MegaLag’s December 2024 video introduced 18 million viewers to serious questions about Honey, the widely-used browser shopping plug-in—in particular, whether Honey abides by the rules set by affiliate networks and merchants, and whether Honey takes commissions that should flow to other affiliates. I wrote in January that I thought Honey was out of line. In particular, I pointed out the contracts that limit when and how Honey may present affiliate links, and I applied those contracts to the behavior MegaLag documented. Honey was plainly breaking the rules.

As it turns out, Honey’s misconduct is considerably worse than MegaLag, I, or others knew. When Honey is concerned that a user may be a tester—a “network quality” employee, a merchant’s affiliate manager, an affiliate, or an enthusiast—Honey designs its software to honor stand down in full. But when Honey feels confident that it’s being used by an ordinary user, Honey defies stand down rules. Multiple methods support these conclusions: I extracted source code from Honey’s browser plugin and studied it at length, plus I ran Honey through a packet sniffer to collect its config files, and I cross-checked all of this with actual app behavior. Details below. MegaLag tested too, and has a new video with his updated assessment.

(A note on our relationship: MegaLag figured out most of this, but asked me to check every bit from first principles, which I did. I added my own findings and methods, and cross-checked with VPT records of prior observations as well as historic Honey config files. More on that below, too.)

Behaving better when it thinks it’s being tested, Honey follows in Volkswagen’s “Dieselgate” footsteps. Like Volkswagen, the cover-up is arguably worse than the underlying conduct. Facing the allegations MegaLag presented last year, Honey could try to defend presenting its affiliate links willy-nilly—argue users want this, claim to be saving users money, suggest that network rules don’t apply or don’t mean what they say. But these new allegations are more difficult to defend. Designing its software to perform differently when under test, Honey reveals knowing what the rules require and knowing they’d be in trouble if caught. Hiding from testers reveals that Honey wanted to present affiliate links as widely as possible, despite the rules, so long as it doesn’t get caught. It’s not a good look. Affiliates, merchants, and networks should be furious.

What the rules require

The basic bargain of affiliate marketing is that a publisher presents a link to a user, who clicks, browses, and buys. If the user makes a purchase, commission flows to the publisher whose link was last clicked.

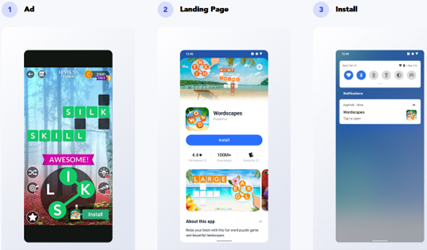

Shopping plugins and other client-side software undermine the basic bargain of affiliate marketing. If a publisher puts software on a user’s computer, that software can monitor where the user browses, present its affiliate link, and always (appear to) be “last”—even if it had minimal role in influencing the customer’s purchase decision.

Affiliate networks and merchants established rules to restore and preserve the bargain between what we might call “web affiliates” versus software affiliates. One, a user has to actually click a software affiliate’s link; decades ago, auto-clicks were common, but that’s long-since banned (yet nonetheless routine from “adware”-style browser plugins—example). Two, software must “stand down”—must not even show its link to users—when some prior web affiliate P has already referred a user to a given merchant. This reflects a balancing of interests: P wants a reasonable opportunity for the user to make a purchase, so P can get paid. If a shopping plugin could always present its offer, the shopping plugin would claim the commission that P had fairly earned. Meanwhile P wouldn’t get sufficient payment for its effort—and might switch to promoting some other merchant with rules P sees as more favorable. Merchants and networks need to maintain a balance in order to attract and retain web affiliates, which are understood to send traffic that’s substantially incremental (customers who wouldn’t have purchased anyway), whereas shopping plugins often take credit for nonincremental purchases. So if a merchant is unsure, it has good reason to err on the side of web affiliates.

All of this was known and understood literally decades ago. Stand-down rules were first established in 2002. Since then, they’ve been increasingly routine, and overall have become clearer and better enforced. Crucially, merchants and networks include stand-down rules in their contracts, making this not just a principle and a norm, but a binding contractual obligation.

Detecting testers

How can Honey tell when a user may be a tester? Honey’s code and config files show that they’re using four criteria:

- New accounts. If an account is less than 30 days old, Honey concludes the user might be a tester, so it disables its prohibited behavior.

- Low earnings-to-date. In general, under Honey’s current rules, if an account has less than 65,000 points of Honey earning, Honey concludes the user might be a tester, so it disables its prohibited behavior. Since 1,000 points can be redeemed for $10 of gift cards, this threshold requires having earned $650 worth of points. That sounds like a high requirement, and it is. But it’s actually relatively new: As of June 2022, there was no points requirement for most merchants, and for merchants in Rakuten Advertising, the requirement was just 501 points (about $5 of points). (Details below.)

- Honey periodically checks a server-side blacklist. The server can condition its decision on any factor known to the server, including the user’s Honey ID and cookie, or IP address inside a geofence or on a ban list. Suppose the user has submitted prior complaints about Honey, as professional testers frequently do. Honey can blacklist the user ID, cookie, and IP or IP range. Then any further requests from that user, cookie, or IP will be treated as high-risk, and Honey disables its prohibited behavior.

- Affiliate industry cookies. Honey checks whether a user has cookies indicating having logged into key affiliate industry tools, including the CJ, Rakuten Advertising, and Awin dashboards. If the user has such a cookie, the user is particularly likely to be a tester, so Honey disables its prohibited behavior.

If even one of these factors indicates a user is high-risk, Honey honors stand-down. But if all four pass, then Honey ignores stand-down rules and presents its affiliate links regardless of a prior web publisher’s role and regardless of stand-down rules. This isn’t a probabilistic or uncertain dishonoring of stand-down (as plaintiffs posited in litigation against Honey). Rather, Honey’s actions are deterministic: If a high-risk factor hits, Honey will completely and in every instance honor stand-down; and if no such factor hits, then Honey will completely and in every instance dishonor stand-down (meaning, present its link despite networks’ rules).

These criteria indicate Honey’s attempt to obstruct and frankly frustrate testers. In my experience from two decades of testing affiliate misconduct, it is routine for a tester to install a new shopping plugin on a new PC, create a new account, and check for immediate wrongdoing. By always standing down on new accounts (<30 days), Honey prevents this common test scenario from catching its stand-down violations. Of course diligent testers will check way past 30 days, but a tester on a short-term contract will perceive nothing amiss. Some clients may not pay for testers to stick with the task. And a client for some reason needing an immediate finding—perhaps to dispute Honey’s recent earnings—can’t get it.

The requirement of achieving sufficiently many points similarly stymies many testers. Over the years, a handful of my clients granted a budget for test purchases. But most did not. If I wanted to perform test purchases, I would have needed to spend my own money. Meanwhile, there’s no proper reason why a shopping app should stand down differently for users with points versus new users, so if testers assumed good faith by Honey, they’d have no reason to build up a points history. This criteria certainly prevented testers from uncovering what Honey was doing.

The interaction of account age, points history, and blacklist further stymies testing. Once a tester reports a specific observation of misconduct, Honey can blacklist the tester’s account—which will still do most things normally, but will begin to stand down even though unbanned accounts don’t stand down in the same circumstances. A tester who suspected this, would have to create a new account, wait 30 days, and build up a sizable points balance to see what Honey is actually doing for other users. That’s a genuine barrier, impeding even a tester who correctly proposes this hypothesis.

Honey’s detection of affiliate industry cookies is particularly revealing and, in my view, devastatingly incriminating. Maybe Honey could concoct a story about why it stands down less for established accounts and for high-points-earners. It would be a tall tale, but maybe Honey could convince some people. In contrast, it is inconceivable why a shopping plugin should care whether a user previously logged into an affiliate dashboard. There’s only one reason to check: to hide from testers. But that reveals Honey’s intent and Honey’s knowledge that its conduct is prohibited.

Evidence from hands-on testing

Multiple forms of evidence support my finding of Honey detecting testers. First, consider hands-on testing. With a standard test account with few or no points, Honey honored stand-down. See video 1. But when I tricked the Honey plugin into thinking I had tens of thousands of points (details below about how I did this), Honey popped up despite stand-down rules. See video 2. I repeated this test over multiple days, as to multiple merchants. The finding was the same every time. The only thing I changed between the “video 1” tests and “video 2” tests was the number of points supposedly associated with my account.

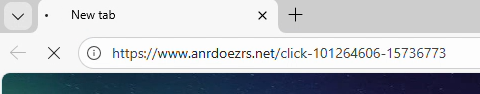

To demonstrate Honey checking for affiliate industry cookies, I added a step to my test scenario. With Honey tricked into thinking I had ample points, same as video 2, I began a test run by logging into a CJ portal used by affiliates. In all other respects, my test run was the same as video 2. Seeing the CJ portal cookie, Honey stood down. See video 3.

Evidence from technical analysis

Some might ask whether the findings in the prior section could be coincidence. Maybe Honey just happened to open in some scenarios and not others. Maybe I’m ascribing intentionality to acts that are just coincidence. Let me offer two responses to this hypothesis. One, my findings are repeatable, countering any claim of coincidence. Second, separate from hands-on testing, three separate types of technical analysis—config files, telemetry, and source code—all confirm the accuracy of the prior section.

Evidence from configuration files

Honey retrieves its configuration settings from JSON files on a Honey server. Honey’s core stand-down configuration is in standdown-rules.json, while the selective stand-down—declining to stand down according to the criteria described above—is in the separate config file ssd.json. Here’s the contents of ssd.json as of October 22, 2025, with // comments added by me

{"ssd": {

"base": {

"gca": 1, //enable affiliate console cookie check

"bl": 1, //enable blacklist check

"uP": 65000, //min points to disable standdown

"adb": 26298469858850

},

"affiliates": ["https://www.cj.com", "https://www.linkshare", "https://www.rakuten.com", "https://ui.awin.com", "https://www.swagbucks.com"], //affiliate console cookie domains to check

"LS": { //override points threshold for LinkShare merchants

"uP": 5001

},

"PAYPAL": {

"uL": 1,

"uP": 5000001,

"adb": 26298469858850

}

},

"ex": { //ssd exceptions

"7555272277853494990": { //TJ Maxx

"uP": 5001

},

"7394089402903213168": { //booking.com

"uL": 1,

"adb": 120000,

"uP": 1001

},

"243862338372998182": { //kayosports

"uL": 0,

"uP": 100000

},

"314435911263430900": {

"adb": 26298469858850

},

"315283433846717691": {

"adb": 26298469858850

},

"GA": ["CONTID", "s_vi", "_ga", "networkGroup", "_gid"] //which cookies to check on affiliate console cookie domains

}

}

On its own, the ssd config file is not a model of clarity. But source code (discussed below) reveals the meaning of abbreviations in ssd. uP (yellow) refers to user points—the minimum number of points a user must have in order for Honey to dishonor stand-down. Note the current base (default) requirement of uP user points at least 65,000 (green), though the subsequent section LS sets a lower threshold of just 5001 for merchants on the Rakuten Advertising (LinkShare) network. bl set to 1 instructs the Honey plugin to stand down if the server-side blacklist so instructs.

Meanwhile, the affiliates and ex GA data structures (blue), establish the affiliate industry cookie checks mentioned above. The “affiliates” entry lists domain where cookies are to be checked. The ex GA data structure lists which cookie is to be checked for each domain. Though these are presented as two one-dimensional lists, Honey’s code actually checks them in conjunction – checks the first-listed affiliate network domain for the first-listed cookie, then the second, and so forth. One might ask why Honey stored the domain names and cookie names in two separate one-dimensional lists, rather than in a two-dimensional list, name-value pair, or similar. The obvious answer is that Honey’s approach kept the domain names more distant from the cookies on those domains, making its actions that much harder for testers to notice even if they got as far as this config file.

The rest of ex (red) sets exceptions to the standard (“base”) ssd. This lists five specific ecommerce sites (each referenced with an 18-digit ID number previously assigned by Honey) with adjusted ssd settings. For Booking.com and Kayosports, the ssd exceptions set even higher points requirements to cancel standdown (120,000 and 100,000 points, respectively), which I interpret as response to complaints from those sites.

Evidence from telemetry

Honey’s telemetry is delightfully verbose and, frankly, easy to understand, including English explanations of what data is being collected and why. Perhaps Google demanded improvements as part of approving Honey’s submission to Chrome Web Store. (Google enforces what it calls “strict guidelines” for collecting user data. Rule 12: data collection must be “necessary for a user-facing feature.” The English explanations are most consistent with seeking to show Google that Honey’s data collection is proper and arguably necessary.) Meanwhile, Honey submitted much the same code to Apple as an iPhone app, and Apple is known to be quite strict in its app review. Whatever the reason, Honey telemetry reveals some important aspects of what it is doing and why.

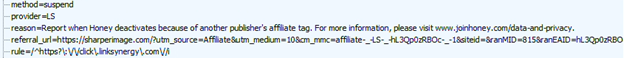

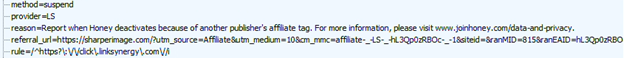

When a user with few points gets a stand-down, Honey reports that in telemetry with the JSON data structure “method”:”suspend”. Meanwhile, the nearby JSON variable state gives the specific ssd requirement that the user didn’t satisfy—in my video 1: “state”:”uP:5001” reporting that, in this test run, my Honey app had less than 5001 points, and the ssd logic therefore decided to stand down. See video 1 at 0:37-0:41, or screenshots below for convenience. (My network tracing tool converted the telemetry from plaintext to a JSON tree for readability.)

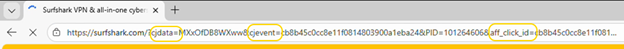

When I gave myself more points (video 2), state instead reported ssd—indicating that all ssd criteria were satisfied, and Honey presented its offer and did not stand down. See video 2 at 0:32.

Finally, when I browsed an affiliate network console and allowed its cookie to be placed on my PC, Honey telemetry reported “state”:“gca”. Like video 1, the state value reports that ssd criteria were not satisfied, in this case because the gca (affiliate dashboard cookie) requirement was triggered, causing ssd to decide to stand down. See video 3 at 1:04-1:14.

In each instance, the telemetry matched identifiers from the config file (ssd, uP, gca). And as I changed from one test run to another, the telemetry transmissions tracked my understanding of Honey’s operation. Readers can check this in my videos: After Honey does or doesn’t stand down, I opened Fiddler to show what Honey reported in telemetry, in each instance in one continuous video take.

Evidence from code

As a browser extension, Honey provides client-side code in JavaScript. Google’s Code Readability Requirements allow minification—removing whitespace, shortening variable and function names. Honey’s code is substantial—after deminification, more than 1.5 million lines. But a diligent analyst can still find what’s relevant. In fact the relevant parts are clustered together, and easily found via searches for obvious string such as “ssd”.

In a surprising twist, Honey in one instance released something approaching original code to Apple as an iPhone app. In particular, Honey included sourceMappingURL metadata that allows an analyst to recover original function names and variable names. (Instructions.) That release was from a moment in time, and Honey subsequently made revisions. But where that code is substantially the same as the code currently in use, I present the unobfuscated version for readers’ convenience. Here’s how it works:

First, there’s setup, including periodically checking the Honey killswitch URL /ck/alive:

return e.next = 7, fetch("".concat("https://s.joinhoney.com", "/ck/alive"));

If the killswitch returns “alive”, Honey sets the bl value to 0:

c = S().then((function(e) {

e && "alive" === e.is && (o.bl = 0)

}))

The ssd logic later checks this variable bl, among others, to decide whether to cancel standdown.

The core ssd logic is in a long function called R() which runs an infinite loop with a switch syntax to proceed through a series of numbered cases.

function(e) {

for (;;) switch (e.prev = e.next) {

Focusing on the sections relevant to the behavior described above: Honey makes sure the user’s email address doesn’t include the string “test”, and checks whether the user is on the killswitch blacklist.

if (r.email && r.email.match("test") && (o.bl = 0), !r.isLoggedIn || t) {

e.next = 7;

break

Honey computes the age of the user’s account by subtracting the account creation date (r.created) from the current time:

case 8:

o.uL = r.isLoggedIn ? 1 : 0, o.uA = Date.now() - r.created;

Honey checks for the most recent time a resource was blocked by an ad blocker:

case 20:

return p = e.sent, l && a.A.getAdbTab(l) ? o.adb = a.A.getAdbTab(l) : a.A.getState().resourceLastBlockedAt > 0 ? o.adb = a.A.getState().resourceLastBlockedAt : o.adb = 0

Honey checks whether any of the affiliate domains listed in the ssd affiliates data structure has the console cookie named in the GA data structure.

m = p.ex && p.ex.GA || []

g = i().map(p.ssd && p.ssd.affiliates, (function(e) {

return f += 1, u.A.get({

name: m[f], //cookie name from GA array

url: e //domain to be checked

}).then((function(e) {

e && (o.gca = 0) //if cookie found, set gca to 0

}))

Then the comparison function P() compares each retrieved or calculated value to the threshold from ssd.json. The fundamental logic is that if any retrieved or calculated value (received in variable e below) is less than the threshold t from ssd, the ssd logic will honor standdown. In contrast, if all four values exceed the threshold, ssd will cancel the standdown. If this function elects to honor standdown, the return value gives the name of the rule (a) and the threshold (s) that caused the decision (yellow highlighting). If this function elects to dishonor standdown, it returns “ssd” (red) (which is the function’s default if not overridden by the logic that folllows). This yields the state= values I showed in telemetry and presented in screenshots and videos above.

function P(e, t) {

var r = "ssd";

return Object.entries(t).forEach((function(t) {

var n, o, i = (o = 2, _(n = t) || b(n, o) || y(n, o) || g()),

a = i[0], // field name (e.g., uP, gca, adb)

s = i[1]; // threshold value from ssd.json

"adb" === a && (s = s > Date.now() ? s : Date.now() - s), // special handling for adb timestamps

void 0 !== e[a] && e[a] < s && (r = "".concat(a, ":").concat(s))

})), r

}

Special treatment of eBay

Reviewing both config files and code, I was intrigued to see eBay called out for greater protections than others. Where Honey stands down for other merchant and networks for 3,600 seconds (one hour), eBay gets 86,400 seconds (24 hours).

"regex": "^https?\\:\\/\\/rover\\.ebay((?![\\?\\&]pub=5575133559).)*$",

"provider": "LS",

"overrideBl": true,

"ttl": 86400

Furthermore, Honey’s code includes an additional eBay backstop. No matter what any config file might stay, Honey’s ssd selective stand-down logic will always stand down on ebay.com, even if standard ssd logic and config files would otherwise decide to disable stand-down. See this hard-coded eBay stand-down code:

...

const r = e.determineSsdState ? await e.determineSsdState(_.provider, v.id, i).catch() : null,

a = "ssd" === r && !/ebay/.test(p);

...

Why such favorable treatment of eBay? Affiliate experts may remember the 2008 litigation in which eBay and the United States brought civil and criminal charges against Brian Dunning and Shawn Hogan, who were previously eBay’s two largest affiliates—jointly paid more than $20 million in just 18 months. I was proud to have caught them—a fact I can only reveal because an FBI agent’s declaration credited me. After putting its two largest affiliates in jail and demanding repayment of all the money they hadn’t spent or lost, eBay got a well-deserved reputation for being smart and tough at affiliate compliance. Honey is right to want to stay on eBay’s good side. At the same time, it’s glaring to see Honey treat eBay so much better than other merchants and networks. Large merchants on other networks could look at this and ask: If eBay get a 24 hour stand-down and a hard-coded ssd exception, why are they treated worse?

Change over time

I mentioned above that I have historic config files. First, VPT (the affiliate marketing compliance company where I am Chief Scientist) preserved a ssd.json from June 2022. As of that date, Honey ssd had no points requirement for most networks. See yellow “base” below, notably in this version including a uP section. For LinkShare (Rakuten Advertising), the June 2022 ssd file required 501 points (green), equal to about $5 of earning to date.

{"ssd": {

"base": {"gca": 1, "bl": 1},

"affiliates": ["https://www.cj.com", "https://www.linkshare", "https://www.rakuten.com", "https://ui.awin.com", "https://www.swagbucks.com"],

"LS": {"uL": 1, "uA": 2592000, "uP": 501, "SF": {"uP": 200} }, ...

In April 2023, Archive.org preserved ssd.json, with the same settings.

Notice the changes from 2022-2023 to the present—most notably, a huge increase in points required for Honey to not stand-down. The obvious explanation for the change is MegaLag’s December 2024 video, and resulting litigation, which brought new scrutiny to whether Honey honors stand-down.

A second relevant change is that, as of 2022-2023, the ssd.json included a uA setting for LinkShare, requiring an account age of at least 2,592,000 seconds (30 days). But the current version of ssd.json has no uA setting, not for LinkShare merchants nor for any other merchants. Perhaps Honey thinks the high points requirement (65,000) now obviates the need for a 30-day account age.

In litigation, plaintiffs should be able to obtain copies of Honey config files indicating when the points requirement increased, and for that matter management discussions about whether and why to make this change. If the config files show ssd in similar configuration from 2022 through to fall 2024, but cutoffs increased shortly after MegaLag’s video, it will be easy to infer that Honey reduced ssd, and increased standdown, after getting caught.

Despite Honey’s recently narrowing ssd to more often honor stand-down, this still isn’t what the rules require. Rather than comply in full, Honey continued not to comply for the highest-spending users, those with >65k points—who Honey seems to figure must be genuine users, not testers or industry insiders.

Tensions between Honey and LinkShare (Rakuten Advertising)

Honey’s LinkShare exception presents a puzzle. In 2022 and 2023, Honey was stricter for LinkShare merchants—more often honoring stand-down, and dishonoring stand-down only for users with at least 501 points. But in the current configuration, Honey applies a looser standard for LinkShare merchants: Honey now dishonors LinkShare stand-down once a user has 5,001 points, compared to the much higher 65,000-point requirement for merchants on other networks. What explains this reversal? Honey previously wanted to be extra careful for LinkShare merchants—so why now be less careful?

The best interpretation is a two-step sequence. First, at some point Honey raised the LinkShare threshold from 501 to 5,001 points—likely in response to a merchant complaint or LinkShare network quality concerns. Second, when placing that LinkShare-specific override into ssd.json, Honey staff didn’t consider how it would interact with later global rules—especially since the overall points requirement (base uA) didn’t yet exist. Later, MegaLag’s video pushed Honey to impose a 65,000-point threshold for dishonoring stand-down across all merchants—and when Honey staff imposed that new rule, they overlooked the lingering LinkShare override. A rule intended to be stricter for LinkShare now inadvertently makes LinkShare more permissive.

Reflections on hiding from testers

In a broad sense, the closest analogue to Honey’s tactics is Volkswagen Dieselgate Recall the 2015 discovery that Volkswagen programmed certain diesel engines to activate their emission controls only during laboratory testing, but not in real-world driving. Revelation of Volkswagen’s misconduct led to the resignation of Volkswagen’s CEO. Fines, penalties, settlements, and buyback costs exceeded $33 billion.

In affiliate marketing, numbers are smaller, but defeating testing is, regrettably, more common. For decades I’ve been tracking cookie-stuffers, which routinely use tiny web elements (1×1 IFRAMEs and IMG tags) to load affiliate cookies, and sometimes further conceal those elements using CSS such as visibility:none. Invisibility quite literally conceals what occurs. In parallel, affiliates also deployed additional concealment methods. Above, I mentioned Dunning and Hogan, who concealed their miscondudct in two additional ways. First, they stuffed each IP address at most once. Consider a researcher who suspected a problem, but didn’t catch it the first time. (Perhaps the screen-recorder and packet sniffer weren’t running. Or maybe this happened on a tester’s personal machine, not a dedicated test device.) With a once-per-IP-address rule, the researcher couldn’t easily get the problem to recur. (Source: eBay complaint, paragraph 27: “… only on those computers that had not been previously stuffed…”) Second, they geofenced eBay and CJ headquarters. (Source.) Shawn Hogan even admitted intentionally not targeting the geographic areas where he thought I might go. Honey’s use of a server-side blacklist allows similar IP filtering and geofencing, as well as more targeted filtering such as always standing down for the specific IPs, cookies, and accounts that previously submitted complaints.

A 2010 blog from affiliate trademark testers BrandVerity uncovered an anti-test strategy arguably even closer to what Honey is doing. In this period, history sniffing vulnerabilities let web sites see what other pages a user had visited: Set visited versus unvisited links to different colors, link to a variety of pages, and check the color of each link. BV’s perpetrator used this tactic to see whether a user had visited tools used by affiliate compliance staff (BV’s own login page, LinkShare’s dashboard and internal corporate email, and ad-buying dashboards for Google and Microsoft search ads). If a user had visited any of these tools, the perpetrator would not invoke its affiliate link—thereby avoiding revealing its prohibited behavior (trademark bidding) to users who were plainly affiliate marketing professionals. For other users, the affiliate bid on prohibited trademark terms and invoked affiliate links. Like Honey, this affiliate distinguished normal users from industry insiders based on prior URL visits. Of course Honey’s superior position, as a browser plugin, lets it directly read cookies without resorting to CSS history. But that only makes Honey worse. No one defended the affiliate BV caught, and I can’t envision anyone defending Honey’s tactic here.

In a slightly different world, it might be considered part of the rough-and-tumble world of commerce that Honey sometimes takes credit for referrals that others think should accrue to them. (In fact, that’s an argument Honey recently made in litigation: “any harm [plaintiffs] may have experienced is traceable not to Honey but to the industry standard ‘last-click’ attribution rules.”) There, Honey squarely ignores network rules, which require Honey to stand down although MegaLag showed Honey does not. But if Honey just ignored network stand-down rules, brazenly, it could push the narrative that networks and merchants agreed since, admittedly, they didn’t stop Honey. By hiding, Honey instead reveals that they know their conduct is prohibited. When we see networks and merchants that didn’t ban Honey, the best interpretation (in light of Honey’s trickery) is not that they approved of Honey’s tactics, but rather that Honey’s concealment prevented them from figuring out what Honey was doing. And the effort Honey expended, to conceal its behavior from industry insiders, makes it particularly clear that Honey knew it would be in trouble if it was caught. Honey’s knowledge of misconduct is precisely opposite to its media response to MegaLag’s video, and equally opposite to its position in litigation.

Five years ago Amazon warned shoppers that Honey was a “security risk.” At the time, I wrote this off as sour grapes—a business dispute between two goliaths. I agreed with Amazon’s bottom line that Honey was up to no good, but I thought the real problems with Honey were harm to other affiliates and harm to merchants’ marketing programs, not harms to security. With the passage of time, and revelation of Honey’s tactics including checking other companies’ cookies and hiding from testers, Amazon is vindicated. Notice Honey’s excessive permission—which includes letting Honey read users’ cookies at all sites. That’s well beyond what a shopping assistant truly needs, and it allows all manner of misconduct including, unfortunately, what I explain above. Security risk, indeed. Kudos to Amazon for getting this right from the outset.

At VPT, the ad-fraud consultancy, we monitor shopping plugins for abusive behavior. We hope shopping plugins will behave forthrightly—doing the same thing in our test lab that they do for users. But we don’t assume it, and we have multiple strategies to circumvent the techniques that bad actors use to trick those monitoring their methods. We constantly iterate on these approaches as we find new ways of concealment. And when we catch a shopping plugin hiding from us, we alert our clients not just to their misconduct but also to their concealment—an affirmative indication that this plugin can’t be trusted. We have scores of historic test runs showing misconduct by Honey in a variety of configurations, targeting dozens of merchants on all the big networks, including both low points and high points, with both screen-cap video and packet log evidence of Honey’s actions. We’re proud that we’ve been testing Honey’s misconduct for years.

What comes next

I’m looking forward to Honey’s response. Can Honey leaders offer a proper reason why their product behaves differently when under test, versus when used by normal users? I’m all ears.

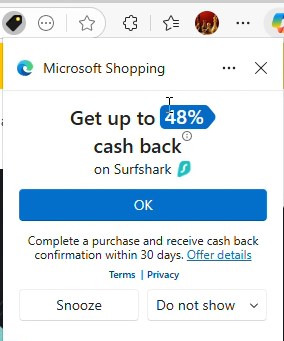

Honey should expect skepticism from Google, operator of the Chrome Web Store. Google is likely to take a dim view of a Chrome plugin hiding from testers. Chrome Web Store requires “developer transparency” and specifically bans “dishonest behavior.” Consider also Google’s prohibition on “conceal[ing] functionality”. Here, Honey was hiding not from Google staff but from merchants and networks, but this still violates the plain language of Google’s policy as written.

Honey also distributes its Safari extension through the Apple App Store, requiring compliance with Apple Developer Program policies. Apple’s extension policies are less developed, yet Apple’s broader app review process is notoriously strict. Meanwhile Apple operates an affiliate marketing program, making it particularly natural for Apple to step into the shoes of merchants who were tricked by Honey’s concealment. I expect a tough sanction from Apple too.

Meanwhile, class action litigation is ongoing on behalf of publishers who lose marketing commissions when Honey didn’t stand down. Nothing in the docket indicates that Plaintiff’s counsel know the depths of Honey’s efforts to conceal its stand-down violations. With evidence that Honey was intentionally hiding from testers, Plaintiffs should be able to strengthen their allegations of both the underlying misconduct and Honey’s knowledge of wrongdoing. My analysis also promises to simplify other factual aspects of the litigation. The consolidated class action complaint discusses unpredictability of Honey’s standdown but doesn’t identify the factors that make Honey seem unpredictable—by all indications because plaintiffs (quite understandably) don’t know. Faced with unpredictability, plaintiffs resorted to monte carlo simulation to analyze the probability that Honey harmed a given publisher in a series of affiliate referrals. But with clarity on what’s really going on, there’s no need for statistical analysis, and the case gets correspondingly simpler. The court recently instructed plaintiffs to amend their complaint, and surely counsel will emphasize Honey’s concealment in their next filing.

See also my narrated explainer video.

Notes on hands-on testing methods

Hands-on testing of the relevant scenarios presented immediate challenges. Most obviously, I needed to test what Honey would do if it had tens of thousands of points, valued at hundreds of dollars. But I didn’t want to make hundreds or thousands of dollars of test purchases through Honey.

To change the Honey client’s understanding of my points earned to date, I used Fiddler, a standard network forensics tool. I wrote a few lines of FiddlerScript to intercept messages between the Honey plug-in and the Honey server to report that I had however many points I wanted for a given test. Here’s my code, in case others want to test themselves:

//buffer responses for communications to/from joinhoney.com

//buffer allows response revisions by Fiddler

static function OnBeforeRequest(oSession: Session) {

if (oSession.fullUrl.Contains("joinhoney.com")) {

oSession.bBufferResponse = true;

}

}

//rewrite Honey points response to indicate high values

static function OnBeforeResponse(oSession: Session) {

if (oSession.HostnameIs("d.joinhoney.com") && oSession.PathAndQuery.Contains("ext_getUserPoints")){

s = '{"data":{"getUsersPointsByUserId":{"pointsPendingDeposit":67667,"pointsAvailable":98765,"pointsPendingWithdrawal":11111,"pointsRedeemed":22222}}}';

oSession.utilSetResponseBody(s);

}

}

This fall, VPT added this method, and variants of it, to our automated monitoring of shopping plugins.

Update (January 6, 2025): VPT announced today that it has 401 videos on file showing Honey stand-down violations as to 119 merchants on a dozen-plus networks.