The usual motive for buying spyware popup traffic is simple: Showing ads. Cover Netflix’s site with an ad for Blockbuster, and users may buy from Blockbuster instead. Same for other spyware advertisers.

But there are other plausible reasons to buy spyware traffic. In particular, cheap spyware traffic can be used to inflate a site’s traffic statistics. Buying widespread “forced visits” causes widely-used traffic measurements to overreport a site’s popularity: Traffic measurements mistakenly assume users arrived at the site because they actually wanted to go there, without considering the possibility that the visit was involuntary. Nonetheless, from the site’s perspective, forced visits offer real benefits: Investors will be willing to pay more to buy a site that seems to be more popular, and advertisers may be willing to pay more for their ads to appear. In some sectors, higher reported traffic may create a buzz of supposed popularity — helping to recruit bona fide users in the future.

Yet spyware-originating forced-visit traffic can cause serious harm. Harm may accrue to advertisers — by overcharging them as well as by placing their ads in spyware they seek to avoid. Harm may accrue to investors, by causing them to overpay for sites whose true popularity is less than traffic statistics indicate. In any event, harm accrues to consumers and to the public at large, through funding of spyware that sneaks onto users’ PCs with negative effects on privacy, reliability, and performance.

Others have previously investigated some of these problems. In December 2006, the New York Times reported that Nielsen/NetRatings cut traffic counts for Entrepreneur.com by 65% after uncovering widespread forced site visits. But forced-visit traffic is more widespread than the four specific examples the Times presented.

This article offers six further examples of sites receiving forced visits — including the spyware vendors and ad networks that are involved. The article concludes by analyzing implications — suggested policy responses for advertisers and ad networks, as well as ways of detecting sites receiving forced visits.

Example 1: IE Plugin and Paypopup Promoting Bolt.com

IE Plugin Promoting Bolt.com

IE Plugin Promoting Bolt.com

In testing of April 23, I browsed Google and received the popunder shown at right (after activation) and in video. Packet log analysis reveals that traffic flowed as follows: From IE Plugin (purportedly of Belize), to Paypopup (of Ontario, Canada), to Paypopup’s multi-pops.com ad server, to Bolt (of New York). URLs in the sequence:

http://66.98.144.169/redirect/adcycle.cgi?gid=9&type=ssi&id=396

http://paypopup.com/adsDirect.php?cid=1133482&ban=1&id=ieplugin&sid=10794&pub…

http://service.multi-pops.com/adsDirect.php?ban=1&id=ieplugin&cid=1133482&sid…

http://service.multi-pops.com/links.php?data=rSe_2%2F%FE%2F1%285%FE1%2F%2B%24…

http://service.multi-pops.com/linksed.php?sn=851177371957&uip=…&siteid=iepl…

http://www.bolt.com/

As shown in the packet log, this traffic originated with IE Plugin’s Adcycle.cgi ad-loader. This ad-loader sends traffic to a variety of ad networks, as best I can tell without any targeting whatsoever. Users therefore receive numerous untargeted ad windows, typically appearing as popups and popunders.

The resulting Bolt window appears without any attribution or branding indicating what spyware caused it to appear. This lack of labeling makes it particularly hard for users to figure out what program is responsible or to take action to stop further unwanted ads. IE Plugin’s unlabeled ads are particularly harmful because users may not have authorized the installation of IE Plugin in the first place: I have repeatedly seen IE Plugin install without user consent, including via bundles assembled by notorious spyware distributor Dollar Revenue.

The packet log indicates that Bolt purchased traffic not from IE Plugin directly, but rather from Paypopup. But Paypopup’s name and product descriptions specifically indicate the kind of ads that Paypopup sells forced visits — popups that appear without an affirmative end-user choice. The inevitable result of such traffic purchases is to inflate the measured popularity of the beneficiary web sites. So even if Bolt did not know it was buying spyware-originating advertising, Bolt must have known it was receiving forced visit traffic.

The packet log also shows that Paypopup specifically knew it was doing business with IE Plugin. Notice the repeated references to IE Plugin in the Paypopup and Multi-pops ad-loader URLs (“id=ieplugin”).

Bolt’s “About” page includes a claim of “reach[ing] 14.9 million unique visitors each month.” Taking this claim at face value, Bolt’s relationship with Paypopup and IE Plugin begs the question: How many of Bolt’s visitors are forced to see Bolt because spyware took them there, rather than because they affirmatively chose it?

Meanwhile, Bolt boasts top-tier advertisers including Verizon (shown in part in the screenshot above), Coca-Cola, Nike, and Sony. These brand-conscious advertisers are unlikely to want their ads to appear through spyware-delivered popups.

Example 2: Yourenhancement, Adtegrity, Right Media Exchange, and AdOn Network (MyGeek) Promoting PureVideo Networks’ GrindTV

Yourenhancement Promoting GrindTV

Yourenhancement Promoting GrindTV

In testing of April 29, I browsed the web and received the full-screen popup shown at right. The popup was so large and so intrusive that it even covered the Start Menu, Taskbar, and System Tray — preventing me from easily switching to another program.

Packet log analysis reveals that traffic flowed as follows: From Yourenhancement (of Los Angeles), to Adtegrity (of Grand Rapids, Michigan), to the Right Media Exchange, to AdOn Network (previously MyGeek/Cpvfeed) (of Phoenix, Arizona) to Grind TV (of El Segundo, California). URLs in the sequence:

http://63.123.224.168/mbop/display.php3?aid=19&uid=…

http://ad.adtegrity.net/imp?z=0&Z=0x0&s=4670&u=http%3A%2F%2F63.123.224.168…

http://ad.yieldmanager.com/imp?z=0&Z=0x0&s=4670&u=http%3A%2F%2F63.123.224….

http://ad.adtegrity.net/iframe3?AAAAAD4SAADV5AMAtnIBAAIADAAAAP8AAAABEwACAA…

http://ad.yieldmanager.com/iframe3?AAAAAD4SAADV5AMAtnIBAAIADAAAAP8AAAABEwA…

http://campaign.cpvfeed.com/cpvcampaign.jsp?p=110459&campaign=Mortgage&aid…

http://www.grindtv.com/p/hs444/mygeek/

Yourenhancement’s display.php3 ad-loader sends traffic to a variety of ad networks, by all indications without any targeting whatsoever. Users therefore receive numerous untargeted popups and popunders. As in the prior example, the resulting window lacks any branding to indicate what spyware caused it to appear or how users can prevent future popups from the same source.

Yourenhancement’s unlabled ads are particularly harmful because users may not have authorized the installation of Yourenhancement in the first place: I have repeatedly seen Yourenhancement install without user consent — including in bundles assembled by DollarRevenue, in WMF exploits served from ExitExchange, in misleading ActiveX bundles packaged by IE Plugin, and in a CoolWebSearch exploit served from Runeguide.

The packet log indicates that GrindTV purchased traffic not from Fullcontext directly, but rather from AdOn Network. However, advertising professionals should know that buying advertising from AdOn Network inevitably means receiving traffic from spyware. For example, Direct Revenue’s site previously disclosed that Direct Revenue shows AdOn ads, while AdOn’s site admitted showing ads through both Direct Revenue (“OfferOptimizer”) and Zango (180solutions). My site has repeatedly covered AdOn’s role in spyware placements (1, 2, 3, 4). I continue to observe traffic flowing directly to MyGeek from various spyware installed without user consent, including Look2me and Targetsaver. With voluminous documentation freely available, advertisers cannot reasonably claim not to know what kind of ads AdOn sells.

The GrindTV site is operated by PureVideo Networks. I have previously seen spyware-originating forced visits to other PureVideo sites, including Stupidvideos.com and Hollywoodupclose.com.

PureVideo’s “News” page specifically touts the company’s reported popularity (“among top 10 US video sites by market share”, “top growing sites”, “StupidVideos Climb Charts”, etc.). In March, ComScore even announced that PureVideo sites were the ninth-fastest growing properties on the web. But in that same month, I observed widespread forced-visit promotion of multiple PureVideo sites. Forced visits can easily cause a dramatic traffic jump — the same occurrence ComScore reported. It’s hard to know whether PureVideo’s forced visits inflated ComScore’s measurements of PureVideo’s popularity, but that seems like a plausible possibility, particularly in light of Nielsen/NetRatings’ 2006 cut of Entrepreneur’s traffic (after Entrepreneur had used similar tactics).

PureVideo’s Investors & Advisors page indicates that PureVideo has received outside investment, including a $5.6 million investment from SoftBank Capital.

Example 3: Yourenhancement, Adtegrity, Right Media Exchange, and AdOn Network (MyGeek) Promoting Broadcaster.com

Yourenhancement Promoting Broadcaster

Yourenhancement Promoting Broadcaster

In testing of April 29, I browsed the web and received the popup shown at right.

Packet log analysis reveals that traffic flowed as follows: From Yourenhancement (widely installed without consent, as set out above) to Adtegrity, to the Right Media Exchange, to AdOn Network to Broadcaster (of Las Vegas). URLs in the sequence:

http://63.123.224.168/mbop/display.php3?aid=18&uid=…

http://ad.adtegrity.net/imp?z=0&Z=0x0&s=113743&u=http%3A%2F%2F63.123.224.1…

http://ad.yieldmanager.com/imp?z=0&Z=0x0&s=113743&u=http%3A%2F%2F63.123.2….

http://ad.adtegrity.net/iframe3?AAAAAE-8AQBJ6wQARMcBAAIACAAAAP8AAAABEwACAA…

http://ad.yieldmanager.com/iframe3?AAAAAE-8AQBJ6wQARMcBAAIACAAAAP8AAAABEwA…

http://campaign.cpvfeed.com/cpvcampaign.jsp?p=110495&campaign=121kwunique&…

http://url.cpvfeed.com/cpv.jsp?p=110495&aid=501&partnerMin=0.0036&…

http://www.broadcaster.com/tms/video/index.php?show=trated&bcsrtkr=a85d2&u…

As in the preceding example, traffic originated with Yourenhancement’s display.php3 ad-loader, and lacked any branding to indicate its source. The preceding example reports some of the many contexts in which Yourenhancement has become installed on my test PCs without my consent.

The packet log indicates that GrindTV purchased traffic from AdOn. But as the preceding example explains, Broadcaster should reasonably have known that buying traffic from AdOn means receiving forced-visit traffic as well as spyware-originating traffic.

Broadcaster has recently issued press releases to promote its increased traffic (“Broadcaster traffic rankings soar … one of the fastest growing online entertaining communities”; “88% increase in month-over-month website traffic”; “Tremendous audience growth”; etc.). So Broadcaster clearly views its traffic statistics as important. Yet nowhere in Broadcaster’s press releases does Broadcaster mention that its reported visitor counts include visitors who arrived involuntarily.

Broadcaster is a publicly traded company (OTC: BCSR.OB). Broadcaster’s December 2006 SEC 10KSB/A disclosure does briefly discuss Broadcaster’s purchase of “online advertisements … to attract new users” to its service. But the word “advertisements” tends to suggest mere solicitations (e.g. banner ads), not full impressions that cause a loading of Broadcaster’s site (and hence a tick in reported traffic figures). In my review of this and other Broadcaster financial documents, I could find no direct admission that Broadcaster buys cheap forced visits, then counts those involuntary visits towards records of site popularity. It appears that investors may be buying shares in Broadcaster without understanding the true origins of at least some of Broadcaster’s traffic.

This is not Broadcaster’s first run-in with spyware. Broadcaster’s Accessmedia subsidiary was named as a co-defendant in FTC and Washington Attorney General 2006 suits against Movieland et al., alleging that defendants’ software “barrages consumers’ computers with pop-up windows demanding payment to make the pop-ups go away.” According to the FTC’s complaint, Broadcaster’s Accessmedia subsidiary served as the registrant and technical contact for Movieland.com, and also shared telephone numbers and customer service with Movieland.

Example 4: Web Nexus Promoting Orbitz’s Away.com

Web Nexus Promoting Orbitz’s Away.com

Web Nexus Promoting Orbitz’s Away.com

In testing of April 29, I browsed the web and received the full-screen popup shown at right. As in Example 2, the popup even covered the Start Menu, Taskbar, and System Tray — preventing me from easily switching to another program. Meanwhile, the ad appeared substantially unlabeled — with a small Web Nexus caption at ad bottom, but with the caption’s letters more than half off-screen.

Packet log analysis reveals that traffic flowed as follows: From Web Nexus (purportedly of Bosnia and Herzegovina) directly to Orbitz’s Away.com. URLs in the sequence:

http://stech.web-nexus.net/cp.php?loc=295&cid=9951709&u=bmV0ZmxpeC5jb20v&e…

http://stech.web-nexus.net/sp.php/9905/28779/295/9951709/527/

http://travel.away.com/District-of-Columbia/travel-sc-hotels-1963-District…

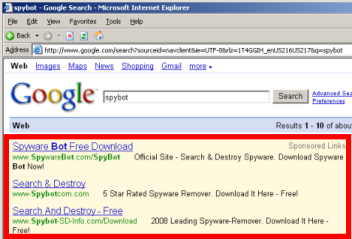

The packet log indicates that Away.com received traffic directly from Web Nexus. Web Nexus is well-known to be unwanted advertising software: The first page of Google search results for “Web Nexus” includes five references to spyware, four to adware, one to viruses, and six to user complaints seeking assistance with removal. I have personally observed Web Nexus becoming installed through a WMF exploit and through the DollarRevenue bundler, among other methods.

Orbitz’s Away.com popup provides three distinct business benefits to Orbitz. First, the popup promotes Orbitz’s own services (e.g. its hotel booking services). Second, the popup promotes Orbitz’s advertisers (here, Verizon, despite Verizon’s repeatedly–stated policy of not advertising through spyware). Finally, the popup inflates traffic statistics to Away.com — likely increasing advertisers’ future willingness to pay for ads at Away.com.

Example 5: WebBuying and Exit Exchange Promoting Roo TV

WebBuying Promoting Roo TV

WebBuying Promoting Roo TV

In testing of April 23, I browsed the web and received the full-screen popup shown at right. As in Example 2 and 4, the popup covered the Start Menu, Taskbar, and System Tray, and lacked readable labeling of its source.

Packet log analysis reveals that traffic flowed as follows: From WebBuying (a newer variant of Web Nexus) to ExitExchange to Roo TV. URLs in the sequence:

http://s.webbuying.net/e/sp.php/5ers7+aSiObv7uvm7e_v6e7o6e3m6erk

http://count.exitexchange.com/exit/1196612

http://ads.exitexchange.com/roo/?url=http://www.rootv.com/?channel=pop&f…

http://www.rootv.com/?channel=pop&fmute=true&bitrate=56

The packet log indicates that Roo TV received traffic directly from Exit Exchange — traffic that Exit Exchange reasonably should have known would include spyware-originating traffic. Exit Exchange widely receives spyware-originating traffic, passing from a variety of spyware to Exit Exchange, and onwards to Exit Exchange’s advertisers. (For example, in June 2006 I showed Exit Exchange receiving traffic from Surf Sidekick spyware, widely installed without consent. Meanwhile, SiteAdvisor rates Exit Exchange red for delivering exploits to users’ PCs — behavior I documented in February 2006 and observed twice last week alone.)

The Roo TV landing page URL leaves no doubt that Roo TV knew it was receiving forced visits. Notice the “channel-pop” tag in the URL log above — specifically conceding that the traffic at issue was not requested by users.

Roo TV’s “About” page reveals Roo’s emphasis on traffic quantity: The page’s first sentence boasts that “Roo is consistently ranked as one of the world’s ten most viewed online video networks.” But, as in the preceding examples, forced visits raise questions about how Roo got so popular. Is Roo a top-ten site in users’ minds, or only a destination users are frequently forced to visit, against their wishes?

Example 6: WebBuying Promoting Diet.com

WebBuying Promoting Diet.com

WebBuying Promoting Diet.com

In testing of April 23, WebBuying also served a full-screen popup of Diet.com — again covering the Start Menu, Taskbar, and System Tray, and again lacking readable labeling to disclose its source. Screen-capture video.

Packet log analysis reveals that traffic flowed from WebBuying directly to Diet:

http://c.webbuying.net/e/check.php?cid=13352451&lid=327&cc=US&u=aHR0cDov…

http://s.webbuying.net/e/sp.php/6+rv6uaSiObv7uvm7e_v6e7o6e3m6erk

http://www.diet.com/tracking/index.php?id=1052

As in the Away.com example, Diet.com receives several benefits from this popup: Promoting its own content, showing ads for third parties (here, Nutrisystem), and inflating its traffic statistics.

Alexa’s traffic statistics show a 5x+ jump in Diet traffic in early March — the same period in which I began observing forced visits to Diet.com.

Additional Examples on File

The preceding six examples are only a portion of my recent records of spyware-originating forced-visit I have recently observed. Under euphemisms that range from “audience development” to “push traffic,” these tactics have become widespread and, by all indications, continue to grow. I have seen other popups from each of these sites on numerous other occasions, and I have seen similar popups from other sites delivered via similar methods.

Implications & Policy Responses

Video sites are strikingly prevalent in the preceding examples and in other forced-visit traffic I have observed. Why? Google’s $1.65 billion acquisition of YouTube inspired others hoping to receive even a fraction of YouTube’s valuation. So far no competitor has gained much traction. But the expectation that video sites grow virally creates an incentive to try to jump-start traffic by any means possible — even spyware-originating traffic.

When forced-visit sites show ads, they tend to promote well-known advertisers. For example, two of the preceding examples (1, 4) feature Verizon, despite Verizon’s stated policy against spyware advertising. While concerned advertisers have generally added anti-spyware policies to their ad contracts, they still tend to ignore the problem of web sites buying spyware traffic. Verizon staff will probably take the position that it is not permissible for a Verizon ad to be shown in a site that receives widespread spyware traffic. But then Verizon’s ad contracts and other policy statements probably need to say so. Same for ad networks seeking to avoid reselling spyware inventory. In practice, few ad policies prohibit intermediary sites buying spyware-originating traffic.

Low-cost spyware-originating traffic can vastly increase a site’s reported popularity. Consider Alexa’s plot of Roo TV traffic. During April 2007 (when I first began to observe spyware-originating forced visits of Roo TV), Alexa reports that Roo’s reach and page views both jumped by an order of magnitude. It is difficult to know how much of this jump results from spyware-originating forced-visit traffic — rather than other kinds of forced visits, or conceivably bona fide user interest. But the New York Times piece reported that when ComScore last year adjusted Entrepreneur’s statistics to account for forced visits, traffic was reduced by 65%. A similar reduction may be required for the sites set out above.

When forced-visit sites show banner ads, the sites raise many of the same concerns as banner farms — including overwhelming advertising, unrequested popups, automatic reloads, opaque resale of spyware-originating traffic, and an overall bad value to advertisers. Particularly prominent among spyware-delivered banner farms is India Broadcast Live’s Smashits — which buys widespread spyware-originating forced-visit traffic, and shows as many as six different banner ads in a page that otherwise lacks substantial content. In some instances, Smashits’ page hijacks users’ browsers: Spyware removes the page a user had requested, and instead shows only the Smashits site. (Video example.) These practices may lead concerned advertisers and ad networks to avoid doing business with Smashits, including Smashits’ many alter egos and secondary domain names. But at present, Smashits continues to show ads from top advertisers and ad networks (particularly FastClick, Google, and TribalFusion). Same for other banner farms still in operation.

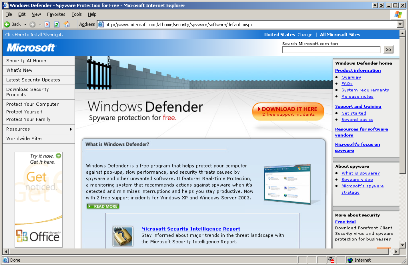

Detection

Sophisticated advertisers and ad networks rightly want to know which sites are buying spyware-originating forced-click traffic. But they can’t answer that question merely by examining individual sites: Bolt, GrindTV, and kin all look like ordinary sites, without any obvious sign that they get traffic from spyware. So advertisers and networks’ can’t catch spyware-originating traffic. using their usual techniques for evaluating publishers (such as browsing publishers’ sites in search of explicit or offensive materials).

Advertisers and ad networks might look for unusual changes in sites’ reported traffic rank — on the view that extreme spikes probably indicate forced-visit traffic. But there can be legitimate reasons for traffic spikes. Furthermore, an unexpected traffic jump will often prove an insufficient reason to block a prospective advertising relationship. Finally, if advertisers and ad networks distrusted sites with traffic spikes, sites could start their forced-click campaigns more gradually, to avoid tell-tale jumps. So checking for traffic spikes is not a sustainable strategy.

With help from traffic measurement vendors, advertisers and ad networks could attempt to measure visit length rather than visit count. But even visit length measurement might not prevent miscounting of spyware-originating forced visits. Some spyware opens sites off-screen — where JavaScript or other code could extend traffic indefinitely to inflate measured visit length as needed, without users noticing and closing the resulting windows.

The only robust way to detect spyware-originating forced visits is through testing of actual spyware-infected PCs — by watching their behavior and seeing what sites they show. Historically, I’ve done this testing manually, as in the examples set out above. Fortunately, detecting widespread spyware-originating traffic is easy — because, by hypothesis, the traffic is common and hence likely to appear even in brief testing. That said, a scalable automated system might be preferable to my hands-on testing. I’ve recently built an automatic tester that performs this function, among others. I’ll describe it more in a coming piece. US patent pending.

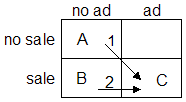

Revenue Counterfactual

Revenue Counterfactual