and SAHS’s response is wrong: PacerD did indeed install SAHS — and it did so without mentioning SAHS in any EULA or other disclosure.

Large bundles with little or no disclosure (3D Flying Icons specifically): Here again, SAHS makes the same analytical error. My write-up reports lots of new folders (within c:Program Files) reflecting other programs becoming installed. SAHS didn’t add a folder to c:Program Files, so it didn’t come up in my Program Files screenshots. But SAHS absolutely was installed by 3D. In a video I made at the time (now also posted to my public site), I observed a SAHS installer created in c:Temp (1:44), and I saw SAHS program files in c:Windows at 2:43, in each instance bearing distinctive SAHS icons as well as typical SAHS filenames. So there can be no disputing that 3D installs SAHS.

Nonconsensual installations through security holes: The section above links to a particular single security exploit video, one of literally scores I have on file. My automated network log analysis, file-change, and registry-change analysis confirm that SAHS was installed in the course of that security exploit, and Ad-Aware logs say the same, but the video does not specifically show the installation. That’s not particularly surprising — SAHS installs can be silent, and I wasn’t specifically seeking to document SAHS installs when I made that video. But rather than worry about this single example from so many months back, let me take this opportunity to post a recent example, showing a nonconsensual SAHS installation I happened to receive just last month (August 2005). In this video, I view a page at highconvert.com (video at 0:05), receive a series of security exploits (0:20-0:30), browse my file system and diagnostic tools, and then get a popup indicating that SAHS has been installed (1:57) (screenshot). My packet log and change-logs also confirm the SAHS installation.

So where does this leave my claims of improper SAHS installations? Notwithstanding SAHS’s promises of legitimacy, there can be no doubt of SAHS becoming installed without consent. SAHS may not like to admit it, and SAHS produces intense rhetoric to deny it, but users with SAHS aren’t all “opt-in.” To the contrary, some SAHS users have SAHS just because they’re unlucky enough to get it foisted upon them. And contrary to SAHS’s claim that my findings are “incorrect,” I have ample proof of these nonconsensual SAHS installs.

Wrongful Operation – Forced Clicks

In addition to regulating installation methods, affiliate networks’ rules limit the ways in which affiliates may claim affiliate commissions. Commission Junction’s Publisher Code of Conduct prohibits claiming commissions on “non-end-user initiated events” — invoking affiliate links without an “affirmative end-user action.” LinkShare’s Shopping Technologies Addendum (PDF) lacks a corresponding prohibition of non-end-user initiated events, but LinkShare’s Affiliate Membership Agreement repeatedly calls for affirmative user actions as a necessary condition to earning commission. For example, LinkShare’s provision 1.1 says commissions are payable only for “users who activate the hyperlink” (emphasis added); the “users … activate” wording specifically contemplates a user taking an affirmative action, not merely a software program automatically opening a link. (Since LinkShare’s special Addendum lacks any provision to the contrary, these Agreement terms still apply.)

There are good reasons for these rules: Affiliate merchants often make substantial payments if an affiliate link is activated and a user makes a purchase. (For example, Dell could easily pay $10+ for a single purchase through a single link.) So software programs aren’t allowed to “click” on affiliate links automatically. Instead, users must actually show some interest in the links — protecting merchants from being asked to pay commissions when an affiliate did nothing to earn a fee.

Although applicable network rules require that clicks on affiliate links be affirmative and that such clicks actually be performed by users (not just by software), SAHS software opens affiliate links and claims commissions without users taking any specific action. See e.g. this SAHS-Dell video, showing a user requesting www.dell.com on a computer with SAHS installed. SAHS immediately redirects the user to its affiliate link to Dell (video at 0:06), and LinkShare affiliate cookies are created (0:08), all without a user affirmatively clicking on any SAHS affiliate link. See also a corresponding SAHS video for Buy.com, showing affiliate link being loaded (0:06) and cookies created (0:10), again without any user interaction.

So SAHS’s operation constitutes an apparent violation of applicable network rules — claiming affiliate commission without the required user click on an affiliate ad, seemingly contrary to network rules.

I began this piece with the claim that affiliate networks have allowed SAHS to remain in their networks, notwithstanding the violations set out above. Why?

One possibility is that the affiliate networks simply never noticed the violations. But that’s a suggestion I can’t accept. Consider the many articles above, each reporting wrongful installations. Much of this work received extensive media coverage, including discussions on industry sites of record. Furthermore, most of these findings can be verified easily using any ordinary PC. So affiliate networks can’t credibly claim ignorance of what was occurring.

More persuasive, in my view, is the theory that affiliate networks declined to punish SAHS because SAHS’s actions are profitable for affiliate networks. When an affiliate merchant pays a commission to an affiliate, that merchant must also pay a fee to the intermediary affiliate network. Commission Junction’s public pricing list reports that this fee is 30% — so for every $1 of commission paid to SAHS, CJ earns another $0.30. As a result, affiliate networks have clear financial incentives to retain even rogue affiliates. (Indeed, at the same time that adware has exploded to infect tens of millions of PCs, CJ and LinkShare are reporting unusually strong earnings. [1, 2])

I don’t want to overstate my worry of affiliate networks’ profit motivation. In recent months, affiliate networks have repeatedly kicked out long-time rule-breakers, even where the rule-breakers make money for the networks. (See e.g. LinkShare kicking out 180solutions, and CJ kicking out 180solutions, Direct Revenue and eXact Advertising.) But these actions generally only occur after an extended period of user and analyst outcry. (See e.g. my writing last summer about 180solutions’ effects on affiliate systems.) In contrast, to date, little attention has been focused on SAHS.

Update (October 14): Commission Junction has removed SAHS from its network, thereby ending SAHS’s relationships with all CJ merchants. No word on similar actions by LinkShare or Performics.

Merchants and Users as Victims

As shown in the example video linked above, SAHS claims affiliate commissions even when users specifically request merchants’ sites. Dell and Buy.com get no bona fide benefit from paying 1%-2% to SAHS, as shown in the videos above. SAHS might claim that it pays users rebates as a way to encourage their purchases from participating merchants. But when SAHS arrives on users’ PCs unrequested, and even without users’ acknowledgement or acceptance of its arrival, users are unlikely to be motivated to make purchases from SAHS-participating merchants. So it’s unclear what benefit SAHS can offer merchants under these circumstances.

Notwithstanding the problems with SAHS’s business, affiliate networks encourage merchants to make payments to SAHS by listing SAHS as an affiliate in good standing, inviting SAHS staff to conferences, and occasionally even giving awards to SAHS. Whether through these network actions or based on merchants’ own failure to diligently investigate, merchants bear the brunt of SAHS’s bad actions — paying out commissions SAHS has not properly earned under stated affiliate network rules.

Users also suffer from SAHS. As a result of the ill-gotten payments paid to SAHS by merchants, SAHS receives funds with which it can and does purchase additional installations from its software distribution partners (including the nonconsensual and tricky installations shown above). Payments from Dell (and other targeted merchants) ultimately help to fund the infection of more users — slowing down more users’ PCs, making more users’ PCs unreliable, and pouring fuel onto the spyware problem. To the extent that affected users respond by buying new PCs, Dell perhaps benefits indirectly — but I gather Dell does not aspire to fund such infections.

SAHS may claim that users benefit from its presence, even if its initial installation was improper. After all, SAHS claims affiliate commissions based on users’ purchases, and SAHS stands ready to refund a share of these commissions to the responsible users. But from the perspective of users who received SAHS without meaningful disclosures, SAHS’s offer is of dubious value. Where a program arrives unrequested, users’ fears of identity theft or fraud will (rightly!) discourage them from providing the personal information necessary to receive a payment (name, address, etc.). SAHS may be offering users legitimate actual payments — but when SAHS’s installation was nonconsensual in the first place, users have no easy way to distinguish SAHS’s offer from a phishing attempt or other scam. Without payment details, SAHS will simply retain users’ funds — giving users no benefit for the unrequested intrusion on their PCs, but giving SAHS extra profits.

This is an unfortunate situation — but it’s not hopeless. Dell, Buy.com, and other affected merchants need not continue to help fund this mess. LinkShare and Commission Junction need not continue to pass money to SAHS from unwitting merchants, nor need they continue taking 30% cuts for themselves. Stay tuned.

Update (September 13): News coverage discusses the problem of SAHS retaining commissions for users who never requested SAHS and never even registered for rebates. CJ claims that they have not confirmed “SAHS performing redirects on unregistered users,” but admits that this would be a “major violation.” I have provided CJ with screenshot and video proof, showing SAHS doing exactly that.

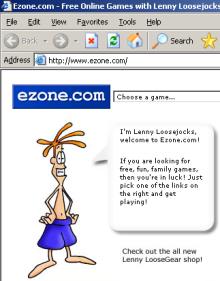

Can we say that a user “consents” to an installation if the installation occurred after a user was presented with a misleading advertisement that looked like a Windows dialog box? If that advertisement was embedded within a site substantially catering to children? If that advertisement offered a feature known to be duplicative with software the user already has? If “authorizing” the installation required only that the user click on an ad, then click “Yes” once? If the program’s license agreement was shown to the user only after the user pressed “Yes”? These are the facts of recent installations of Claria software from ads at games site Ezone.com.

Can we say that a user “consents” to an installation if the installation occurred after a user was presented with a misleading advertisement that looked like a Windows dialog box? If that advertisement was embedded within a site substantially catering to children? If that advertisement offered a feature known to be duplicative with software the user already has? If “authorizing” the installation required only that the user click on an ad, then click “Yes” once? If the program’s license agreement was shown to the user only after the user pressed “Yes”? These are the facts of recent installations of Claria software from ads at games site Ezone.com.