Zango often touts its so-called “content economy” — purportedly providing users access to media in exchange for accepting Zango’s popup ads. After four years of debunking Zango’s claims, I’ve come to suspect the worst — and my investigations of Zango’s media offerings confirm that Zango’s media library is nothing to celebrate. This article reports the results of my recent examinations. I show:

- Widespread copyrighted video content presented without any indication of license from the corresponding rights-holders. Details.

- Widespread sexually-explicit material, including prominent explicit material nowhere labeled as such. Details.

- An audio library consisting solely of prank phone calls to celebrities (without the “music” Zango promises). Details.

- Widespread material users can get elsewhere for free, without any popups or other detriments. Details.

- Widespread material that content creators never asked to have included in any Zango library. Details.

Widespread copyrighted video content presented without any indication of license from the corresponding rights-holders

Many of the videos in of Zango’s video library are the work of major movie studios, TV networks, and other third parties that own and assert copyright in their respective works. These videos consistently appear without any statement of authorization (e.g. “used with permission”) or even the ordinary copyright notice. I therefore conclude that Zango’s site features these videos without authorization from the corresponding rights-holders.

For many videos in Zango’s library, it is trivially easy to determine the video’s source. For example, text in the corner of Zango’s “Ashley Judd Nude Photoshoot” indicates the video comes from “Norma Jean & Marilyn” (1996, released on DVD by HBO Home Video). The title of Zango’s “Wild Things” suggests the video comes from the 2004 Sony Pictures movie by the same name; watching the video confirms the match. Zango’s “Girls Next Door Nude Compilation” begins with the distinctive Playboy logo. Zango’s “Chris Rock on the Daily Show” reproduces a video clip from Comedy Central’s Daily Show. It’s easy to find scores of other examples plainly labeled as well-known copyrighted works.

Other videos in Zango’s library are harder to identify — at least those without extensive entertainment industry experience. For example, I cannot easily determine the specific movie that included the scenes shown in Zango’s “Paris Hilton Striptease” or “Rachel Hunter in the Bathtub.” But the clips leave little doubt that they were filmed professionally and that the respective studios hold copyright in the resulting works. Similarly, I cannot easily determine the specific source of Zango’s “Branding Beat Down.” However, every frame of the video bears the distinctive Fox logo — indicating that the video originated with the Fox Broadcasting Company.

As to at least eight of the files in Zango’s library, I have specifically confirmed that Zango’s reproduction occurs without authorization from the underlying rights-holders. (Details below.) As to selected other files, I have sent inquiries to the corresponding rights-holders. I will update this page if I confirm whether Zango has properly licensed the content at issue.

Infringing videos are remarkably prominent in Zango’s video library. For example, as of May 27, Zango’s home page linked to “Borats First Trip To An American Gym” (s.i.c.). This clip was listed as the second most popular video in Zango’s entire content library, and it was placed in the top-center of Zango’s main www.zango.com web page, “above the fold” (within the portion of the page visible without using scroll bars). Yet the title of the video plainly indicates that the video contains the copyrighted work of others. Moreover, the video features the “DIVX Video” logo, indicating that DivX software was used to extract (“rip”) the video from a DVD. No authorized reproduction would be provided with a DivX overlay, so the presence of the DivX marker confirms that this video was reproduced without permission from the creators of Borat.

Other online video sites have been the target of major copyright litigation. For example, Viacom last year sued Google, alleging that “YouTube appropriates the value of creative content on a massive scale for YouTube’s benefit without payment or license.” In defense, Google points out that YouTube receives videos from independent — potentially granting Google immunity for these infringements due to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act‘s safe harbor for infringements occurring at the direction of users (17 USC 512(c)(1)).

Unlike YouTube, Zango’s video library offers no prominent “upload” function. Some of Zango’s videos arrive through the Revver video-sharing service (discussed below), probably originating with a variety of independent users. But many of the copyrighted videos Zango offers reside on Zango’s servers, not on Revver servers. (For example, all eight of the sexually-explicit videos linked in the first paragraph of the next section are hosted on Zango servers.) Because Zango offers no “upload” function by which ordinary users could have put videos onto Zango’s site, it therefore appears that these videos were provided by Zango or its agents, not by independent users. If so, Zango will not find protection in the DMCA’s safe harbor for infringements caused by users.

Moreover, even if Zango’s videos were provided by independent users, the circumstances of the reproduction seem to render Zango ineligible for the DMCA safe harbor. For one, the safe harbor requires that Zango lack actual knowledge of the infringements. But the infringing videos were obvious and self-evident, not just from their titles and contents, but also from their prevalence in featured results Zango chose to highlight. In addition, the safe harbor requires that Zango not receive a financial benefit directly attributable to the infringements. But Zango used these videos to induce users to download its popup-generating software, a financial benefit that is directly attributable to the infringing videos. (Consider the case of a user who installs Zango in response to solicitation offering a specific copyrighted video clip. Example.) Furthermore, Zango has the right and ability to control the infringement (e.g. by removing the infringing videos). Because Zango’s financial benefit can be directly tracked to a specific infringement, and because Zango has the right and ability to prevent such infringement, Zango seems to fail the test in 17 USC 512(c)(1)(B).

Zango may claim that its videos are fair use. The Copyright Act sets out a four-factor test for determining whether reproduction of a copyrighted work is permissible, despite lack of authorization from the rights-holder. The fair use test calls for considering 1) the purpose and character of the use (e.g. whether commercial or nonprofit), 2) the nature of the copyrighted work, 3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used, and 4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for the work. Factor one is easy: Zango’s use is clearly commercial, which tends to cut against a finding of fair use. Zango might claim that its presentation of excerpts (rather than entire movies) supports a finding of fair use under the third test — but Zango exactly chooses what it views as highlights (e.g. the explicit portions of full-length movies), yielding clips with a greater than usual effect on the potential market for the underlying works. In short, a fair use defense is at best uncertain.

Wide-scale copyright infringement could expose Zango to substantial liability. The Copyright Act provides for statutory damages of “not less than $750” per violation. My examination indicates Zango is reproducing (at least) hundreds of copyrighted videos without any statement of authorization. Furthermore, such videos have surely been downloaded repeatedly — giving rise to potential statutory damages that could easily reach seven digits or more.

Widespread sexually-explicit material, including prominent explicit material nowhere labeled as such

Browse Zango’s video library, and it’s easy to find sexually-explicit video. As shown in the first inset image at right, the bottom-right corner of each Zango “Browse” page gives a list of celebrities — each of them female, each featured in various states of undress. Among other explicit videos of these celebrities, Zango offers “Britney Spears See Thru“, “Britney Spears Black Dress Upskirt“, “Paris Hilton Striptease“, “Rachel Hunter in the Bathtub“, “Jessica Alba’s Chest and You“, “Jessica Simpson Nipple Slip“, “Anna Kournikova Panties Oops“, and “Angelina Jolie Sex Scene.”

The titles and descriptions of many of Zango’s videos suggest that their subjects were unwilling participants. See e.g. “nipple slip” and “upskirt” above, as well as additional videos like Zango’s “Arab wife’s sexy dance secretly taped” and Zango’s “Girlfriend Finds Hidden Camera.”

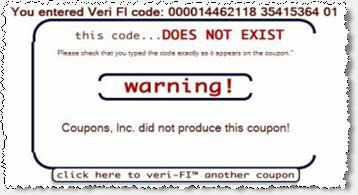

Through its placement and labeling of sexually-explicit videos, Zango creates a substantial risk that users will receive explicit materials they did not seek. For example, on May 24, I clicked “Browse” to flip through Zango’s content library. Using Zango’s default sort, the third video was entitled “the pool” with comment “havin fun in the pool” (s.i.c.). (Screenshot of the link from within Zango’s video library.) This title and comment give no indication that the resulting material is explicit. But clicking the “Watch” button immediately yields a large video showing two male adults swimming nude, then exiting the pool (entirely disrobed). As best I can tell, Zango did nothing to alert users to this explicit material, nor does Zango prevent (or even discourage) children from viewing such material.

Zango’s May 24 “the pool” video was not a mere anomaly. The same video remained linked in the same way in my tests on May 25 and 26, and on portions of May 27.

In litigation documents, Zango last week claimed that it never distributes explicit material to those do not want it. In particular, Zango argues: “Zango never sends unwanted links to pornography web sites” and “Zango only directs adult-oriented advertisements to a user after that user, by his own behavior, has demonstrated interest in such content.” I disagree. The preceding paragraphs offer a counterexample — Zango prominently providing a link to sexually-explicit materials, and provideing that links to users who never demonstrated interest in any such content. Zango may claim that these links tout videos — not a “web site” as in the first quoted sentence. Alternatively, Zango may claim that the links are not “advertisements” — hence beyond a strict reading of the second quoted sentence. But the underlying contradiction remains: Zango says it doesn’t provide pornography except when users seek it; yet in fact Zango does sometimes deliver explicit materials unrequested.

That Zango funds and distributes sexually-explicit materials is well-known. See e.g. the Sunbelt Blog’s February 2008 conclusion that “80% of [Zango’s] business comes from Seekmo, the porn side of its business.” See also Sunbelt’s off-hand November 2006 remark that “hardcore porno videos [are] funded through Zango Seekmo installs.”

But the scope of explicit materials within Zango’s video library is quite striking. Consider the first page of Zango’s library listings for Angeline Jolie. Beyond the “sex scene” video linked above, the listings also include “Angelina Jolie Taking a Bath”, “Angelina Jolie Under the Sheets”, “Angelina Jolie in Bra & Panties”, “A fairly long nude scene staring Angelina Jolie” (s.i.c.), “Angeline Jolie Getting It On”, “Angelina Jolie Nip Slip”, “Angelina Jolie Hardcore”, and “Angelina Jolie Dominatrix”, and “Angelina Jolie Hot On The Runway.” That’s ten explicit results out of twenty links — suggesting that explicit materials are remarkably widespread on Zango’s site.

The initial version of this article also flagged Zango’s “Nice But” (s.i.c.), a video that on May 27 occupied the fourth-most prominent position in Zango’s “Browse” listings. The thumbnail image of this video appeared to feature a full-screen display of a man’s naked buttocks, filling the entire screen. In a follow-up, Zango points out that in fact, the video shows an extreme close-up zoom of of two hands. So this image and video are not actually explicit. Yet a viewer merely flipping through Zango’s listings would nonetheless see an image that is, by all indications, explicit. The title “but” (s.i.c.) and the keyword “naked,” both adjacent to the thumbnail, reinforce the user’s perception of having seen an unrequested explicit image. Although the image is not actually explicit, the image’s content, placement, and labeling make it likely to leave users with the same feeling as an unrequested image that is actually sexually explicit: In both instances, a viewer who merely sees the image and does not watch the video will think he has seen an unwanted explicit image. In my view, Zango errs in mocking this harm. To the users who Zango tricks, the harm is perfectly real.

Zango’s audio library consists solely of prank phone calls to celebrities

Zango’s content library offers three types of media: Videos, screensavers, and audio. Despite Zango’s much-touted “content economy,” Zango offers just eight audio clips. And although Zango’s “About Zango” description promises to provide free access to “music,” in fact all eight of these audio files are recordings from talk radio — just voices, with no music at all.

All eight of Zango’s audio recordings share a common theme: Prank phone calls to celebrities. In each, a caller pretends to be someone famous (e.g. the Prime Minister of Canada), and calls a celebrity (e.g. Bill Gates) under the guise of a bona fide discussion. The caller proceeds to berate the celebrity (e.g. by criticizing the features and reliability of Windows).

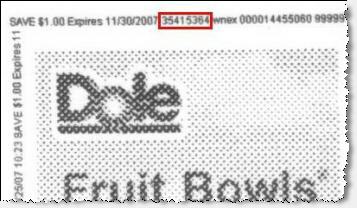

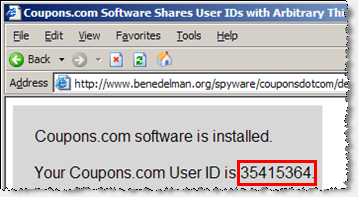

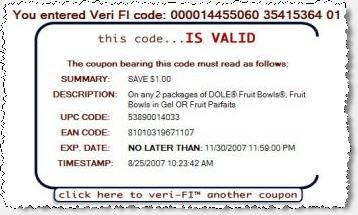

A comment in several of the videos reveals the source of the recordings: The Masked Avengers, which Wikipedia describes as “a Canadian radio duo … of disk jockeys and comedians Sebastien Trudel and Marc-Antoine Audette, known for making prank calls to famous persons by pretending to be government officials or officers in charitable organizations.” I wrote to Mr. Trudel, who confirmed to me that he has not granted Zango any license to use or reproduce these clips.

After placing these recordings in its content library, Zango further syndicates the materials onto Zango’s partner sites. For example, celebsprankd.com (screenshot) features all eight recordings, but requires users to install Zango before listening. Whois reports that Celebsprankd comes from the Vancouver, B.C. advertising firm Neverblue Media — a conclusion confirmed by the presence of the Neverblue.com web server at the same IP address. Neverblue describes itself as a “leading … online marketing company” offering “premier” advertising and “solid business leads” — claims arguably inconsistent with distributing and profiting from prank phone calls, not to mention distributing Zango. (But these recordings aren’t Neverblue’s only tie to Zango. This month alone, my Automatic Spyware Tester found eleven incidents of Neverblue affiliates buying popup traffic from Zango. I’ve also found dozens more incidents as to Neverblue affiliates buying traffic from other spyware.)

What of Zango’s distribution of these prank call recordings? With so few clips yet such prominent placement (including five of these eight audio recordings featured on Zango’s home page), senior Zango staff surely know what the files contain. Does Zango support prank phone calls? Wasting celebrities’ time under false pretenses? Recording phone calls without permission, even in states that specifically require such permission? It’s hard to reconcile these practices with Zango’s supposed reforms.

Widespread material users can get elsewhere for free, without any popups or other detriments

Much of Zango’s content is available elsewhere without charge and without installing any software that tracks online behavior or shows popup ads. For example, clicking Zango’s “Browse” tab and retaining defaults, every single video on the first page of results is syndicated from Revver. Users could just as easily get these videos directly from Revver, as receive them from Zango. But if users watched these videos at Revver, Zango’s software would not track their web browsing and searching, and users would not receive Zango’s popup ads.

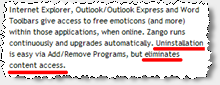

Furthermore, Zango makes untrue claims about the necessity of its software. For example, Zango claims that “uninstallation … eliminates content access.” It does not. For files hosted at Revver, installation of Zango is not necessary to watch the videos in the first place, and uninstallation does not interfere with watching the videos later. Moreover, even many Zango-hosted files can be accessed without installing Zango, or after uninstalling Zango. For example, Zango’s “Chris Rock on the Daily Show” is actually just a standard Windows Media Video (WMV) distributed from the following URL: preview.licenseacquisition.org/123/1054944882.36393/yikers_chris_rock_on_the_daily_show.wmv . Zango’s “Borats First Trip To An American Gym” (s.i.c.) is preview.licenseacquisition.org/123/1054944854.02531/yikers_borats_first_trip_to_an_american_gym.wmv . Similarly, Zango’s “Bill Gates Gets Pranked” is a WMA hosted at preview.licenseacquisition.org/13/12295/12295.wma . Any user who knows these URLs can easily receive the corresponding files — without ever installing Zango, or after uninstalling Zango. Zango ought not claim otherwise.

Presenting material that content creators never asked to have included in any Zango library

By syndicating videos from Revver, Zango causes its video library to feature materials that content creators never asked to have associated with Zango in any way.

Zango’s syndication of Revver videos has prompted numerous complaints content creators who post videos to Revver. For example, Chris Pirillo asked why his videos are appearing on Zango. (“I don’t remember giving Zango permission to push crapware on my behalf.”) Revver forum user JPPI pointed out the irony of Zango claiming his videos were “FREE, thanks to Zango” when in fact the videos were free all along (even before Zango syndicated them). Revver forum user David complained that it is “kinda deceptive” (s.i.c.) “to make it sound like Zango was the one who made the video free.”

In response, Revver Vice President Asi Behar agreed to ask Zango to remove any Revver videos that Revver authors specifically so designate. But such removals do nothing to cure the deception of Zango requiring that users install its software before watching materials widely available elsewhere for free. Furthermore, such removals do nothing to protect Revver content creators who are unaware of Revver’s relationship with Zango. The word “Zango” appears nowhere on Revver’s official web site (as distinguished from Revver’s forums and some Revver-hosted videos). Thus, a Revver content creator has no easy way to learn about Revver’s relationship with Zango — not to mention learn of the option to request exclusion from Zango.

Zango’s syndication of Revver videos risks tainting the good name of Revver content creators. Consider a user who searches for a Revver video and finds that video hosted at Zango (just as Chris Pirillo did last year). The user may mistakenly conclude that installing Zango is in fact necessary to watch the video. If so, the user is likely to end up with a negative view of the underlying content creator — mistakenly concluding that, e.g., Chris Pirillo has partnered with Zango or endorses Zango’s activities. Revver forum complaints indicate that numerous Revver users share this concern. Yet Revver continues to syndicate videos to Zango without first checking with content creators.

Last week, Zango was one of four finalists for the Software & Information Industry Association’s CODiE Best Video Content Aggregation Service. In my view, that award is misguided: Far from deserving praise, Zango should be criticized and shunned for reproducing others’ copyrighted work without any apparent license to do so, showing sexually-explicit material unrequested, and offering users a lousy value by bundling extra ads with content users could get elsewhere for free.

Meanwhile, Zango continues litigation with Kaspersky. Recall: Kaspersky blocked Zango’s software from installing; Zango sued; Kaspersky successfully defended on the grounds that the Communications Decency Act, 47 USC 230, immunizes Kaspersky’s behavior because Kaspersky is an “interactive computer service provider” blocking material that, in its subjective opinion, is “objectionable.” In Zango’s appeal, Zango claims its software is not “otherwise objectionable” (brief pages 12-15; PDF pages 17-20). If it’s not objectionable to show explicit material unrequested — not to mention to infringe copyrights on a massive scale, and to insert extra ads around material available elsewhere without such ads – then I don’t know what is.

Finally, I’m often asked whether Zango continues the behaviors I previously reported. Installing through sneaky fake-user-interface pop-up ads that mimic the appearance of official Windows dialog boxes (as I reported last summer)? Yes. I made a fresh video showing such installations just last week.Defrauding advertisers through popups that cover merchants’ sites with their own affiliate offers(as I reported last spring, in September 2005, in summer 2004, and otherwise)? Definitely. This month alone, I reported six Zango incidents to just one of my advertiser clients — not to mention scores of other incidents targeting other web sites and advertisers. Zango repeatedly claims its problems are all in the past, but my hands-on testing continues to indicate otherwise.

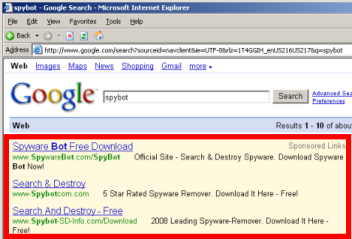

SiteAdvisor markup of search results, flagging a representative Google ad — asking users to pay for software widely available elsewhere for free.

SiteAdvisor markup of search results, flagging a representative Google ad — asking users to pay for software widely available elsewhere for free.