Disclosure: I serve as a consultant to various companies that compete with Google. That work is ongoing and covers varied subjects, most commonly advertising fraud. I write on my own—not at the suggestion or request of any client, without approval or payment from any client.

Google claims that its Android mobile operating system is “open” and “open source”—hence a benefit to competition. Little-known contract restrictions reveal otherwise: In order to obtain key mobile apps, including Google’s own Search, Maps, and YouTube, manufacturers must agree to install all the apps Google specifies, with the prominence Google requires, including setting these apps as default where Google instructs. It’s a classic tie and an instance of full line forcing: If a phone manufacturer wants any of the apps Google offers, it must take the others also.

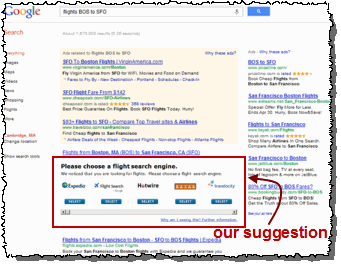

In this piece, I present relevant provisions from key documents not previously available for public examination. I then consider the effects on consumers, competitors, and competition, and I compare these revelations to what was previously known about Google’s mobile rules. I conclude by connecting Google’s mobile practices to Google’s use of tying more broadly

The Mobile Application Distribution Agreement

To distribute Google’s mobile applications—Google Search, Maps, YouTube, Calendar, Gmail, Talk, the Play app store, and more—a phone manufacturer needs a license from Google, called a Mobile Application Distribution Agreement (MADA). Key provisions of the MADA:

“Devices may only be distributed if all Google Applications [listed elsewhere in the agreement] … are pre-installed on the Device.” See MADA section 2.1.

The phone manufacturer must “preload all Google Applications approved in the applicable Territory … on each device.” See MADA section 3.4(1).

The phone manufacturer must place “Google’s Search and the Android Market Client icon [Google Play] … at least on the panel immediately adjacent to the Default Home Screen,” with “all other Google Applications … no more than one level below the Phone Top.” See MADA Section 3.4(2)-(3).

The phone manufacturer must set “Google Search … as the default search provider for all Web search access points.” See MADA Section 3.4(4).

Google’s Network Location Provider service must be preloaded and the default. See MADA Section 3.8(c).

These provisions are confidential and are not ordinarily available to the public. MADA provision 6.1 prohibits a phone manufacturer from sharing any Confidential Information (as defined), and Google labels the MADA documents as “Confidential” which makes the MADA subject to this restriction.

I know, cite, and quote these provisions—and I am able to share them with the public—because two MADA documents became available during recent litigation: In Oracle America v. Google, the HTC MADA and Samsung MADA were admitted as Trial Exhibit 286 and 2775, respectively. Though both documents indicate in their footers that they are “highly confidential – attorney’s eyes only,” both documents were admitted in open court (the clerk’s minutes indicate no admission under seal), and court staff confirm that both documents are available in the case records in the court clerk’s office. (However, the documents are not available for direct download in PACER. Instead, PACER docket number 1205 references “five boxes of trial exhibits placed on overflow shelf.”)

Effects on Consumers, Competitors, and Competition

These MADA provisions serve both to help Google expand into areas where competition could otherwise occur, and to prevent competitors from gaining traction.

Consider the impact on a phone manufacturer that seeks to substitute an offering that competes with a Google app. For example, a phone manufacturer might conclude that some non-Google service is preferable to one of the listed Google Applications—perhaps faster, easier to use, or more protective of user privacy. Alternatively, a phone manufacturer might conclude that its users care more about a lower price than about preinstalled Google apps. Such a manufacturer might be willing to install an app from some other search engine, location provider, or other developer in exchange for a payment, which would be partially shared with consumers via a lower selling price for the phone. Google’s MADA restrictions disallow any such configuration if the phone is to include any of the listed Google apps.

Tying its apps together helps Google whenever a phone manufacturer sees no substitute to even one of Google’s apps. Manufacturers may perceive that Bing Search, Duckduckgo, Yahoo Search, and others are reasonable substitutes to Google Search. Manufacturers may perceive that Bing Maps, Mapquest, Yahoo Maps, and others are reasonable substitutes to Google Maps. But it is not clear what other app store a manufacturer could preinstall onto a smartphone in order to offer a comprehensive set of apps. Furthermore, a manufacturer would struggle to offer a phone without a preinstalled YouTube app: Without the short-format entertainment videos that are YouTube’s specialty, a phone would be unattractive to many consumers—undermining carriers’ efforts to sell data plans, and putting the phone at heightened risk of commercial failure. Needing Google Play and YouTube, a manufacturer must then accept Google Search, Maps, Network Location Provider, and more—even if the manufacturer prefers a competitor’s offering or prefers a payment for installing some alternative.

In principle, the MADA allows a phone manufacturer to install certain third-party applications in addition to the listed Google Applications. For example, the phone manufacturer could install other search, maps, or email apps in addition to those offered by Google. But multiple apps are duplicative, confusing to users, and a drain on limited device resources. Moreover, in the key categories of search and location, Google requires that its apps be the default, and Google demands prominent placements for its search app and app store. These factors sharply limit users’ attention to other preloaded apps, reducing competitors’ willingness to pay for preinstallation. Thus, even if phone manufacturers or carriers preload multiple applications in a given category, the multiple apps are unlikely to significantly weaken the effects of the tie.

These MADA restrictions suppress competition. Thanks to the MADA, alternative vendors of search, maps, location, email, and other apps cannot outcompete Google on the merits; even if a competitor offers an app that’s better than Google’s offering, the carrier is obliged to install Google’s app also, and Google can readily amend the MADA to require making its app the default in the corresponding category (for those apps that don’t already have this additional protection). Furthermore, competitors are impeded in using the obvious strategy of paying manufacturers for distribution; to the extent that manufacturers can install competitors’ apps, they can offer only inferior placement adjacent to Google, with Google left as the default in key sectors—preventing competitors from achieving scale or outbidding Google for prominent or default placement on a given device.

These MADA restrictions harm consumers. One direct harm is that competing app vendors face greatly reduced ability to subsidize phones through payments to manufacturers for preinstallation or default placement; Google’s rules leave manufacturers with much less to sell. Furthermore, these restrictions insulate Google from competition. If competing vendors were nipping at Google’s heels, Google would be forced to offer greater benefits to consumers—perhaps fewer ads or greater protections against deceptive offers. Instead, the MADA restrictions increase Google’s confidence of outmaneuvering competitors—insulating Google from the usual competitive pressures.

One might reasonably compare these MADA restrictions to other recent Google rules — also secret — apparently requiring phone manufacturers to install only a recent version of Android if they want to install Google apps (even if the apps run on earlier versions, which in general they do). But there are plausible pro-consumer benefits for Google to require that manufacturers move to the latest version of Android, including facilitating upgrades and coordinating platform usage on the latest version of Android. In contrast, there are no plausible pro-consumer benefits to the Google MADA restrictions I analyze above. For example, consumers do not benefit when Google prevents phone manufacturers from installing apps in whatever combination consumers prefer.

Little Prior Public Understanding of Google’s Restrictions on Phone Manufacturers

To date, these MADA restrictions have been unknown to the public. Meanwhile, Google’s public statements indicate few to no significant restrictions on use of the Android operating system or Google’s apps for Android—leading reasonable observers and even industry experts to conclude, mistakenly, that Google allows its apps to be installed in any combination that manufacturers prefer.

For example, on the “Welcome to the Android Open Source Project!” page, the first sentence touts that “Android is an open source software stack.” Nothing on that page indicates that the Android platform, or Google’s apps for Android, suffer any restriction or limitation on the flexibility standard for open source software.

Moreover, senior Google executives have emphasized the importance of Google’s openness in mobile. Google SVP Jonathan Rosenberg offered a 4300-word analysis of the benefits of openness for Google generally and in mobile in particular. For example, Rosenberg argued: “In an open system, a competitive advantage doesn’t derive from locking in customers, but rather from understanding the fast-moving system better than anyone else and using that knowledge to generate better, more innovative products.” Rosenberg also argued that openness “allow[s] innovation at all levels—from the operating system to the application layer—not just at the top”—a design which he said helps facilitate “freedom of choice for consumers” as well as “competitive ecosystem” for providers. Rosenberg says nothing about MADA provisions or restrictions on what apps manufacturers can install. I see no way to reconcile the MADA restrictions with Rosenberg’s claim of “allow[ing] innovation at all levels” and claimed “freedom of choice for consumers.”

Andy Rubin, then Senior Vice President of Mobile at Google, in 2011 claimed that “[D]evice makers are free to modify Android to customize any range of features for Android devices.” He continued: “If someone wishes to market a device as Android-compatible or include Google applications on the device, we do require the device to conform with some basic compatibility requirements [hyperlink in the original]. (After all, it would not be realistic to expect Google applications—or any applications for that matter—to operate flawlessly across incompatible devices).” Rubin’s post does not explicitly indicate that the referenced “basic compatibility requirements” are the only requirements Google imposes, but that’s the natural interpretation. Reading Rubin’s remarks, particularly in light of his introduction that Android is “an open platform,” most readers would conclude that there are no significant restrictions on app installation or search defaults.

Google Chairman Eric Schmidt offered particularly far-reaching remarks on Google’s rules about mobile apps and search defaults. After a 2011 Senate hearing about competition in online search, Senator Kohl asked Schmidt (question 8.a):

Has Google demanded that smartphone manufacturers make Google the default search engine as a condition of using the Android operating system?

Schmidt responded:

Google does not demand that smartphone manufacturers make Google the default search engine as a condition of using the Android operating system. …

One of the greatest benefits of Android is that it fosters competition at every level of the mobile market—including among application developers. Google respects the freedom of manufacturers to choose which applications should be pre-loaded on Android devices. Google does not condition access to or use of Android on pre-installation of any Google applications or on making Google the default search engine. …

Manufacturers can choose to pre-install Google applications on Android devices, but they can also choose to pre-install competing search applications like Yahoo! and Microsoft’s Bing. Many Android devices have pre-installed the Microsoft Bing and Yahoo! search applications. No matter which applications come pre-installed, the user can easily download Yahoo!, Microsoft’s Bing, and Google applications for free from the Android Market.

Schmidt’s response to Lee (question 15.b), to Franken (question 7), and to Blumenthal (question 7) were similar and, in sections, verbatim identical.

Taken on its own, Schmidt’s statement seems to offer a categorical denial that Google in any way restricts what apps manufacturers and carriers install. But in fact Schmidt’s statement is much narrower. For example, reread Schmidt’s assertion that “Google does not condition access to or use of Android on pre-installation of any Google applications or on making Google the default search engine.” The natural interpretation is that no Google rule requires manufacturers to preinstall any Google app or make Google the default search. But Schmidt actually leaves open the possibility that some other Google-granted benefit, other than permission to use Android, imposes exactly these requirements. Indeed, the above-referenced documents reveal that Google imposes these requirements if a manufacturer seeks any of the listed Google apps. But Schmidt’s statement indicates nothing of the sort.

Similarly, notice the ambiguity in Schmidt’s statement that “Manufacturers can choose to pre-install Google applications on Android devices, but they can also choose to pre-install competing search applications like Yahoo! and Microsoft’s Bing.” The clear implication is that manufacturers can pre-install Google, Yahoo, Microsoft, and other applications in any combination they choose. But her too, Schmidt’s carefully-worded response is narrower. Specifically, Schmidt indicates that manufacturers can install Google apps or they can install competitors’ apps. With the benefit of the above-referenced MADA, we see the gaps in Schmidt’s representation—leaving open the possibility that, as the MADA reveals, the choice is all-or-nothing. Yet ordinary readers have no reason to suspect the possibility of an all-or-nothing choice, and Schmidt’s response does nothing to suggest any such requirement. Schmidt’s statements—at best incomplete, and I believe affirmatively misleading—gave the senators and the general public a mistaken sense that Google apps and competing apps could be installed in any combination.

Even when industry experts have inquired, they have struggled to uncover Google’s true rules for mobile app preinstallations. Consider the September 2012 post entitled Google Doesn’t Require Google Search On Android by Danny Sullivan, arguably the web’s leading search engine expert. In that analysis, Sullivan consults publicly available sources to attempt to determine whether Google allows Android manufacturers to change Android default search while installing other Google apps. Finding no prohibition in any available document, Sullivan tentatively concludes that such changes are permitted. Sullivan clearly recognizes the difficulty of the question—he resorts to four separate postscripts as he consults additional sources. But with no document indicating that Google imposes any such restriction, Sullivan has no grounds to conclude that such a restriction exists. As it turns out, Sullivan’s conclusion is manifestly contrary to the plain language of the MADA: Sullivan concludes, for example, that a carrier could configure phones to “use the Android app store if [the carrier] made Bing [Search] the default.” In fact, a manufacturer must accept a MADA in order to obtain App Store access, and MADA Section 3.4(4) then imposes the requirement that Google Search be the default search at all web access points. But Sullivan had no access to a MADA, and MADA provision 6.1 prohibited manufacturers from telling Sullivan about MADA terms. No wonder Sullivan concluded there was no such restriction.

Similarly, when tech journalist Charles Arthur examined “why Google Android software is not as free or open-source as you may think,” he had to resort to unnamed sources and inferences from publicly-available materials. Arthur’s hypothesis was correct. But by keeping MADA’s secret, Google prevented Arthur from substantiating his allegations.

In principle, the public could have learned about MADA provisions through periodic company disclosures of key supplier contracts. Indeed, in 2011 Motorola circulated a redacted MADA as an exhibit to an SEC filing. But Motorola removed crucial provisions from the public version of this document. For example, the redacted Motorola MADA removes the most important sentence of MADA section 2.1—leaving only a placeholder where the original document stated “Devices may only be distributed if all Google Applications … are pre-installed.” Thus, even if a reader is savvy enough to find this SEC filing, the MADA’s key provisions remain unavailable.

MADA secrecy advances Google’s strategic objectives. By keeping MADA restrictions confidential and little-known, Google can suppress the competitive response. If users, app developers, and the concerned public knew about MADA restrictions, they would criticize the tension between the restrictions and Google’s promise that Android is “open” and “open source.” Moreover, if MADA restrictions were widely known, regulators would be more likely to reject Google’s arguments that Android’s “openness” should reduce or eliminate regulatory scrutiny of Google’s mobile practices. In contrast, by keeping the restrictions secret, Google avoids such scrutiny and is better able to continue to advance its strategic interests through tying, compulsory installation, and defaults.

Relatedly, MADA secrecy helps prevent standard market forces from disciplining Google’s restriction. Suppose consumers understood that Google uses tying and full-line-forcing to prevent manufacturers from offering phones with alternative apps, which could drive down phone prices. Then consumers would be angry and would likely make their complaints known both to regulators and to phone manufacturers. Instead, Google makes the ubiquitous presence of Google apps and the virtual absence of competitors look like a market outcome, falsely suggesting that no one actually wants to have or distribute competing apps.

Tying to Benefit Google’s Other Services

If a phone manufacturer wants to offer desired Google functions without close substitutes, the MADA provides that the manufacturer must install all other Google apps that Google specifies, including the defaults and placements that Google specifies. These requirements are properly understood as a tie: A manufacturer may want YouTube only, but Google makes the manufacturer accept Google Search, Google Maps, Google Network Location Provider, and more. Then a vendor with offerings only in some sectors—perhaps only a maps tool, but no video service—cannot replace Google’s full suite of services.

I have repeatedly flagged Google using its various popular and dominant services to compel use of other services. For example, in 2009-2010, to obtain image advertisements in AdWords campaigns, an advertiser had to join Google Affiliate Network. Since the rollout of Google+, a publisher seeking top algorithmic search traffic de facto must participate in Google’s social network. In this light, numerous Google practices entail important elements of tying:

| If a ___ wants ___ | Then it must accept ___ |

| If a consumer wants to use Google Search | Google Finance, Images, Maps, News, Products, Shopping, YouTube, and more |

| If a mobile carrier wants to preinstall YouTube for Android | Google Search, Google Maps (even if a competitor is willing to pay to be default) |

| If an advertiser wants to advertise on any AdWords Search Network Partner | All AdWords Search Network sites (in whatever proportion Google specifies) |

| If an advertiser wants to advertise on Google Search as viewed on computers | Tablet placements and, with limited restrictions, smartphone placements |

| If an advertiser wants image ads | Google Affiliate Network (historic) |

| If an advertiser wants a logo in search ads | Google Checkout (historic) |

| If a video producer wants preferred video indexing | YouTube hosting |

| If a web site publisher wants preferred search indexing | Google Plus participation |

Looking at Google’s dominance, many critics focus on Google’s power in search and search advertising. But this table shows the breadth of Google’s dominant services and the many ways in which Google uses its dominant services to cause usage of its less popular offerings.

I do not claim that tying always makes Google’s products succeed. Weak offerings, strong competition, and competitors’ network effects can all still stand in the way. But by tying its offerings in these ways detailed above, Google increases the likelihood that its offerings will succeed. One might reasonably ask, for example, what chance Google Checkout should have had: Reaching users a decade after Paypal and competing with Paypal’s huge user base, by ordinary measures Checkout should have been entirely stillborn. Indeed Checkout’s growth has been slow. But what would have happened if, rather than featuring a special logo only for AdWords advertisers who joined Checkout, Google had shown such logos for all popular payment intermediaries? Surely equal treatment of Checkout versus competitors would have reduced Checkout’s adoption and harmed Checkout’s relative prospects. Yet equal treatment would have provided consumers with timely and actionable information, and would have facilitated genuine competition on the merits.

Google used a similar technique in its 2003 launch of AdSense. At the time, advertisers largely sought Google’s AdWords placements within Google’s search engine. Upon launching AdSense, Google required advertisers to accept placements through Google’s new contextual network. These placements offered additional exposure which some advertisers surely valued. But publishers have an obvious incentive to commit click fraud—increasing the amount that Google pays to advertisers, but at the same time inflating advertisers’ costs. Furthermore, some publishers present material that advertisers would not want to be associated with (such as adult material and copyright infringement). Many advertisers would have declined to participate in the contextual network had they been asked to make a decision one way or the other. By insisting that advertisers accept such placements, Google gave itself instant scale—hence ample resources to pay publishers and outbid other networks seeking space on publishers’ sites. In contrast, competing ad platforms had to recruit skeptical advertisers through long sales pitches, performance guarantees, and lower prices—yielding fewer advertisers, lower payments to publishers, and a weaker competitive position. No wonder AdSense achieved scale while competitors struggled—but Google’s success should be attributed as much to the tie as to the genuine merits of Google’s offering.

In a forthcoming article, I’ll explore these and other contexts in which Google ties its services together. Applicable antitrust law can be complicated: Some ties yield useful efficiencies, and not all ties reduce welfare. But Google’s use of tying gives it a leg up in numerous markets that would otherwise enjoy vibrant competition. Given Google’s dominance in so many sectors, this practice deserves a closer look.