VeriSign hates spyware — or so suggests CEO Stratton Sclavos in a recent interview. Even his daughter’s computer got infected with scores of unwanted programs, Sclavos explains, but he says VeriSign is helping to solve this problem. The ironic reality is Sclavos’ daughter’s computer was most likely infected via popups that appeared trustworthy only thanks to certificates issued by VeriSign. If Sclavos is serious about cracking down on spyware, VeriSign can end many deceptive installation practices just by enforcing its existing rules.

Drive-By Installs, Digital Signatures, and VeriSign’s Role

In 2002, Gator introduced ActiveX “drive-by downloads” — popups that attempt to install unwanted software onto a user’s PC as a user browses an unrelated web site. Today, Windows XP Service Pack 2 offers some protection by blocking many drive-by installation attempts. But for users with earlier versions of Windows, who can’t or don’t want to upgrade, these popups remain a major source of unwanted software. (And even SP2 doesn’t stop all drive-bys. For example, SP2 users with Media Player version 9, not the new v10, are still at risk.)

Even though Microsoft can’t (or won’t) fully fix this problem, VeriSign can. Before an ActiveX popup can install software onto a user’s computer, the installer’s “CAB file” must be validated by its digital signature. If the signature is valid, the user’s web browser shows the ActiveX popup, inviting a user to install the specified software. But if the signature is invalid, missing, or revoked, the user doesn’t get the popup and doesn’t risk software installation.

Microsoft has accredited a number of providers to offer these digital certificates. But in practice, almost all certificates are issued by VeriSign, also owner of Thawte, previously the second-largest player in this space. (See a findlaw.com antitrust discussion message noting that, as of February 2000, the two providers jointly held 95% of the digital certificate market.)

Through existing software systems, already built into Internet Explorer and already implemented by VeriSign servers, VeriSign has the ability to revoke any certificate it has previously issued, disabling ActiveX installations that use that certificate. See VeriSign’s Certificate Revocation List server (crl.verisign.com) and Microsoft Certificates documentation of the revocation system.

I suggest that VeriSign can and should use its existing certificate revocation system to disable those certificates issued or used in violation of applicable VeriSign rules.

Examples of the Problem, and A Specific Proposal

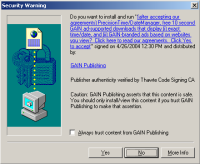

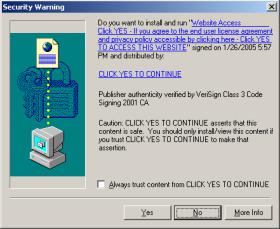

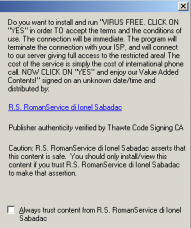

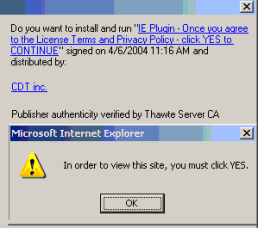

Consider the three misleading ActiveX installers shown below. The first gives an invalid company name (“click yes to continue”). The second gives a misleading/missing product name (“virus free”). The third was shown repeatedly, between popups that falsely claimed “In order to view this site, you must click YES.” Click on each inset image to see a full-size, uncropped version.

Each of these misleading installations is contrary to VeriSign contract, contrary to VeriSign’s duty to its users, and contrary to VeriSign’s many promises of trustworthiness. In the first installer, VeriSign affirmatively certified the “click yes to continue” company name — although it seems that there exists no company by that name, and although that company name is facially misleading as to the purpose of the installation prompt. In the second and third examples, VeriSign certified companies that subsequently used VeriSign’s certification as a necessary step in deceiving users as to the function of and (alleged) need for their programs.

Given VeriSign’s claims (such as its old motto, “the value of trust”), VeriSign should want to put an end to these practices. When VeriSign certificates are issued wrongfully (as in the first example) or are used deceptively (as in the second and third), VeriSign should take action to protect users from being tricked. In particular, when an application offers a facially invalid and misleading company name, VeriSign should refuse to issue the requested certificate. When an applicant violates basic standards of truth-telling and fair dealing, VeriSign should revoke any certificates previously issued to that applicant.

Why VeriSign Should Get Involved

VeriSign’s intervention would be entirely consistent with its existing contracts with certificate recipients. For example, section 11.2 (certificate buyer’s representations) requires a certificate buyer to represent that it has provided accurate information — including an accurate company name. The purported company name “click yes to continue” surely violates the accuracy requirement, meaning the certificate supporting the first popup above is prohibited under VeriSign rules.

Furthermore, VeriSign’s section 4 (“Use Restrictions”) prohibits using VeriSign certificates “to distribute malicious or harmful content of any kind … that would … have the effect of inconveniencing the recipient.” The dialers, toolbars, tracking systems, and advertising systems provided by the second and third popups are indisputably inconvenient for users. I claim the resulting software is also “malicious” and/or “harmful” in that it tracks users’ personal information, slows users’ computers, shows extra ads, and/or accrues long-distance or 900 number access costs. So these installation prompts also violate applicable VeriSign rules.

VeriSign’s contracts grant VeriSign the power to take action. Section 5 explains that “VeriSign in its sole discretion retains the right to revoke [certificates] for [certificate buyers’] failure to perform [their contractual] obligations.” So VeriSign has ample contractual basis to revoke the misleading certificates.

Contractual provisions notwithstanding, I anticipate certain objections to my proposal. The obvious concerns, and my responses —

- It’s too hard and too costly for VeriSign to find the wrongdoers. But VeriSign is a huge company, and a market leader in online security, infrastructure, and trust. Also, confirming the legitimacy of certificate recipients is exactly what VeriSign is supposed to be doing in the course of its certificate issuance. VeriSign charges $200 to $600 per certificate issued. At present it’s unclear what verification VeriSign performs — what work VeriSign does to earn $200+ for each certificate issued. The procedures I’m proposing might require a few new employees and some ongoing effort. But for a company precisely engaged in the business of certifying others’ practices, this testing is appropriate. Even if enforcement is costly, VeriSign stands to lose much more if it dilutes its brand and “trust” promise by failing to stop deceptive installations occurring under the guise of VeriSign certificates.

- There are some difficult border cases. I agree that not all ActiveX installers are as outrageous as those shown above. For example, Claria’s installers lack the most outrageous of the deceptive practices above — they give Claria’s true company name, and they don’t explicitly claim that installation is required. Yet Claria’s installers still have major deficiencies. For example, Claria’s installers fail to admit that Claria software will not just “monitor” user information but also collect and store such data (in what is reportedly the seventh largest database in world), and Claria’s software repeatedly tries to install even if users decline when initially asked. What should VeriSign do with a case like Claria? I consider Claria’s installation practices deceptive and unethical, but I’m not sure it’s VeriSign’s role to make Claria stop. However, the existence of some hard decisions doesn’t mean VeriSign shouldn’t at least address the easy cases.

- XP SP2 already solved the ActiveX problem, so this is irrelevant. I disagree. Tens of millions of users still run old versions of Windows. Some users can’t afford the cost of an upgrade (new software plus, for many users, faster hardware). Others cannot upgrade due to corporate policies or compatibility concerns. Then there are problems for which even SP2 doesn’t offer full protection: WindowsMedia files can still open ActiveX popups and installer decoys that try to trick users into authorizing installations.

VeriSign’s intervention would make a big difference. VeriSign could stop many misleading software installation practices, including those shown above, and block what remains a top method of sneaking onto users’ PCs. Unlike spammers who switch from one server to another, spyware distributors can’t just apply for scores of new digital certificates, because each application entails out-of-pocket costs.

Plans for an Enforcement Procedure

Enforcement of invalid company names would be particularly easy since VeriSign already has on hand the purported company names of all its certificate recipients. Entries like “click yes to continue” stick out as facially invalid. Simply reading through the list of purported company names should identify wrongdoers like “click yes to continue” — applicants whose certificates should be investigated or disabled.

It’s admittedly somewhat harder for VeriSign to stop certain other deceptive practices that use VeriSign-issued certificates. While VeriSign knows the company names associated with all its certificates, VeriSign’s systems apparently don’t currently track the purported product names signed using VeriSign certificates. Furthermore, VeriSign receives no special warning when a certificate recipient uses tricky JavaScript to repeatedly display an installation attempt or to intersperse displays with “you must click yes” (or similar) popups.

But VeriSign could at least establish a formal complaint and investigation procedure to accept allegations of violations of applicable contracts. Other VeriSign departments offer web forms by which consumers can report abuse. (See e.g. the SSL Seal Report Misuse form.) Yet VeriSign’s Code Signing page lacks any such function, as if wrongdoing were somehow impossible here. Meanwhile, those with complaints have nowhere to send them. Indeed, I’ve reviewed complaints from Richard Smith and others, flagging both wrongly-issued certificates and the need for a complaint procedure, and raising these issues as early as January 2000.

Of course, beyond receiving and investigating consumer complaints, VeriSign could also run tests on its own — affirmatively seeking out bad actors who use VeriSign certificates contrary to VeriSign’s rules.

Update: Reponses from VeriSign and eWeek’s Larry Seltzer

After I published the article above, I received two responses from VeriSign staff. Phillip Hallam-Baker, VeriSign’s Chief Scientist, wrote to me on February 4 (the day after I posted my article) to say that “Click yes to continue was disabled yesterday.” Staff from VeriSign’s “Certificate Practices” department subsequently wrote to discuss current practices and to ask what more VeriSign could do here. They all seemed pretty reasonable — willing to admit that VeriSign’s practices could be better, and interested in reviewing my findings.

In contrast, I was struck by the response from eWeek‘s Larry Seltzer. Larry apparently spoke with VeriSign PR staff at some length, and he liberally quotes VeriSign staff defending having issued a certificate to “Click Yes to Continue.” Saying that I “may have jumped to a conclusion,” Larry seems to credit VeriSign’s claim that the bogus certificate problem was “basically all over” as soon as (or even before) I posted my article. I emphatically disagree. There are hundreds (thousands?) of certificates that continue to break VeriSign rules — for example, claiming to be security updates when they are not, or claiming “you must press yes” when they’re not actually required. (See also VeriSign-issued certs supporting misleading popups shown at Google Blogspot.) VeriSign may prefer not to enforce its own rules, prohibiting “distribut[ing] malicious or harmful content of any kind … that would … have the effect of inconveniencing the recipient.” And Seltzer may think VeriSign shouldn’t have such rules. But the rules do exist — VeriSign itself wrote them! — and the rule violations are clear and ongoing. That VeriSign revoked a few egregious certificates after I posted my article doesn’t mean VeriSign’s practices are up to par otherwise. What about all the other certs that break the rules?

Finally, Seltzer claims that VeriSign told me Click Yes to Continue is a valid company name. Nope. First, the premise is wrong; that’s just not a valid company name, because it’s facially misleading. Second, VeriSign never told me any such thing: I have carefully reviewed my email records, and no VeriSign staff person made any such statement. (To the contrary, see the Hallam-Baker quote above, admitting that Click Yes was in violation and was disabled.) Maybe VeriSign should spend more time investigating its rule violations, and less time trying to smear those who criticize its poor enforcement record.

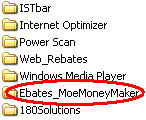

Screen-shot of my Program Files folder, showing some of the programs installed on my test computer.

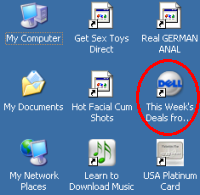

Screen-shot of my Program Files folder, showing some of the programs installed on my test computer. Screen-shot of the icons added to my test computer’s desktop. Note a new link to Dell — an affiliate link such that Dell pays commissions when users make purchases after clicking through this link.

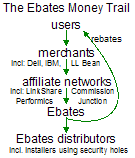

Screen-shot of the icons added to my test computer’s desktop. Note a new link to Dell — an affiliate link such that Dell pays commissions when users make purchases after clicking through this link. Partial screen-shot taken from video of Ebates installation through a security hole, without any notice or consent.

Partial screen-shot taken from video of Ebates installation through a security hole, without any notice or consent. For users who share my continued interest in

For users who share my continued interest in