180solutions today announced its plan to show its users “notification” popups describing some of 180’s practices — thereby, in 180’s view, obtaining users’ “informed consent.” In principle, a re-opt-in might let 180 obtain users’ consent even where initial installations had somehow failed to do so. But 180’s notification message is so flawed and so duplicitous that it can’t offer the legitimacy 180 purportedly seeks. For one, 180’s notification screen makes numerous false statements. Also, 180’s notification is presented in a way that fails to obtain any notion of “consent.” Meanwhile, even 180’s new installs don’t obtain meaningful informed consent.

A Close Look at 180’s “Notifications”

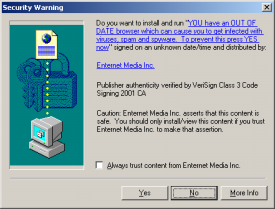

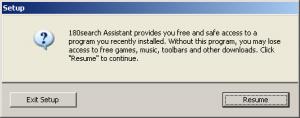

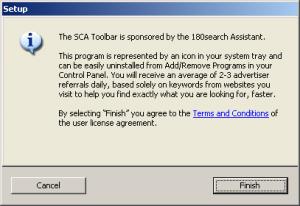

180 Notification Screenshot

A reporter yesterday sent me a screenshot of 180’s planned notification. I see at least seven problems with the screen’s text:

1. 180’s notification screen fails to affirmatively state what 180 does — its popups or its privacy effects. 180’s first two sentences disclose that something called “180search Assistant” is installed, and that it will show “ads.” But nowhere does 180 disclose that the ads appear in popups — an advertising format known to be particularly objectionable, and therefore particularly important to bring to users’ attention if users are to offer genuine consent. In addition, nowhere does 180 disclose the important privacy effects of installing 180 software — that 180 will track what web sites users visit, and send much of this information to its servers. The importance of these omissions can’t be overstated: If 180 fails to disclose what users are purportedly accepting, no valid “consent” can result.

2. 180 claims to “giv[e] you free access to search tools, software and entertainment sites.” This claim is false, in that for many users 180 provides no such thing. Consider a user who receives 180 software without notice or consent. 180 might allow access to special entertainment sites that are otherwise unavailable. But this ability is of no benefit if users don’t know they have 180, didn’t ask for 180, aren’t told what special sites they can access, and in any event don’t want to access such sites.

3. 180 claims to show “approximately 2-3 highly targeted ads per day.” This claim is false, in that many users will receive many more ads per day. Perhaps an average user gets only a few ads per day, when averaging includes all the users who don’t use their PCs on many days, or who don’t use their web browsers. But in even limited web browsing, I consistently receive far more than three 180 ads per day.

4. 180 inexplicably claims that “user consent is required before 180search Assistant can be installed.” This claim is absolutely false. 180 is often installed without any consent at all. See videos on my site (1, 2, 3) (dozens more on file). 180’s own staff have repeatedly admitted that nonconsensual installations occur (1, 2, 3, 4). After these many admissions, I don’t understand how 180 can now argue that users have “consent[ed]” to its installation. Indeed, the entire premise of 180’s re-notification program is to make up for prior nonconsensual installations!

5. 180 claims that “all 180search Assistant ads are labeled…” This is false. As 180 staff have previously admitted, advertisements with redirects erase 180’s ad labeling.

6. 180 claims that “the user must be 18 or over to download.” Again, false. In fact, 180 software is widely offered on kids sites, where users are unlikely to be over 18. (Example.) Some 180’s installations mention a requirement of user age, but this provision is typically exceptionally hard to find. For example, in one screensaver I tested today, the user-age provision was on page 18 of 180’s license, in the next-to-last paragraph, captioned “Miscellaneous.” (Screenshot.)

7. 180 concludes by claiming that “You can easily remove the 180search Assistant … using ‘Add or Remove Programs'” False. The removal isn’t “easy,” for at least two reasons.

i. Finding 180 is surprisingly difficult. 180 often places its entry in tricky locations within the alphabetical Add/Remove listing — like under “U” for “Uninstall 180search Assistant,” rather than a more natural “1” for “180search Assistant.” Users cannot reasonably be expected to look under “U” in search of 180’s entry. On a new PC with a short Add/Remove list, users will still typically find 180’s entry. But on a long and crowded Add/Remove list, on a typical heavily-used PC, it’s anything but “easy” to find 180.

ii. 180 discourages removals using various false and misleading statements. See my prior analysis, finding numerous dubious claims in 180’s uninstall procedure, as well as confusing window design that further discourages removal. For example, 180 falsely claims that removing its software “will disable any Zango-based applications” — even when no such applications have been installed.

Combining these factors, 180’s uninstall procedure is not properly characterized as “easy.” 180 does know how to make “easy” procedures: When 180’s software is installed with one click (or even with zero!), the procedure is remarkably simple. But 180 has taken affirmative steps to make removal harder.

Problems with 180’s Notification Procedure: Failing to Request or Obtain Consent

180’s press release claims that its new notification screens will “ensure each user … has provided informed consent.” I disagree. As I look at 180’s notification text, 180’s notification actually won’t obtain any consent at all.

As a threshold matter, 180’s notifications apparently will be shown in ordinary Internet Explorer popup windows. Seeing these popups, typical users will seek to close them as quickly as possible — finding them irrelevant, unwanted, and annoying. The ordinary IE presentation format is not conducive to obtaining consent. It’s certainly not well-equipped to get the “informed consent” 180 purports to seek.

Most seriously, 180’s notification text does not seek or require any manifestation of user agreement or approval. In fact, 180’s screen doesn’t say anything about consent: It doesn’t require users to click a button to indicate acceptance of 180’s terms; it doesn’t require users to click a button to keep 180 software on their PCs. Rather, 180’s software stays installed unless users figure out how to remove it. Failure to remove 180’s software certainly can’t be claimed to constitute “consent” to keep it installed. So where’s the “consent” in 180’s notifications?

If 180 really wants informed consent, it could do a lot better. Rather than write its notification screens in marketing-speak, full of euphemisms and half-truths, 180 could write its notification in the formal and calm language used in disclosures elsewhere. I’ll even give 180 a few free sentences. First, 180 should accurately describe its software:

“Your computer is running 180solutions advertising software. 180 will track what web sites you visit, and 180 will show you pop-up ads accordingly. On average, users receive several ads per day, but you may receive more or fewer, depending on how often you use your web browser and depending on what web sites you visit.”

180 would accompany this text with an image showing a representative pop-up ad.

Next, 180 would proceed to explain how its software got installed, and what users can do to keep it or to remove it:

“180 software may have been installed on your computer with your consent or with consent of another user of your computer. 180 may have become installed without consent. You may elect to keep 180 software on your PC, or you may choose to remove it without penalty.”

Finally, 180 would include a one-click button to uninstall its software immediately, along with another button that indicates users’ consent to keep 180 installed.

If 180 included notice of this form — unbiased truthful sentences, that fairly and frankly disclose 180’s true effects — users might be able to make an informed decision to keep 180’s software. But where 180’s “disclosure” is loaded with euphemisms and falsehoods, offering only a convoluted uninstall procedure, it’s hard to say 180 has obtained “informed consent.”

180’s New Installation Stubs: Half-Truths and Omissions

180’s press release claims that its new “technology enhancements” will make it “harder” for 180 software to be installed “covert[ly].” Perhaps. But what happened to the standard of “informed consent” (so prominent earlier in 180’s press release)? 180’s change in wording — from “informed consent” to avoiding “covert” installations — may be surprisingly important. I agree that 180’s new installation procedure isn’t covert. But neither does it yield informed consent.

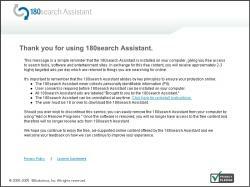

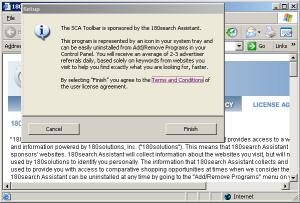

180 Stub Installer – Main Screen

180 Stub Installer – Main Screen

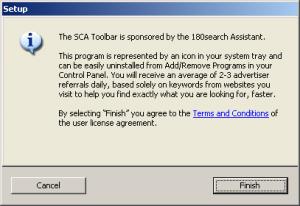

Installer Covers & Obscures License Agreement

Installer Covers & Obscures License Agreement

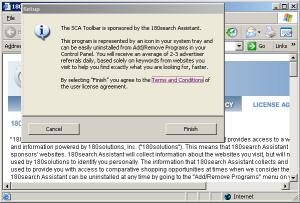

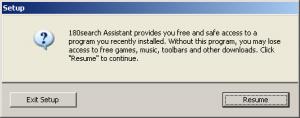

Secondary Installer Screen – If User Initially Declines

Secondary Installer Screen – If User Initially Declines

My understanding is that the “enhancement” at issue is a stub installer like that shown at right. 180’s distribution partners currently distribute a full copy of 180 software. But in the future, apparently they’ll only distribute a stub. Currently, 180’s partners are asked to obtain consumer consent for the installation of 180 software; under the new approach, 180 itself will obtain consent. If properly implemented, this approach might prevent many wrongful installations. Unfortunately, I’ve seen little sign that 180 has designed this system in a way that obtains meaningful consent.

Last week I was testing a security hole exploit which installed more than a dozen programs on my test PC without any notice or consent. Among the unrequested screens appearing on my test PC was the image shown at right (top). This first screen apparently seeks my consent to install 180 — but like the 180 notification described in the preceding sections, nowhere does this screen explain 180’s relevant characteristics and effects. The screen mentions “180search Assistant” and “2-3 advertiser referrals” — but nowhere does it mention that 180’s “referrals” are actually pop-up ads. The screen says that referrals will be “based … on … websites you visit,” but it fails to disclose that website visit data will also be sent to 180’s servers. So the screen fails to mention the relevant facts users need to know in order to grant informed consent.

180’s stub installer does mention an external license, available via a blue link from within the stub. I clicked the link and received the image shown in the second screen at right. Notice the web browser showing 180’s license — in a small window, requiring eight screens to view in full. Worse, although I had clicked the “Terms and Conditions” link to request the license, 180’s large stub installer still largely covered the license. It was extraordinarily hard to read the license, even when I maximized the license to fill the rest of the screen, because roughly half of each line of text was covered by the stub window. (Notice that the license window is “active” (blue title bar highlighting) while the stub “Setup” window is “inactive” (grey).) This is not a one-time fluke; to the contrary, the stub consistently remains on top of the license (and all other windows), contrary to Windows standards. Savvy users may realize they can move the stub out of the way by dragging its title bar. But the ordinary windows Minimize button is missing from the stub’s window, eliminating the easiest way to hide that screen.

On one test PC, I pressed “Finish” in the stub, and 180 installed immediately.

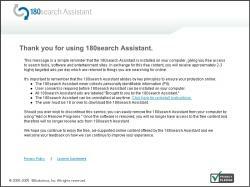

On another test PC, I mimicked the choice of a user who didn’t want 180. I pressed “Cancel” in the stub, and I was then shown the third screen at right. This window claims that “without [180], [a user] may lose access to free games, music, toolbars, and other downloads.” This statement may be accurate as to some installations, but in the security exploit I received last week, I had requested no games, music, toolbars, or other download — so there could be no loss of access in the way the dialog box claimed. This statement was therefore false, as applied to me.

Consider a user who presses “Cancel” in the first screen, but then decides to give 180 a second chance on the strength of the second dialog. When the user presses “Resume” in the second box, the user has not yet accepted 180’s license agreement — probably failing to read it initially (since the user decided to press Cancel, not wanting 180) and certainly failing to accept it. Nonetheless, 180 immediately installs, without offering any further opportunity for a user to access the license or to decline installation. So in 180’s view, the “Resume” button in the second box actually means “I accept the license linked from the prior box but not available on this screen.” That’s a tall order — certainly not what the box plainly says, or what typical users will expect to occur if they press Resume.

Here too, 180 could do much better. 180 could provide a clear description of its effects, using ordinary terms (“pop-up ads”) users can readily understand. 180 could present its installation request with appropriate branding — colors, logo, font, and other characteristics that match 180’s other marketing material. 180 could present its license in a way users can readily read. And 180 could refuse to install when user consent is at best ambiguous (“resume”).

180 is promoting this “stub” installation procedure as a solution to nonconsensual installs. If all 180’s distributors switch to this new installation method, perhaps fewer distributors will be able to infect users in complete silence. But the stub’s tricky text and poor disclosures mean users will still receive 180 software without being fairly told what it is and what it will do to their computers. That’s a far cry from the “informed consent” 180’s press release promises.

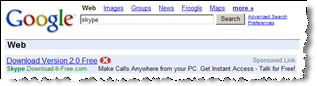

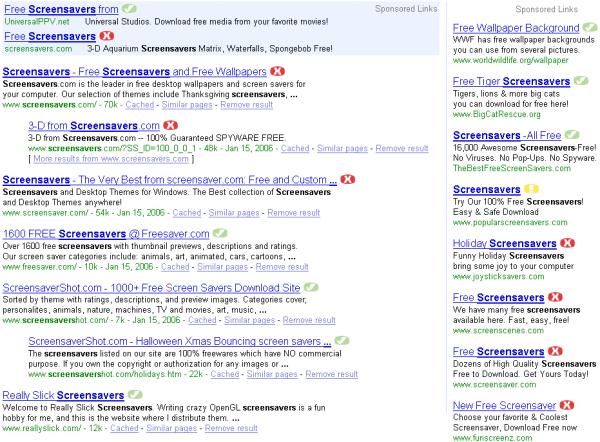

SiteAdvisor markup of search results, flagging a representative Google ad — asking users to pay for software widely available elsewhere for free.

SiteAdvisor markup of search results, flagging a representative Google ad — asking users to pay for software widely available elsewhere for free.

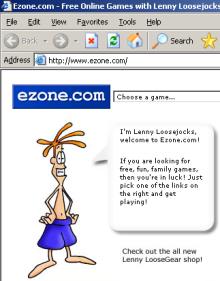

Can we say that a user “consents” to an installation if the installation occurred after a user was presented with a misleading advertisement that looked like a Windows dialog box? If that advertisement was embedded within a site substantially catering to children? If that advertisement offered a feature known to be duplicative with software the user already has? If “authorizing” the installation required only that the user click on an ad, then click “Yes” once? If the program’s license agreement was shown to the user only after the user pressed “Yes”? These are the facts of recent installations of Claria software from ads at games site Ezone.com.

Can we say that a user “consents” to an installation if the installation occurred after a user was presented with a misleading advertisement that looked like a Windows dialog box? If that advertisement was embedded within a site substantially catering to children? If that advertisement offered a feature known to be duplicative with software the user already has? If “authorizing” the installation required only that the user click on an ad, then click “Yes” once? If the program’s license agreement was shown to the user only after the user pressed “Yes”? These are the facts of recent installations of Claria software from ads at games site Ezone.com.