At first glance, conversion-contingent advertising (cost-per-action / CPA, affiliate marketing) seems a robust way to prevent online advertising fraud. By paying partners only when a sale actually occurs, advertisers often expect to substantially eliminate fraud. After all, if commissions are only due when a user makes a purchase, what can go wrong? Unfortunately, this view is overly simplistic and, on balance, overly optimistic.

I’ve previously written at length about spyware and adware programs that watch a user’s web browsing in order to claim commission on sales that would have happened anyway. See last week’s examples of six different affiliates cheating VistaPrint through exactly this technique.

But CPA fraud does not require the use of spyware or adware on a user’s computer. To the contrary, I’ve seen plenty of CPA fraud that is entirely web based. Below I present three examples representative of this ongoing problem.

The Basic CPA Relationship

CPA advertising generally oblige an advertiser to pay a commission if three events occur:

- A user browses an affiliate’s web site;

- A user clicks a specially-coded link to a participant CPA merchant; and

- A user makes a purchase from that merchant.

The purchase in step 3 may occur immediately, i.e. within a single browsing session. But even if the purchase occurs shortly thereafter, e.g. a day later or even a few weeks later, a merchant will typically credit this purchase to the corresponding affiliate — on the view that the affiliate at least introduced the user to the merchant. This extended credit period is typically known as the “return-days period.”

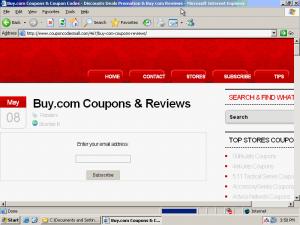

Example 1: Couponcodesmall Forces Clicks to Drop Buy.com Cookies

The Couponcodesmall Site – Cookie-Stuffing Invisibly

The Couponcodesmall Site – Cookie-Stuffing Invisibly

Some affiliates seek to bypass the user-click requirement (event 2 above) by simulating a click on an affiliate link using JavaScript. When the user merely visits the affiliate’s site, the affiliate forces the user’s browser to load an affiliate link — thereby placing affiliate cookies on the user’s PC, and claiming an affiliate commission if the user subsequently makes a purchase from the corresponding merchant.

In 2004, I presented 36 such examples in Cookie-Stuffing Targeting Major Affiliate Merchants, But the problem is ongoing.

In testing this month, I requested a page from Couponcodesmall, a top organic result for Google searches for “buy.com coupon” (without quotes). Couponcodesmall sent more than 65KB of HTML, followed by the following IFRAME:

<iframe SRC=”http://affiliate.buy.com/gateway.aspx?adid=17662&aid=10389736&pid=2705091&sid=&sURL=http%3A//www.buy.com/” WIDTH=5 HEIGHT=5 frameborder=”0″ scrolling=”no”></iframe>

I preserved a full packet log that shows this IFRAME in context. (Edit-Find on “IFRAME” to skip to the key section.) I also preserved a screen-capture video showing the cookies created after I requested this page — confirming the IFRAME‘s effect. As the HTML instructs, the IFRAME yields no visible on-screen indication — for the IFRAME‘s 5 pixel by 5 pixel size (blue highlighting) leaves too little space for the Buy.com site to be recognized.

Buy.com’s agreement with affiliates requires that affiliates comply with Commission Junction’s Publisher Service Agreement (PSA), and PSA rule 3.a grants credit only when a user “clicks through [a] Link[] to [an] Advertiser.” This affiliate’s IFRAME-delivered forced clicks exactly violate that requirement. If a user merely views this affiliate’s page, without clicking an ad or taking any other action, then this affiliate will receive a 3% to 5% commission on any purchase the user makes from Buy.com within the next 14 days, even though the user never clicked an affiliate link as required under the PSA.

I notified the affiliate program manager for Buy.com, and I gather that Buy.com is taking appropriate action.

Similar infractions remain easy to uncover. My automated testing systems typically uncover a dozen or more violations in a day of searching. I’ve also seen all manner of advances over the popups, popunders, and IMG tags I observed in 2004. For example, I now often observe cookie-stuffing using EMBED tags, OBJECT tags, HTML entity encoding, and doubly-encoded JavaScript.

Example 2: Allebrands Banner Ads Invisibly Load Affiliate Links

Other affiliates load affiliate links and drop affiliate cookies as users merely view a banner ad. From a rogue affiliate’s perspective, this attack is more effective than the attack in Example 1, for the affiliate need not get the user to visit the affiliate’s site. Instead, merely by viewing a banner ad on a third party web page, the affiliate can drop its cookies and obtain a commission on purchases users make from the targeted merchants within the return-days period.

That is, the affiliate bypasses both the user click requirement (event 2 above) as well as the browsing requirement (event 1 above). Removing this additional requirement lets the affiliate claim commission on more users’ browsing that much more easily.

To targeted merchants, this attack is importantly worse than the attack in Example 1. In particular, through this kind of attack, a merchant receives no promotional benefit whatsoever. Under this attack, merchants pay out commission only on sales that would have happened anyway — so every commission paid is entirely wasted.

I recently observed such an attack via a banner ad running on the Yahoo RightMedia Exchange. Merely by viewing an ad from Allebrands, a user’s computer was instructed to load three affiliate links, each in a 0x0 IFRAME. Below is the relevant portion of the HTML code (formatted for brevity and clarity):

GET /iframe3? …

…

Host: ad.yieldmanager.com

…

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Mon, 29 Sep 2008 05:36:02 GMT

…

<html><body style=”margin-left: 0%; margin-right: 0%; margin-top: 0%; margin-bottom: 0%”><script type=”text/javascript”>if (window.rm_crex_data) {rm_crex_data.push(1184615);}</script>

<iframe src=”http://allebrands.com/allebrands.jpg” width=”468″

height=”60″ scrolling=”no” border=”0″ marginwidth=”0″

style=”border:none;” frameborder=”0″></iframe></body></html>

GET /allebrands.jpg HTTP/1.1

…

Host: allebrands.com

…

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

…

<a href=’http://allebrands.com’ target=’new’><img src=’images/allebrands.JPG‘ border=0></a>

<iframe src =’http://click.linksynergy.com/fs-bin/click?id=Ov83T/v4Fsg&offerid=144797.10000067&type=3&subid=0′ width =’0’height = ‘0’ boder=’0′>

<iframe src =’http://www.microsoftaffiliates.net/t.aspx?kbid=9066&p=http%3a%2f%2fcontent.microsoftaffiliates.net%2fWLToolbar.aspx%2f&m=27&cid=8′ width =’0’height = ‘0’ boder=’0′>

<iframe src =’http://send.onenetworkdirect.net/z/41/CD98773′ width =’0’height = ‘0’ boder=’0′>

The three IFRAMEs (green highlighting) load three separate affiliate links in three separate windows. Because these windows are each set to be 0 pixels wide and 0 pixels tall (blue highlighting), they are all invisible.

I preserved a full packet log of the entire HTTP sequence — showing traffic flowing from the underlying Smashits web site to Right Media to Allebrands to the target affiliate programs. (Edit-Find on “allebrands” to skip to Allebrands’ code.) I also notified the targeted merchants — McAfee, Microsoft, and Symantec. They’re taking appropriate action.

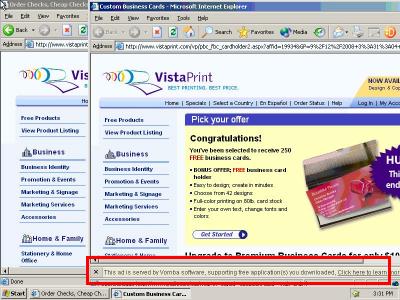

Allebrands’ Decoy Ad

Allebrands’ Decoy Ad

Notice Allebrands’ tricky use of the misleadingly-named /allebrands.jpg URL (yellow highlighting). In particular, Allebrands instructed Right Media to send traffic to http://allebrands.com/allebrands.jpg — a .JPG extension, so seemingly an ordinary JPEG compressed image. But despite the URL’s extension, the URL actually provided ordinary HTML — creating the A HREF, IMG, and IFRAME‘s set out above. Meanwhile, if a user happened to look at this ad, the user would see only the http://allebrands.com/images/allebrands.JPG image specified by the IMG tag (pink highlighting; image shown at right). Because the IFRAMEs are invisible (blue highlighting), the IFRAMEs yield no on-screen display whatsoever.

In my testing, Allebrands distributed its rogue banner ad via a variety of web sites. One that particularly caught my eye was Smashits, a spyware-delivered banner farm which buys widespread pop-up traffic and shows voluminous ads. Beyond Smashits’ dubious traffic origins, Smashits is also notable for its placement of ads in invisible windows: Via the two-row FRAMESET presented below, Smashits creates a 0-pixel-tall “part1” frame of /audio/empty.html, which in turn ultimately displays the Allebrands ad at issue.

<FRAMESET ROWS=”0,*” FRAMEBORDER=0 FRAMEPADDING=0 FRAMESPACING=0 BORDER=0>

<FRAME name=part1 SRC=”http://ww.smashits.com/audio/empty.html” NORESIZE MARGINWIDTH=0 MARGINHEIGHT=0 SCROLLING=”no”>

<FRAME name=part1a SRC=”http://ww.smashits.com/spindex_02.html” NORESIZE MARGINWIDTH=0 MARGINHEIGHT=0 SCROLLING=”yes”>

</FRAMESET>

Reviewing the packet log in the context of my prior observations of Smashits’ spyware-originating traffic, the full sequence of relationships proceeds as follows: A variety of spyware sends traffic to Smashits (often via the MyGeek / AdOn Network / Mynaagencies run-of-network ad loader), and some users may affirmatively request the Smashits site. Smashits creates a 0-pixel-tall FRAME row in which to load ads off-screen. In that frame Smashits sends traffic to Traffic Marketplace, which redirects the traffic to Theadhost, which redirects it to RightMedia Exchange, which selects an ad from Allebrands, which stuffs cookies to claim commission from the three target affiliate programs.

Who is Allebrands? Allebrands’ web site offers no contact information, and Allebrands’ Whois is equally uninformative. But Allebrands’ DNS servers reside within creativeinnovationgroup.com, and Creativeinnovationgroup’s Whois references a Simon Brown at 700 Settlement Street in Cedar Park, Texas. Google Maps confirms that this is a bona fide address — seemingly a residential unit in a development.

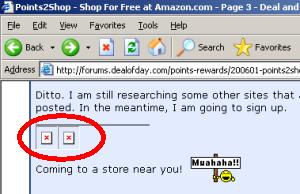

Example 3: Avxf Stuffing Amazon and Hostgator Cookies through Signature IMG Tags in DealOfDay Forum

In Example 1, Couponcodesmall managed to lure a user to its own web site — in part through successful search engine optimization. In Example 2, Allebrands bought traffic from Right Media. In this Example 3, affiliate rogue Avxf manages to stuff cookies using others’ traffic — without paying for that traffic.

To get traffic, Avxf places images in the footer of a message it posts to a DealOfDay.com forum discussion. The associated HTML:

Originally Posted by <strong>somerset1106</strong> …

Ditto. I am still researching some other sites that are similar. If I find out any information I will keep ya posted. …

<img src=”http://www.avxf.com/img16.jpg” border=”0″ alt=”” /><img src=”http://www.avxf.com/img17.jpg” border=”0″ alt=”” />

Avxf’s footer specified two .JPG URLs, /img16.jpg and /img17.jpg — seemingly image files based on their use of the standard .JPG file extension. But in fact these URLs redirect to affiliate programs for HostGator and Amazon:

GET /img16.jpg HTTP/1.1

…

Host: www.avxf.com

HTTP/1.1 302 Found

…

Location: http://secure.hostgator.com/cgi-bin/affiliates/clickthru.cgi?id=dsplcmnt01

…

GET /img17.jpg HTTP/1.1

…

Host: www.avxf.com

HTTP/1.1 302 Found

…

Location: http://www.amazon.com/?Fencoding=UTF8&tag=qufrho-20

Avxf Cookie-Stuffing:

Avxf Cookie-Stuffing:

The Resulting On-Screen Display

The resulting two pages then go on to drop affiliate cookies as usual. Thus, if a user makes a purchase at Amazon or Hostgator within their associated return-days periods, then Avxf gets paid a commission. The only on-screen indication of cookies being dropped is the two “broken image” icons shown at right — indications that something is missing, but in no way sufficient to inform a typical user (or even many advertising professionals) of what is occurring. Nonetheless, if a targeted user makes a purchase from Amazon within 24 hours of receiving Avxf’s forced click, or if a targeted user signs up with Hostgator within 30 days, then Avxf receives a commission.

I preserved a full packet log of the underlying HTML and redirects, showing Avxf’s images and redirects in context. (Edit-Find on “avxf” to skip to the code at issue.) I also preserved a screen-capture video confirming the destinations of the broken images.

Avxf’s practices violate applicable policies at Amazon and Hostgator. Amazon’s Associates program allows credit only if a customer “click[s] through” a special link (agreement 4¶1), whereas no click occurs in the example shown above. Furthermore, Amazon specifically prohibits atempts to “caus[e] any page of the Amazon Site to open in a customer’s browser other than as a result of hte customer clicking on a Special Link on [an affiliate’s] site” (agreement 4¶4). Similarly, the HostGator Affiliate Agreement prohibits the similar practice of forcing clicks through IFRAMEs (except “on pages or sites in which the other content represented on the site is related to HostGator” — an exception unavailable here, since the DealOfDay site is entirely unrelated to HostGator).

Who is Avxf? The Avxf web site offers adult content, but no mailing address on its Contact Us page. However, the site’s Whois offers a name and address: Kyle Hahn of Muncie, Indiana. Google Maps confirms the existence of the specified address, 480 W Skyway Drive.

Consequences – Winners and Losers

I see five basic consequences of these commission schemes:

- Fraudsters win from the bogus commission they receive, despite failing to provide merchants with a bona fide marketing benefit.

- Merchants pay extra commissions without getting anything in return. In particular, merchants pay commission on sales they would have made anyway. Moreover, merchants overestimate the effectiveness of their CPA marketing programs: Merchants mistakenly conclude that their CPA programs yielded sales that in fact would have happened anyway.

- Legitimate affiliates lose commissions that are seized by fraudsters. Whenever an ordinary affiliate was about to receive a commission, but one of these fraudsters jumps in to claim the commission instead, the first affiliate loses a commission it had fairly earned.

- Advertising intermediaries profit from the additional commissionable sales that purportedly occur. Affiliate networks typically charge merchants in proportion to the number (or dollar value) of commissionable sales. So every time a rogue affiliate claims commission improperly, the merchant must pay additional fees to the affiliate network.

- Affiliate marketing staff typically benefit, directly or indirectly, from growth in the reported size of their affiliate programs. For example, an affiliate manager might earn a bonus for rapid quarter-over-quarter growth in affiliate program size.

In principle, merchants’ losses to fraud should encourage merchants to prevent such scams. But in practice, many merchants fall victim to these attacks. Why?

For one, enforcement requires fact-intensive technical investigation — examining HTML code and packet logs to uncover infractions. The required skills have little overlap with the relationship-building and communication that otherwise drive affiliate marketing.

For some merchants and networks, mixed incentives further hinder efforts to prevent these fraudulent practices. In the short run, affiliate networks and merchants’ in-house affiliate marketing staff stand to lose from rigorous enforcement — reducing their commissionable base, reducing the size of their marketing programs, and distracting their attention from activities that more directly increase their respective short-run compensation. Thus, in the short run, both groups may perceive that they can increase their profits by deemphasizing fraud prevention.

Of course, in the long run, affiliate networks have reputations to protect. Similarly, affiliate marketing staff must consider their duties to their employers; in the long run, employers may learn about these scams and think unfavorably of marketing staff who failed to take effective action to uncover improper practices.

Large Merchants at Heightened Risk

For many cookie-stuffing attacks, large merchants are at highest risk. For example, Avxf is essentially betting that the users who read DealOfDay will subsequently go on to make purchases from Amazon. As to Amazon, that’s a safe bet, for many users buy from Amazon with remarkable regularity. But if Avxf were to target a lesser-known merchant, it would face tougher odds and lower earnings.

Thus, these random cookie-stuffing attacks (as in Examples 2 and 3) tend to target large merchants. In contrast, SEO-based attacks, as in Example 1, can prey on CPA merchants of any size.

Prevention and Response

For merchants and networks seeking to uncover and prevent these practices, I see three clear ways forward:

- Analyze statistics already on hand . Look for unusually high click-through rates, unusually low conversion rates, blank or unexpected HTTP Referer headers, unusual HTTP User-Agent headers, long delays between clicks and sales, and other errata. But beware of affilates who manage to manipulate these statistics.

- Provide a report / complaint page. It’s surprisingly difficult for independent affiliates, users and researchers to report fraud to many online marketers. But such reports can be extremely useful — particularly when gathered by those with a special interest in catching these scams. There’s ample evidence that affiliates enjoy reporting scams: In the ParasiteWare forum at ABestWeb, affiliates and others analyze and reveal improper marketing practices; some merchants pay bounties to anyone reporting fraud by their affiliates (1, 2).

- Conduct hands-on testing. Browse the web looking for such scams. Run a network monitor to detect any unexpected “click” events. Or, design appropriate software to conduct such tests automatically.

Separately, merchants and networks can sensibly deter violations through tough penalties. At present, affiliates face little downside to attempting to defraud most merchants. In Deterring Online Advertising Fraud Through Optimal Payment in Arrears, I suggest a different approach — paying affiliates more slowly so that they face greater losses if they are found to be cheating. Meanwhile, some merchants have resorted to suing fraudulent affiliates. See eBay v. Digital Point Solutions (accusing affiliates of cookie stuffing through invisible code claiming unearned commissions — like the examples above) and Lands’ End v. Remy (accusing affiliates of typosquatting on Lands’ End trademarks and redirecting to Lands’ End’s LinkShare affiliate links).

More generally, merchants ought not assume infallibilityof their online marketing schemes. Certainly CPA marketing programs avoid some of the more obvious problems of pay-per-click marketing (e.g. click fraud), but CPA campaigns remain vulnerable to other kinds of abuse. Shrewd merchants should anticipate what can go wrong, and design and audit accordingly.