The anti-spyware community has been abuzz all weekend with the news of spyware company 180solutions joining the Consortium of Anti-Spyware Technology (COAST). From the 180solutions press release:

“180solutions, a provider of search marketing solutions, today announced it has become a developer member of … COAST. … By working with COAST and complying with its strict Code of Ethics, standards and guidelines, 180solutions aligns itself with the organization’s governing companies, … PestPatrol, … Webroot. … “180solutions has passed a lengthy and rigorous review process demonstrating their commitment to develop and distribute spyware-free applications,” said Trey Barnes, executive director of COAST.”

Some specific worries:

Substantive conflict of commitment

COAST members PestPatrol and Webroot currently detect and remove 180 software. So these companies are (rightly!) telling their users that 180solutions software should be removed from users’ computers.

At the same time, according to 180’s press release, 180solutions is “releasing versions of its applications that have been reviewed and evaluated by COAST.” This press release, COAST’s “review” of 180 software, and COAST’s acceptance of 180 into its consortium can only be taken to constitute a COAST endorsement of 180. That’s a clear conflict with COAST members simultaneously recommending that users remove 180 software.

Then there’s the conflict of interest that inevitably arises whenever an anti-spyware company declares an alleged spyware provider to be legitimate. Users buying a vendor’s anti-spyware software think they’re buying that vendor’s best efforts to identify and remove software users don’t want. When the vendor instead accepts funds from a software provider, one making the kind of software that the vendor is supposed to be removing, users can’t help but wonder whose interests the vendor has in mind. To my mind, the better strategy is for anti-spyware vendors to refuse partnerships with any company making software that might colorably be claimed to be spyware. (See Xblock’s statement of policy.)

I don’t want to overstate the problem. So far, PestPatrol and Webroot still detect and remove 180 software. 180 isn’t listed on COAST’s Members page. And COAST members don’t directly receive the money 180 pays COAST.

But the latent problems remains: For a fee, COAST is certifying controversial providers of allegedly-unwanted software, dramatically complicating the role and duties of COAST and its members. COAST staff are providing favorable quotes in 180 press releases. Who can users trust?

180solutions installation practices are outrageous and unethical

180’s endorsement by COAST is particularly puzzling and particularly worrisome due to 180’s many bad business practices. Indeed, in my testing, 180’s installation practices remain among the worst in the industry. The details:

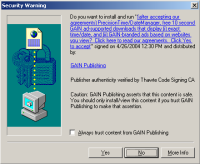

I have personally observed (and preserved in video recordings) more than two dozen instances of 180 software installed through security holes. (Example video.) Just yesterday, I browsed the Innovations of Wrestling site (iowrestling.com, proceed at your own risk), where viewing the site’s privacy policy invoked a security exploit installing more than a dozen unwanted programs, 180solutions software included. (Note that iowrestling’s installations are at least partially random, so it’s hard to replicate this result. But I kept a video and packet log of my findings.)

Even when 180 installers do request consent to install, the disclosure is often quite misleading. For example, I previously documented Kiwi Alpha installing 180, first mentioning 180 at page 16 of a 54-page license agreement. With 180’s installation warning buried in such a long text, ordinary users are unlikely to learn that Kiwi gives them 180. Certainly users don’t grant knowing consent to the installation.

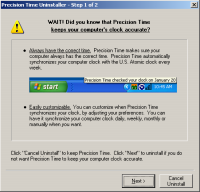

180’s web site claims “no hiding,” but 180 uses a variety of tricks to make its software harder to find and remove. 180 sometimes uses randomized filenames which make its files unusually difficult to locate. 180 also installs itself into multiple directories — sometimes c:Program Files180solutions (or similar), but sometimes into the root of c:Program Files and sometimes directly into a user’s Windows directory. If uses do manage to find and delete some 180 files, another 180 program often pops up to request reinstallation. If these tricks don’t constitute hiding, I don’t know what does.

180’s controversial installation practices are not mere anomalies. I’ve observed these, and others like them, for months on end. Even 180solutions’ director of marketing sees the problem. See Seattle Post-Intelligencer article, reporting his admission that “n-Case could get bundled with other free software programs without the company’s knowledge [which] could lead to the n-Case software fastening to individual’s computers without their knowledge.”

How did 180 get into this mess? It seems 180 hasn’t been careful in choosing who they partner with. In fact, they recruit distributors (as well as advertisers) by unsolicited commercial email. See 20+ examples.

Interestingly, in its recent press release, 180 does not claim to have stopped these controversial practices. If 180 did make such a claim, I’d be able to disprove it easily — there are so many sources of 180 software installed without notice and consent. Instead, 180 claims only that they are working on a “transition” to improved business practices.

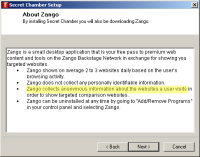

But this isn’t the first time 180 has promised to clean up its act. In March 2004, 180’s CEO claimed 180’s “Zango” product — then the new replacement for the older n-CASE — would give users more information before installation. In an April interview, he attributed to the old n-CASE product “certain users … who are not sure where or how they got our software,” but said “the Zango product … is a means to improve that.” On at least these two occasions, 180 has pledged to improve its practices. Nearly a year later, 180 software often still gets installed without notice or consent. So we’re still waiting for the promised improvements. Meanwhile, 180 continues to benefit profit from its millions of ill-gotten installations.

180solutions advertising practices are outrageous and unethical

Beyond controversial installation methods, 180 also deserves criticism for its intrusive and allegedly-anticompetitive advertising practices.

When 180 covers a web site with one of its competitors, 180 doesn’t just show a small popup ad (like, say, Claria — not that Claria’s practices deserve praise). Instead, 180 opens a new web browser showing the competitor’s site, generally covering substantially all of the targeted web site. A user who wants to stick with the site he had previously requested must affirmatively close the new window — taking an extra step due to 180’s intervention. What would we think of a telephone company that connects a user to Gateway when the user dials 1-800-Dell-4-Me, unless the user then presses some extra key to return to what he had requested initially? The real-world analogy makes it almost too easy to assess 180’s legitimacy: No telephone company could get away with such a scam, yet 180’s advertising practices have gone largely unchallenged.

Even more problematic are 180 ads targeted at competitors’ check-out pages. Sometimes 180 lets a user browse a merchant’s web site uninterrupted, but when the user reaches the page requesting order confirmation, 180 then covers the merchant’s site with a competitor — interrupting the user’s purchase. Again, the real-world analogy is straightforward. Suppose one retailer sent its sales employees into a competitor’s store, to invite users to take their business elsewhere as they waited in line to reach the checkout counter. The intruding employees would be arrested as trespassers.

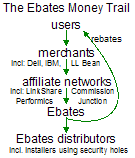

Then there are the thousands of 180 ads that include affiliate codes. Some of 180’s ads cover a web site with a competitor reached through an affiliate link. Via these ads, companies find themselves promoted by 180, and find themselves directly or indirectly paying commissions to 180 — all despite never requesting that 180 advertise or promote them.

Even worse are the 180 ads that target a merchant with its own affiliate links. Here, merchants end up paying affiliate commissions where they’re not otherwise due. For example, when users reach merchants’ sites by clicking through non-affiliate links or by typing merchants’ domain names, 180 nonetheless intercedes by opening affiliate links to merchants’ sites. Whether shown in double windows, hidden windows, or on-screen decoys, 180’s affiliate links make merchants’ commission-tracking systems think resulting purchases resulted from 180’s promotional efforts. Unless merchants figure out that they’re being cheated — being asked to pay commissions not fairly earned — 180 and its advertisers receive commission payments for users’ purchases. (Details; example.)

There’s plenty more to criticize about 180. To this day, installations on zango.com let users install 180 software without so much as seeing 180’s license agreement. Even 180’s current uninstall procedures give far more information than 180 provides prior to installation. And Andrew Clover reported 180 code that deletes competitors’ programs from users’ disks.

COAST’s credibility on the line

180’s claims of planned improvement are essentially unverifiable. Since 180 admits to a mix of permissible and impermissible installations, its claims of improvement cannot be falsified by critiquing current behavior. Instead, whenever I or others show 180 software installed without proper notice and consent, 180 can say this is just a remnant of prior practices not yet cleaned up in “transition.” By the plain text of 180’s press release, we’ll have to wait at least 90 days to prove that 180 isn’t living up to its promises to COAST and to users.

Why would COAST sign onto this bargain? MediaPost reports 180 paying COST a membership fee as large as $10,000 per year, so that gives one clear explanation. Also, notwithstanding participation by PestPatrol and Webroot, COAST’s past is hardly uncontroversial. In 2003, Lavasoft (makers of Ad-Aware) decided to leave COAST, complaining that COAST’s focus on “revenue generation … reflect[s] badly on the entire anti-trackware industry.” Similarly, Spybot refused to join COAST due to participation by companies that were, in Spybot’s view, unethical.

COAST’s credibility is on the line. I don’t see endorsement of software providers as an appropriate part of COAST’s mission. But even if such work were appropriate, 180 deserves no such praise — its history of outrageous practices and its continued use of such practices mean it should be criticized, not granted an award or endorsement.

Update (February 4): Reporting “concern” at COAST’s certification program, Webroot resigned from COAST.

Update (February 7): Computer Associates (makers of PestPatrol) also resigned from COAST. However, a CA spokesperson defended COAST’s endorsement procedure, calling such endorsements “valuable.”

Disclosure: I serve as a consultant to certain merchants concerned about fraudulent activities by 180solutions and its advertisers. I have advised certain attorneys and merchants concerned about 180solutions activities and practices.

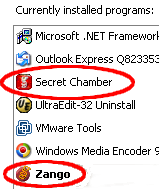

Screen-shot showing that when Zango comes with Secret Chamber, Zango receives a separate entry in Add/Remove Programs. Claria’s Gator, in contrast, lacks such an entry.

Screen-shot showing that when Zango comes with Secret Chamber, Zango receives a separate entry in Add/Remove Programs. Claria’s Gator, in contrast, lacks such an entry.

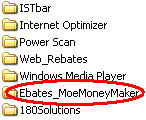

Screen-shot of my Program Files folder, showing some of the programs installed on my test computer.

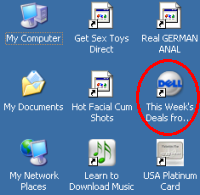

Screen-shot of my Program Files folder, showing some of the programs installed on my test computer. Screen-shot of the icons added to my test computer’s desktop. Note a new link to Dell — an affiliate link such that Dell pays commissions when users make purchases after clicking through this link.

Screen-shot of the icons added to my test computer’s desktop. Note a new link to Dell — an affiliate link such that Dell pays commissions when users make purchases after clicking through this link. Partial screen-shot taken from video of Ebates installation through a security hole, without any notice or consent.

Partial screen-shot taken from video of Ebates installation through a security hole, without any notice or consent. For users who share my continued interest in

For users who share my continued interest in  Malware installed through a single security exploit

Malware installed through a single security exploit