Beginning in 2005, I flagged serious problems with IAC/Ask.com toolbars — including installations through security exploits and through bundles that nowhere sought user consent, installations targeting kids, rearranging users’ browsers to invite unintended searches, and showing a veritable onslaught of ads. IAC’s practices have changed in various respects, but the core remains as I previously described it: IAC’s search advertising business exists not to solve a genuine user need or provide users with genuine assistance, but to prey on users who — through inattention, inexperience, youth, or naivete — stumble into IAC’s properties.

Crucially, IAC remains substantially dependent on Google for monetization of IAC’s search services. A rigorous application of Google’s existing rules would put a stop to many of IAC’s practices, and sensible updated rules — following the stated objective of Google’s existing policies — would end much of the rest.

In this piece I examine current IAC toolbar installation practices (including targeting kids and soliciting installations when users are attempting to install security updates), the effects of IAC toolbars once installed (including excessive advertising and incomplete uninstall), and IAC’s search arbitrage business. I conclude by flagging advertisements with impermissibly large clickable areas (for both toolbars and search arbitrage), and I call on Google to put an end to Ask’s practices.

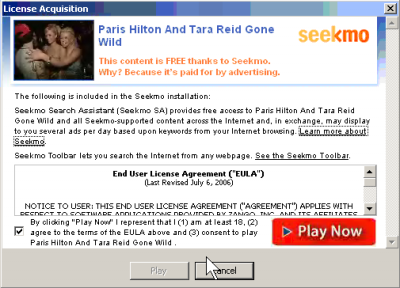

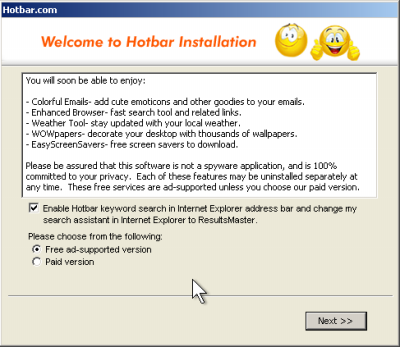

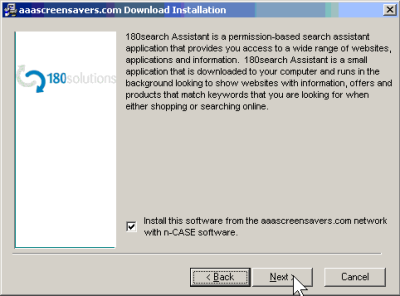

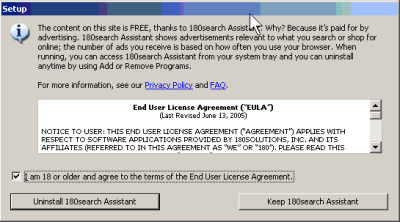

IAC’s search toolbar business is grounded in placing IAC toolbars on as many computers as possible. To that end, IAC offers 50+ different toolbars with a variety of branding — Webfetti (“free Facebook graphics”), Guffins (“virtual pet games”), religious toolbars of multiple forms (Know the Bible, Daily Bible Guide, Daily Jewish Guide), screensavers, games, and more. One might reasonably ask: Why would a user want such a toolbar?

IAC ad promises “free online television” but actually merely links to material already on the web; promises an “app” but actually provides a search toolbar.

IAC ad promises “free online television” but actually merely links to material already on the web; promises an “app” but actually provides a search toolbar.

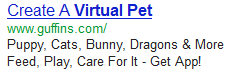

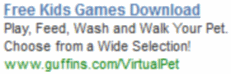

IAC ad solicits installations via “virtual pet” ad distinctively catering to kids.

IAC ad solicits installations via “virtual pet” ad distinctively catering to kids.

Other IAC Guffins ads specifically invite “kids” to install. (Screenshot by iSpionage)

Other IAC Guffins ads specifically invite “kids” to install. (Screenshot by iSpionage)

IAC Guffins offer features multiple animated cartoon images, distinctively catering to kids.

The Television Fanatic toolbar is instructive. IAC promotes this toolbar with search ads that promise “free online television” and “turn your computer into a TV watch full TV episode w free app.” It sounds like an attractive deal — many users would relish the ability to watch free live broadcast television on an ordinary computer, and it would not be surprising if such a service required downloading some sort of desktop application or browser plug-in. But in fact Television Fanatic offers nothing of the sort. To the extent that Television Fanatic offers the “free online television” promised in the ad, it only links to ordinary video content already provided by others. (For example, I clicked the toolbar’s “ABC” link and was taken to http://abc.go.com/watch/ — an ordinary ABC link equally available to users without Television Fanatic. That’s a far cry from IAC’s promise of special access to premium material.

Meanwhile, IAC’s Guffins toolbar distinctively targets kids. IAC promotes Guffins via search ads for terms like “virtual pet”, and the resulting ad says Guffins offers “puppy, cats, bunny, dragons & more” which a user can “feed, play, [and] care for.” The landing page features four animated animals with oversized faces and overstated features, distinctively attractive to children. Under COPPA factors or any intuitive analysis, IAC clearly targets kids. Indeed, ad tracking service iSpionage reports Guffins ads touting “Free Kids Games Download”, “Free Kids Computer Games”, “Play Kids Games Online”, and more — explicitly inviting children to install Guffins. Of course kids are ill-equipped to evaluate IAC’s offer — less likely to notice IAC’s disclosures of an included toolbar, less likely to understand what a search toolbar even is, and less able to evaluate the wisdom of installing such a toolbar in exchange for games.

While IAC’s ads often promise an “app” (including as shown in the ad screenshots at right), IAC actually offers just toolbars — add-ins appearing within web browsers, not the freestanding applications that the ads suggest. That’s all the more deceptive: IAC enticed users with the promise of genuine distinct programs offering exceptional video content and rich gaming. Instead IAC provided browser plug-ins that claim valuable screen space whenever users browse the web. And far from providing exclusive content, IAC toolbars send users to material already on the web and driving traffic to IAC’s advertising displays (as detailed in the next section). That’s strikingly inferior.

IAC’s toolbar installation practices stack up unfavorably vis-a-vis applicable Google policies, industry standards, and regulatory requirements. Google’s Software Principles call for “Upfront disclosure” with no suggestion that an app may promise one thing in an initial solicitation, then something else in a subsequent landing page. (IAC is obliged to comply with Google’s rules because IAC toolbars show ads from Google, as discussed in the next section.) Meanwhile, the Anti-Spyware Coalition specifically flags installations targeting children, allowing bundling by affiliates, and modifying browser settings as risk factors making software a greater concern. Even decades-old FTC rules are on point, disallowing “deceptive door openers” that promise one thing at the outset (like IAC’s initial promise of “free online television”) but later deliver something importantly different (a search toolbar).

Web searches reveal numerous user complaints about IAC toolbars. Consider search results for “televisionfanatic”. A first result links to product’s official site. Second is a Sitejabber forum with 20 harsh reviews. (17 reviewers gave Television Fanatic just one star out of five, with comments systematically reporting surprise and annoyance at the toolbar’s presence.) The third result advises “How to uninstall a Television fanatic toolbar”, and the fourth is multiple Yahoo Answers discussions including a user asking “Is television fanatic toolbar a virus?” and others repeatedly complaining about unintended installation. Clearly numerous users are dissatisfied with Television Fanatic.

So too for DailyBibleGuide. In a Q1 2011 earnings call, IAC CEO Greg Blatt touted the DailyBibleGuide toolbar as a new product IAC is particularly proud of. But a Google search results for “DailyBibleGuide” include a page advising “do not download Dailybiblestudy, Dailybibleguide, or Knowthebible extension.” There and elsewhere, users seem surprised to receive IAC’s toolbars. Reading users’ complaints, it seems their confusion ultimately results from IAC’s decision to deliver bible trivia via a toolbar. After all, such material would more naturally be delivered via a web page, email newsletter, or perhaps RSS feed. IAC chose the odd strategy of toolbar-based delivery not because it was genuinely what users wanted, but because this is the format IAC can best monetize. No wonder users systematically end up disappointed.

By all indications, a huge number of users are running IAC toolbars. The IAC toolbars discussed in this section all send users to mywebsearch.com, a site users are unlikely to visit except if sent there by an IAC toolbar. Alexa reports that mywebsearch.com is the #41 most popular site in the US and #71 worldwide — more popular than Instagram, Flickr, Pandora, and Hulu.

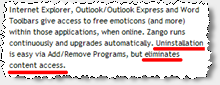

Some of IAC’s browser configuration changes remain in place even if a user removes an IAC toolbar. I installed then uninstalled an IAC Television Fanatic toolbar and received a prompt instructing “Click here for help on resetting your home page and default search settings.” The resulting page specified four different procedures totaling 16 steps — far more lengthy than the initial installation. I can see no proper reason why uninstall is so difficult. Indeed, IAC’s incomplete uninstall specifically violates Google’s October 2012 requirement that “During the uninstall process, users must be presented with a choice that gives them the option of returning their browser’s user settings to the previous settings.” Google’s Software Principles are also on point, instructing that uninstall must be “easy” and must disable “all functions of the application” — whereas IAC’s automated installer does not undo all of IAC’s changes, and IAC’s manual 16-step process is the opposite of “easy.”

The Special Problems of IAC Ask Toolbar Installed by Oracle’s Java Updates

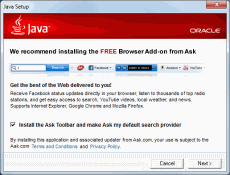

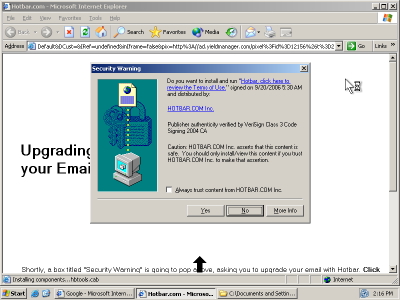

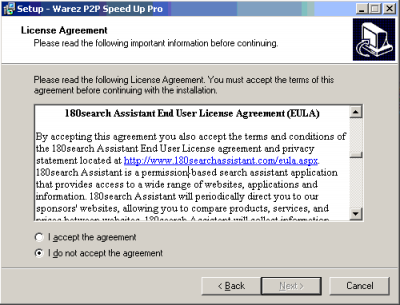

Ongoing Oracle Java updates also install the IAC Ask Toolbar. I discuss these installations in this separate section because they raise concerns somewhat different from the IAC toolbars discussed above. I see five key problems with Oracle Java updates that install IAC toolbars:

First, as Ed Bott noted last week, the “Install the Ask Toolbar” checkbox is prechecked, so users can install the Ask toolbar with a single click on the “Next” button. Accidental installations are particularly likely because the Ask installation prompt is step three of five-screen installation process. When installing myriad software updates, it’s easy to get into a routine of repeatedly clicking Next to finish the process as quickly as possible. But in this case, just clicking Next yields the installation of Ask’s toolbar.

Second, although the Ask installation prompt does not show a “focus” (a highlighted button designated as the default if a user presses enter), the Next button actually has focus. In testing, I found that pressing the enter or spacebar keys has the same effect as clicking “Next.” Thus, a single press of either of the two largest keys on the keyboard, with nothing more, is interpreted as consent to install Ask. That’s much too low a bar — far from the affirmative indication of consent that Google rules and FTC caselaw call for.

Third, in a piece posted today, Ed Bott finds Oracle and IAC intentionally delaying the installation of the Ask Toolbar by fully ten minutes. This delay undermines accountability, especially for sophisticated users. Consider a user who mistakenly clicks Next (or presses enter or spacebar) to install Ask Toolbar, but immediately realizes the mistake and seeks to clean his computer. The natural strategy is to visit Control Panel – Programs and Features to activate the Ask uninstaller. But a user who immediately checks that location will find no listing for the Ask Toolbar: The uninstaller does not appear until the Ask install finishes after the intentional ten minute delay. Of course even sophisticated users have no reason or ability to know about this delay. Instead, a sophisticated user would conclude that he somehow did not install Ask Toolbar after all — and only later will the user notice and, perhaps, proceed with uninstall. Half a decade ago I found WhenU adware engaged in similar intentional delay. Similarly, NYAG litigation documents revealed notorious spyware vendor Direct Revenue intentionally declining to show ads in the first day after its installation. (Direct Revenue staff said this delay would “reduce the correlation between the Morpheus download [which bundled Direct Revenue spyware] and why they are seeing [Direct Revenue’s popup] ads” — confusion that DR staff hoped would “creat[e] less of a path to what they [users] should uninstall.”) Against this backdrop, it’s particularly surprising to see IAC and Oracle adopt this tactic.

Fourth, IAC makes changes beyond the scope of user consent and fails to revert these changes during uninstall. The Oracle/IAC installation solicitation seeks permission to install an add-on for IE, Chrome, and Firefox, but nowhere mentions changing address bar search or the default Chrome search provider. Yet the installer in fact makes all these changes, without ever seeking or receiving user consent. Conversely, uninstall inexplicably fails to restore these settings. As noted above, these incomplete uninstalls violate Google’s Software Principles requirement that an “easy” uninstall must disable “all functions of the application.”

Finally, the Java update is only needed as a result of a serious security flaw in Java. It is troubling to see Oracle profit from this security flaw by using a security update as an opportunity to push users to install extra advertising software. Java’s many security problems make bundled installs all the worse: I’ve received a new Ask installation prompts with each of Java’s many security updates. (Ed Bott counts 11 over the last 18 months.) Even if the user had declined IAC’s offer on half a dozen prior requests, Oracle persists on asking — and a single slip-up, just one click or keystroke on the tenth request, will nonetheless deliver Ask’s toolbar.

A security update should never serve as an opportunity to push additional software. As Oracle knows all too well from its recent security problems, users urgently need software updates to fix serious vulnerabilities. By bundling advertising software with security updates, Oracle teaches users to distrust security updates, deterring users from installing updates from both Oracle and others. Meanwhile, by making the update process slower and more intrusive, Oracle reduces the likelihood that users will successfully patch their computers. Instead, Oracle should make the update process as quick and easy as possible — eliminating unnecessary steps and showing users that security updates are quick and trouble-free.

Toolbar Operations and Result Format

Once a user receives an IAC toolbar, a top-of-browser stripe appears in Internet Explorer and Firefox, and IAC also takes over default search, address bar search, and error handling. That’s an intrusive set of changes, and particularly undesirable in light of the poor quality of IAC’s search results.

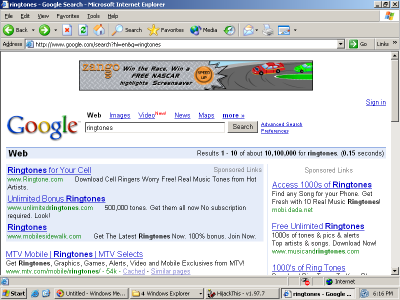

If a user runs a search through an IAC toolbar or through a browser search function modified by IAC, the user receives Mywebsearch or Ask.com results page with advertisements and search results syndicated from Google. The volume of advertisements is remarkable: On a 800×600 monitor, the entire first two screens of Mywebsearch results presented advertisements (screen one, screen two) — four large ads with a total of seven additional miniature ads contained within. The first algorithmic search result appears on the third on-screen page, where users are far less likely to see it. At Ask.com, ads are even larger: fully seven advertisements appear above the first algorithmic result, and three more ads appear at page bottom — more than filling two 800×600 screens.

IAC obtains these advertisements and search results from Google, but IAC omits features Google proudly touts in other contexts. For example, Google claims that its maps, hotel reviews, and hotel price quotes benefit users and save users time — but inexplicably IAC Mywebsearch lacks these features, even though these features appear prominently and automatically for users who run the same search at Google. In short, a user viewing IAC results gets listings that are intentionally less useful — designed to serve IAC’s business interest in encouraging the user to click extra advertisements, with much less focus on providing the information that IAC and Google consider most useful.

The ad format at IAC Mywebsearch and Ask.com makes it particularly likely that users will mistake IAC ads for algorithmic results. For one, IAC omits any distinctive background color to help users distinguish ads from algorithmic results. Furthermore, IAC’s voluminous ads exceed beyond the first screen of results for many searches. A user familiar with Google would expect ads to have a distinctive background color and would know that ads typically rarely completely fill a screen — so seeing no such background color and similar-format results continuing for two full screens, the user might well conclude that these are algorithmic listings rather than paid advertisements.

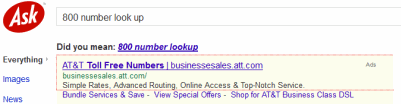

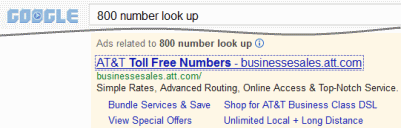

IAC buys traffic from Google and other search engines. The resulting sequence is needlessly convoluted: A user runs a search at Google, clicks an IAC ad purporting to offer what the user requested], then receives an IAC landing page with the very same ads just seen at Google. For example, I searched for [800 number look up] at Google and clicked an Ask ad. The resulting Ask page allocated most of its the above-the-fold space to three of the same ads I had just seen at Google! This process provides zero value to the user — indeed, negative value, in that the extra click adds time and confusion. But IAC monetizes its site unusually aggressively — for example, regularly putting four ads at the top of the page, where Google sometimes puts none and never presents more than three. Of course these extra ads serve IAC’s interest: By pushing a fraction of users to click multiple ads, IAC can more than cover its costs of buying the traffic from Google in the first place.

Longstanding Google rules exactly prohibit IAC’s search arbitrage. Google’s AdWords Policy Center instructs that “Google AdWords doesn’t allow the promotion of websites that are designed for the sole or primary purpose of showing ads.” Google continues: “One example of this kind of prohibited behavior is called arbitrage, where advertisers drive traffic to their websites at low cost and pay for that traffic by earning money from the ads placed on those websites”

Why isn’t Google enforcing its rules against arbitrage? An October 2012 Search Engine Land article quotes a reader who wrote to Google AdWords support, where a representative replied with unusual candor: “Since Ask.com is considered a Google product, they are able to serve ads at the top of the page when the search query is found to be relevant to their ads.” Of course Ask.com is not actually “a Google product” — it’s a Google syndicator, showing Google ads in exchange for a revenue share, just like thousands of other sites. But with IAC reportedly Google’s biggest advertising customer, special privileges would be less than surprising. Meanwhile, Google lets IAC do Google’s dirty work — showing extra ads to gullible users — which could let Google collect additional ad revenue from those users’ clicks. Still, that’s no help to users (who get pulled into extra page-views and less useful pages with more advertisements) or advertisers (whose costs increase as a result). And once the public recognizes Google’s role in authorizing this scheme, selling all advertising, and funding the entirety of IAC’s activity, Google ends up looking at least as culpable as IAC.

Ads with Oversized Clickable Areas

Contrary to standard industry practice and Google rules, IAC makes the entire ad — including domain name, ad text, and large whitespace — into a clickable link. Notice the large clickable area flagged in the red box.

Contrary to standard industry practice and Google rules, IAC makes the entire ad — including domain name, ad text, and large whitespace — into a clickable link. Notice the large clickable area flagged in the red box.

At Google, only the ad itself is clickable. Not the much smaller red box.

At Google, only the ad itself is clickable. Not the much smaller red box.

IAC’s ads also flout industry practice and Google rules as to the size of an ad’s clickable area. Both in arbitrage landing pages and in toolbar results, IAC’s search result pages expand the clickable area of each advertisement to fill the entire page width, sharply increasing the fraction of the page where a click will be interpreted as a request to visit the advertiser’s page.

See the screenshot at right. (To create the red-outlined box showing the shape of the clickable area, I clicked an empty section of the ad and began a brief drag, causing my browser to highlight the ad’s clickable area in red as shown in the screenshot.)

Ask is an outlier in converting whitespace around an ad into a clickable area. Every other link on Ask.com landing pages — every link other than an advertisement — follows standard industry practice with only the words of the link being clickable, but not the surrounding whitespace. Indeed, at Google, Bing, and Yahoo, white space is never clickable. At Google and Bing, only ad titles are clickable, not ad domain names, or ad text. (See Google screenshot at right, showing the limited clickable area of a Google ad.) At Yahoo, only ad titles and domain names are clickable, not ad text or white space.

IAC has taken intentional action to expand its ads’ clickable area to cover all available width. As W3schools explains, “A block element is an element that takes up the full width available.” To expand ad hyperlinks to fill the entire width, Ask tags each ad hyperlink with the CSS STYLE of display:block.

<a id=”lindp” class=”ptbs pl20 pr30 ptsp pxl” style=”display:block;padding-bottom: 0px;” …

Google’s rules prohibit IAC’s expanded clickable areas. Google requires that “clicking on space surrounding an ad should not click the ad.” Yet IAC nonetheless makes a clickable area out of the area surrounding each ad, extending all the way to the right column.

IAC’s expanded ads invite accidental clicks. Accidental clicks are particularly likely from the inexperienced users IAC systematically targets for toolbar installations, and also from users searching on tablets, phones, and other touch devices. These extra clicks waste users’ time and drive up advertisers’ costs — but every such click yields extra revenue for IAC and Google.

Google should enforce its rules strictly. No doubt IAC can offer Google some short-term revenue via extra ad-clicks from unsophisticated or confused users. But this isn’t the kind of business Google aspires to, and Google’s public statements indicate no interest in such bottom-feeding. Indeed, a fair application of Google’s existing AdWords rules would disallow both IAC’s toolbar ads (using AdWords to solicit installations) and IAC’s search arbitrage ads (using AdWords to send users to IAC pages presenting syndicated AdWords ads). Meanwhile, numerous Google AdSense rules are also on point, including prohibiting encouraging accidental clicks, prohibiting site layout that pushes content below the fold, and limiting the number of ads per page. So too for Software Principles requiring up-front disclosure as well as “easy” and complete uninstall.

As a publicly-traded company, IAC should benefit from the oversight and guidance of its outside directors. But the New York Times commented in 2011 that “IAC’s board is filled with high-powered friends of Mr. Diller,” calling into question the independence and effectiveness of IAC’s outside directors. Of particular note is Chelsea Clinton, who joined IAC’s board in September 2011. Ms. Clinton’s prior experience includes little obvious connection to Internet advertising or online business, suggesting that she might need to invest extra time to learn the details of IAC’s business. Yet she also has weighty commitments including ongoing doctoral studies, serving as an Assistant Vice Provost at NYU, and reporting as a special correspondent for the NBC Nightly News — calling into question the time she can devote to IAC matters. The Times questioned why IAC had brought in Ms. Clinton, concluding that “This is clearly an appointment made because of who she is, not what she has done.” Indeed, Ms. Clinton’s background means she will be held to a particularly high standard: if she fails to stop IAC’s bad practices, the public may reasonably ask whether she has done her duty as an outside director.

Recent research from Goldman analyst Heath Terry flags investor concerns at IAC’s tactics. In a December 4, 2012 report, Terry downgraded IAC to sell due to vulnerability from Google policy changes. A January 9, 2013 follow-up noted IAC changing its uninstall practices to comply with Google policy as well as slowdown in arbitrage. Terry flags some important factors, and I share his bottom line that IAC’s search practices are unsustainable. But the real shoe has yet to drop. If Google is embarrassed at IAC’s actions — and it should be — Google is easily able to put an end to this mess.

I prepared a portion of this article at the request of a client that prefers not to be listed by name. The client kindly agreed to let me include that research in this publicly-available posting.