When unwanted programs (“spyware” and others) sneak onto users’ computers, their main goal is often to show extra ads, typically pop-ups. If a vendor’s program steals users’ credit card numbers or social security numbers, the vendor will get in real trouble. But, historically, software vendors have been able to show extra ads with impunity.

Where do these ads come from? What companies are willing to support the advertising software that users so despise? It turns out some of the world’s biggest companies are advertising in this way. In 2003, I posted a list of some of Gator’s then-biggest advertisers, work that PC Pitstop updated in 2003 (using Claria’s S1 filing). More recently, I’ve posted a list of substantially all eXact advertising advertisers. More to come.

These advertisers aren’t working in a vacuum. To the contrary, many of their ads appear through spyware only thanks to major ad intermediaries that facilitate and track those placements, and that assist in the associated payments.

Are ad intermediaries responsible when their ads are shown by software installed improperly? Marquette law professor Eric Goldman thinks not. But the New York Attorney General’s office has repeatedly suggested they might be. My take: Advertiser and intermediary liability is an interesting question of law, well beyond my aspirations for this brief piece. But where ad intermediaries purport to certify or stand behind the quality of the venues where their ads are shown, I’m not receptive to their claims that they can’t do what they’ve promised. Where ad intermediaries merely count advertisement clicks without even claiming to assure traffic quality, the case for blaming intermediaries for improper use of their tracking links may be somewhat weaker (though still cognizable).

One fact about which there is no reasonable dispute: Spyware would be far less profitable — and there would be far less of it trying to sneak onto users’ PCs — if big advertisers weren’t advertising this way and if big ad intermediaries weren’t helping to facilitate such advertisements.

An Initial Example: Atlas DMT Assisting with Expedia Ads Shown by 180solutions

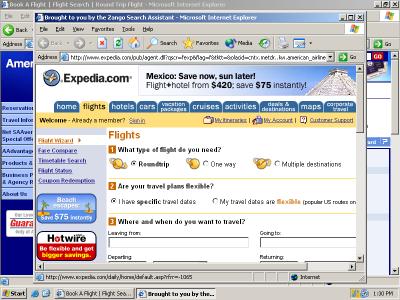

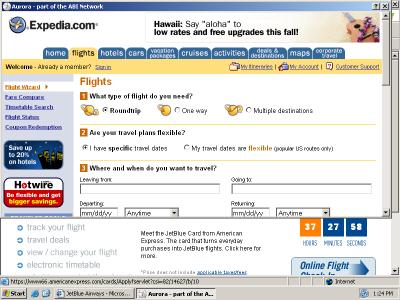

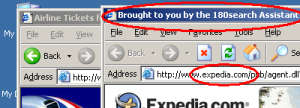

An Expedia ad shown by 180solutions, via Atlas DMT tracking

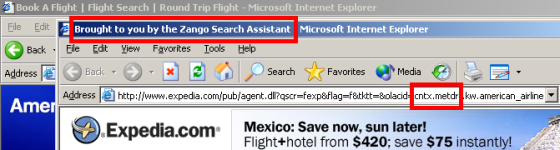

The many relationships in spyware advertising can be quite complicated, all the more so because advertising and payment structures take so many forms. But let me start with a relatively straightforward example: When users visit aa.com (American Airlines) on PCs with advertising software from 180solutions, 180 may show a popup of Expedia’s web site. See inset image at right.

Expedia

(advertiser)

viewers

viewers

Atlas DMT

(intermediary)

viewers

viewers

180solutions

Traffic Flow

Although 180 could show the Expedia site directly, traffic more typically passes through intermediaries like, in this case, aQuantive’s Atlas DMT. In particular, 180 invokes the Atlas tracking link http://expedia.click-url.com/ go/www18epd0600005172ave/ direct/01, which then redirects users to the specified page at Expedia. So users reach Expedia through Atlas, as shown in the diagram at right.

Ads are placed through intermediaries for a variety of reasons. Sometimes intermediaries help to broker the deal — making connections between advertisers and venues where ads can be shown. Some advertisers might not want to do business with 180solutions directly — maybe they haven’t heard of 180, or have heard only bad things; but doing business with Atlas seems reasonable thanks to Atlas’s better reputation. Or perhaps Atlas adds accountability: An advertiser might not trust 180’s record-keeping, but the advertiser might feel confident that Atlas will accurately count how many times each ad was shown. Intermediaries can also provide efficient and centralized payment, reducing administrative costs. Whatever the reason, ads tend to flow through intermediaries — and so intermediaries like Atlas are well-equipped to stop such ads from appearing, if they care to do so.

Of course this Expedia/Atlas example is but one of many. See e.g. a more detailed example I posted in July 2004, showing a 180solutions ad for Hawaiian Airlines ad, also served by Atlas, substantially covering the Delta.com site.

A Case Study: Advertising Intermediaries Supporting 180solutions

Beyond the Expedia ad shown above, I’ve also been looking at all 180’s other ads, along with examining where these ads come from.

For those interested in advertisers supporting unwanted software, 180solutions is a natural place to start. 180solutions is often installed with no consent at all (videos: 1, 2), via misleading promises at kids sites, in poorly-disclosed bundles, and otherwise without appropriate notice and consent — so ads shown by 180 are presumptively unwanted. Meanwhile, my testing confirms that 180solutions tracks what web sites users visit — rightly earning the name “spyware” since 180 installations can be nonconsensual. 180 also attracts attention for its large installed base and substantial venture funding. Crucially, 180’s self-serve advertising sales system, MetricsDirect, lets anyone hire 180 to show a given ad URL when users visit URLs with a given keyword — without so much as speaking to a 180 representative. In combination, these factors make 180 among the worst offenders at showing problematic ads: Bad actors can use 180 to show advertisers’ sites to millions of users, without meaningful scrutiny by 180 and, thanks to ad intermediaries’ tracking systems, sometimes even without advertisers’ knowledge.

Earlier this month, I found that 180solutions tracks a total of 510,211 keywords within the URLs users visit. In my testing, 157,083 of these keywords are actively targeted with ads. A total of 88,388 distinct ads target these keywords. (As expected, many ads target more than one keyword. I measure “distinct ads” based on use of distinct ad URLs.)

Of these 88,388 ads, many pass through well-known intermediaries which serve to facilitate relationships between advertisers and 180; to track views, clicks, or purchases; and/or to track orcoordinate facilitate payment. The listing below gives a summary of the number of ads (of these 88,388) found to be actively loading content from the specified intermediaries. The listing reports only intermediaries associated with 500 or more different 180solutions ads.

| Advertising intermediary |

# ads

|

| Traditional banner ad networks / tracking services |

| Atlas DMT (aQuantive) (NASDAQ: AQNT) |

2,666

|

| Adteractive |

2,231

|

| DoubleClick (NASDAQ: DCLK) |

1,352

|

| FastClick (NASDAQ: FSTC) |

513

|

| Affiliate networks |

| ClickBank |

1,054

|

| Commission Junction (including BeFree) (ValueClick) (NASDAQ: VCLK) |

686

|

| Syndicated search engine advertising |

| Google (NASDAQ: GOOG) |

4,678

|

See disclosure as to Advertising.com (AOL).

Update: I’ve been asked for details about the “actively loading content from” criteria that governs inclusion in the table above. My scripts check for content loaded from an intermediary by looking for redirects, for loading an intermediary’s content in a FRAME or IFRAME, or for use of JavaScript to load arbitrary code from an intermediary. Most of the listed intermediaries primarily use the redirects and FRAME/IFRAME methods. But Google AdSense sites typically use JavaScript to load Google’s inline ads in a JavaScript-created subwindow. What all these practices have in common is that they actually show substantial content from the ad intermediary — not merely (for example) a small text link to an affiliate network.

Do Ad Intermediaries Intend to Support 180?

Multiple advertising intermediaries (and some big advertisers) have recently written to me to tell me that they “can’t” track how ads are being shown using their networks and systems. They apparently consider it impossible to track all their ads — so they think they shouldn’t be blamed if they fail, i.e. if their ads are shown through software installed improperly on users’ PCs.

I emphatically disagree. The task is definitely doable. I know because I’ve already done it.

advertisers

money

viewers

viewers

ad intermediaries

(e.g. Commission Junction)

money

viewers

viewers

independent intermediaries

(e.g. Top3offers)

money

viewers

viewers

spyware

(e.g. 180solutions)Flow of Traffic and Payments

Ad intermediaries are correct that the design of spyware and similar systems makes their traditional enforcement procedures ineffective. Historically, if an ad intermediary noticed that some client or site was showing its ads in a way the intermediary didn’t like, the intermediary could simply cancel the corresponding entity’s contract and withhold payments to that entity or refuse future business from that entity.

180solutions’ design (and others like it) wreaks havoc on this simple enforcement model. Many of 180’s ads are placed by 180 advertisers, acting in their own names, in general without disclosing that the resulting traffic will be shown in 180solutions pop-ups. For example, Top3offers.com pays 180solutions to show Top3offers URLs when users visit certain keywords pertaining to online dating. Top3offers then sends such traffic to Yahoo Personals via a Commission Junction tracking link, ultimately receiving payments for leads or signups. Yahoo and CJ did not request that Top3offers take any such action — and if they search their advertiser databases for 180solutions, they won’t find a match, because the underlying account is in the name of Top3offers, not 180. And of course Top3offers is just one of hundreds — thousands? — of middle-men using similar methods. (See e.g. ten specific examples I posted in detail last year — complete with packet logs, videos, etc.)

So it’s insufficient for ad intermediaries to merely search their databases for the names of known wrongdoers. Rather, rigorous enforcement requires examining actions, not just names. Savvy intermediaries need an enforcement system that monitors ads at trouble spots like 180solutions, that flags suspect ads shown there, and that does not naively assume that bad actors will be truthful in their statements to ad intermediaries. Conveniently, that’s precisely how my ad-tracking robot works — that’s precisely how I generated the table above.

This CJ/Top3offers example is just one of many, and of course facts vary across types of ad intermediaries. Because affiliate networks like Commission Junction generally pay commissions only when users make purchases, they tend to be particularly indiscriminate as to who can place such links and earn such commissions — operating under the mistaken assumption that if a user made a purchase, the traffic must have been legitimate. (They ignore the risk that the ad was improperly shown to the user, without appropriate prior consent.) Indeed, despite CJ having ended its direct relationship with 180, 180’s advertisers (the “independent intermediaries” in the diagram above) continue to run CJ links — apparently in the expectation of continuing to receive payment, i.e. because CJ won’t catch them. If CJ can’t identify and block this traffic, then CJ still earns its commissions on such traffic — so paradoxically CJ still profits from the activities of 180 and its advertisers.

How Google Gets Involved

PPC advertisers

money

viewers

viewers

Google (AdWords)

money

viewers

viewers

AdSense sites

money

viewers

viewers

180solutions

Flow of Traffic and Payments via Google

Google’s relationship with 180 proceeds in the convoluted path shown at right. Pay-per-click advertisers pay Google to show their ads on Google’s AdSense partner sites. Some AdSense members then pay 180 to show the members’ sites via 180solutions popups, such that funding ultimately flows as shown at right: From pay-per-click advertiser to Google to AdSense member site to 180solutions. (Example.)

Google’s relationship with 180 merits special discussion for at least two reasons. First, where other intermediaries often withhold from making claims about the quality of the sites they track or serve, Google tells its advertisers that sites showing Google ads are “high-quality” and “reviewed and monitored according to … rigorous standards.” Furthermore, Google’s AdSense Program Policies provide that AdSense ads may not be displayed in pop-ups or via client software (like 180).

Second, notwithstanding Google’s statements about the quality of sites in its network, Google’s relationship with 180 is surprisingly large: Of the 88,388 current 180solutions ads, some 4,678 (5%+) include Google AdSense ads, making Google the most prevalent source of funding for web sites advertising with 180solutions (at least when measured by the methods set out above).

Despite the “quality” claims in Google’s statements to its advertisers, it is unclear what steps Google takes to enforce its stated rules. I sent an inquiry to Google staff two weeks ago, but I have not yet received a response.

That Google AdSense members promote their sites through pop-ups like 180’s is entirely foreseeable. Indeed, Google apparently foresaw this problem when it included AdSense policy text to specifically forbid this practice. Now that the problem is observed and now that it turns out to be substantial, will Google enforce its existing rule?

Update: In a blog entry responding to this piece, Eric Goldman concludes “nothing about traffic to AdSense sites sourced by adware vendors runs contrary to Google’s stated policies.” Perhaps I haven’t explained (what I view to be) the violation sufficiently clearly. So let me try again. First, AdSense Program Policies require that “No Google ad … may be displayed on any … pop-ups” — seemingly violated when 180 shows pop-ups of sites that include AdSense ads. Second, AdSense’s Terms and Conditions provide as follows (emphasis added):

“5. Prohibited Uses. You shall not, and shall not authorize or encourage any third party to … (vi) directly or indirectly access … Ads … through or from … any software application.

My example shows behavior that seems to exactly match the prohibited activity: An AdSense site hires 180 (surely “authoriz[ation]” and “encourage[ment]” within the meaning of the rule) to show the AdSense site, including showing (and thereby “access[ing]”) the site’s AdSense ads, as a result of the 180 software application observing the user viewing certain targeted sites. To me, the inconsistency between this practice and the stated rule seems abundantly clear.

Methodology, Enhancements, and Future Work

For those interested in my methodology: I’ve previously written about how to learn what ads 180 shows when users visit certain sites. The results above are derived from this list of ad URLs by processing with a robot that looks at the contents of each ad URL, attempting to determine and classify any ad networks or other intermediaries forwarding users to other advertising elsewhere.

Because my robots are imperfect, my methods tend to undercount the number of ads actually coming from each ad intermediary. My robots can track and analyze most standard HTML, including server-side redirects, client-side redirects, frames, iframes, and even basic JavaScript. But encoded JavaScript and certain other tricks currently serve to stop my robots from successfully and fully analyzing all ads.

In the coming weeks I’ll be posting more specific data — perhaps a listing of specific ads shown through unwanted software on users’ PCs, passing through some or all of the ad intermediaries listed above; perhaps videos and packets logs examining particular examples in detail. Interested readers should feel free to send suggestions and requests. Note that my March 2005 eXact Advertising testing reported the intermediaries associated with most of eXact’s current ads.

Where Do We Go From Here?

At a recent NAI Spyware conference, advertising executives reportedly discussed “creating robot-like technology to follow … advertisement[s].” They’re on the right track — but it’s unfortunate that they’re still just “discussing” rather than actively moving forward with the work. If I can do the analysis above — using just my ordinary cablemodem, some VB scripts running within Microsoft Access, and a single spare PC in my lab — then surely NAI’s members can do a lot better.

NAI members like aQuantive and DoubleClick are currently placing and tracking thousands of ads that are helping to fund the unwanted software plaguing users’ PCs. The time for talking has long since ended.

Disclosure: I serve as a consultant to AOL on certain matters related to spyware. If AOL’s Advertising.com ads had been sufficiently frequent to meet the criteria for inclusion in the table, I would have included them. However, in fact AOL / Advertising.com serve/track/support substantially less than 500 ads shown by 180solutions, therefore not calling for inclusion in the table. This calculation is based on 180solutions ads as they stood before I sent AOL any report as to its Advertising.com ads being shown by or through 180solutions. To the extent that AOL’s numbers are below those of other ad intermediaries, I attribute this to AOL’s March 2005 decision to stop doing business with all adware companies.