In August I reported a startling number of notorious spyware programs receiving payments, directly or indirectly, from Yahoo!’s pay-per-click (PPC) (Overture) search system. Yahoo pays numerous other companies to show these ads via syndication relationships. So when a spyware vendor can’t find advertisers to buy its ad inventory directly, the spyware vendor can show Yahoo ads instead. Every time a user clicks on such an ad, the advertiser must pay Yahoo. Then Yahoo pays a revenue share to the spyware vendor that showed the ad. My August article documented relationships between Yahoo and 180solutions, Claria, Direct Revenue, eXact Advertising, IBIS, and SideFind.

My August article covered “just a few of the … examples I have observed and recorded.” Since then, my Yahoo-spyware collection has grown dramatically. I now have many dozens of different examples of Yahoo pay-per-click ads shown within spyware.

My August examples demonstrate what I call “syndication fraud” — Yahoo placing advertisers’ ads into spyware programs, and charging advertisers for resulting clicks. But Yahoo’s spyware problems extend beyond improper syndication. In my August syndication fraud examples, an advertiser only pays Yahoo if a user clicks the advertiser’s ad. Not so for three of today’s examples. Here, spyware completely fakes a click — causing Yahoo to charge an advertiser a “pay-per-click” fee, even though no user actually clicked on any pay-per-click link. This is “click fraud.”

This document offer four fully-documented examples of improper ad displays (1, 2, 3, 4), including three separate examples showing click fraud. I then develop a taxonomy of the problem and suggest strategies for improvement.

The Pay-Per-Click Promise; The Click Fraud Threat

When advertisers buy pay-per-click advertising, they largely expect and intend to buy search engine advertising. If a user goes to Yahoo and types a search term, interested advertisers want their ads to be shown. Ads are supposed to be carefully targeted, i.e. to the specific keywords advertisers specify. And an advertiser is only supposed to pay Yahoo when a user actually clicks the advertiser’s ad.

Click fraud attacks these promises. In canonical click fraud, one advertiser repeatedly clicks a competitor’s ads — or hires others to do so, or builds a robot to do so. Deplete a competitor’s budget, and he’ll leave the advertisement auction. Then the first advertiser can win the advertising auction with a lower bid.

Advertisement syndication also creates a risk of click fraud. Suppose Yahoo contracts with some site X to show Yahoo’s ads. If a user clicks a Yahoo ad at X, Yahoo commits to pay X (say) half the advertiser’s payment to Yahoo. Then X has an incentive to click the Yahoo ads on its site — or to hire others to do so, or to build robots to do so.

Spyware syndication falls within the general problem of syndication-based click fraud. Suppose X, the Yahoo partner site, hires a spyware vendor to send users to its site and to make it appear as if those users clicked X’s Yahoo ads. Then advertisers will pay Yahoo, and Yahoo will pay X, even though users never actually clicked the ads.

The following three examples show specific instances of spyware-syndicated PPC click fraud. In each example, I present video, screenshot, and packet log proof of how spyware vendors and advertisement syndicators defraud Yahoo’s advertisers.

Click Fraud by 180solutions, Nbcsearch, and eXact Advertising – December 17, 2005

The money trail – how funds flow from advertisers to Yahoo Overture to 180solutions

On a test PC with 180solutions (among other unwanted software) (widely installed without consent), I browsed Nashbar.com, a popular bicycling retailer. I received a popup that immediately forwarded traffic to a Yahoo Overture PPC link — faking a click on that link, and charging an advertiser as if a user had clicked on that link, even though I had not actually done so.

Reviewing my packet log, I see that traffic flowed as listed below.

http://tv.180solutions.com/showme.aspx?keyword=bicycle%2aparts+cycling+cycling…

http://popsearch.nbcsearch.com/metricsdomains.php?search=mountain+bike

http://ww3.exactsearch.net/red.php?mc=T%2FcbeGxGNus4%2F3AyiyVWsqV5cRprOptbkiRR…

http://ww3.exactsearch.net/click.php?mc=T%2FcbeGxGNus4%2F3AyiyVWsqV5cRprOptbki…

http://207.97.227.18/clk/?31303b313133343836343333352e39347e74696572313b3030

http://www22.overture.com/d/sr/?xargs=15KPjg149StpXyl%5FruNLbXU7Demw1X18j2tJ5w…

http://clickserve.cc-dt.com/link/click?lid=43000000005485843

http://www.sportsmansguide.com/affiliate/ccx.asp?url=http%3A%2F%2Fshop%2Esport…

See also full packet log, annotated screenshots, and video.

As shown in the diagram at right, the net effect of these practices is that advertisers pay Yahoo, then Yahoo pays eXact Advertising (eXactSearch), which pays Nbcsearch, which pays 180solutions.

All these payments are predicated on a user purportedly clicking an ad — but in fact no such click ever occurred. Because advertisers are charged for pay-per-click “clicks” without any such click actually taking place, this is an example of click fraud.

Click Fraud by 180solutions, Nbcsearch, and Ditto.com – March 2, 2006

The money trail – how funds flow from advertisers to Yahoo Overture to 180solutions

On a test PC with 180solutions (among other unwanted software) (widely installed without consent), I browsed SmartBargains.com, a popular discount retailer. I received a popup that, in its title bar, indicated that it came from 180solutions. Mere seconds later, I was redirected to a duplicate window of SmartBargains.

Reviewing my packet log, I see that traffic flowed as listed below.

http://tv.180solutions.com/showme.aspx?keyword=%2esmartbargains%2ecom+smart+…

http://popsearch.nbcsearch.com/metricsdomains.php?search=smartbargains.com

http://ww2.ditto.com/red.php?mc=T%2FgSdHBNM%2Bg2%2B3AyiyVWsqV5cRprOptbkiRRrZ…

http://ww2.ditto.com/click.php?mc=T%2FgSdHBNM%2Bg2%2B3AyiyVWsqV5cRprOptbkiRR…

http://agentq.ditto.com/click.clk?pid=708811&ss=smartbargains.com&advname=sm…

http://www24.overture.com/d/sr/?xargs=15KPjg1%2DpSgJXyl%5FruNLbXU6TFhUBPycz2…

http://www.smartbargains.com/default.aspx?aid=47&tid=82136

See also full packet log, annotated screenshots, and video.

As shown in the diagram at right, the net effect of these practices is that advertisers pay Yahoo, then Yahoo pays Ditto.com, which pays Nbcsearch, which pays 180solutions.

All these payments are predicated on a user purportedly clicking an ad — but in fact no such click ever occurred. Because advertisers are charged for pay-per-click “clicks” without any such click actually taking place, this is an example of click fraud.

This example also shows what I call “self-targeted traffic.” Notice that the net effect of this click fraud is to show the user the site the user had requested — but to show that site also in a second (“double”) window. Since users end up at the requested site, users may not notice that anything is wrong. But from an advertiser’s perspective, something is very wrong: This process asks SmartBargains to pay Yahoo Overture PPC fees for SmartBargains’ own organic traffic — a lousy deal, since Yahoo Overture is providing SmartBargains with no new leads and no genuine value.

Click Fraud by Look2me/Ad-w-a-r-e, Improvingyourlooks.com, and Two Unknown Parties – April 1, 2006

The money trail – how funds flow from advertisers to Yahoo Overture to Look2me / Ad-w-a-r-e

On a test PC with Look2me/Ad-w-a-r-e (among other unwanted software) (installed without my consent), I received a popup that redirected me to and through a Yahoo Overture PPC link. The popup ultimately showed me the lasikcookeye.com site even though I had showed no prior interest in eye problems or eye surgery. Reviewing my packet log, I see that traffic flowed as listed below:

http://www.ad-w-a-r-e.com/cgi-bin/UMonitorV2

http://64.194.221.33/cgi-bin/KeywordV2?query=4047&ID={…}

http://12.129.178.27/redir?aid=1006&cid=162&xargs=ZmlkPTUxJmtleT1sYX…

http://search.improvingyourlooks.com/index.html?red=1&q=lasik%20eye%20su…

http://search.improvingyourlooks.com/?1143930576

http://64.14.206.59/cgi-bin/feedred?c=2188&p=2068&q=lasik%20eye%20surgery&de…

http://www10.overture.com/d/sr/?xargs=15KPjg17hS%2DZXyl%5FruNLbXU6TFhUBQxd7t…

http://www.lasikcookeye.com/

See also full packet log, annotated screenshots, and video.

As shown in the diagram at right, the net effect of these practices is that advertisers pay Yahoo, then Yahoo pays the operators of the server at 64.14.206.59, which pays improvingyourlooks.com, which pays 12.129.178.27, which pays Ad-w-a-r-e.

All these payments are predicated on a user purportedly clicking an ad — except that in fact no such click ever occurred. Because advertisers are charged for pay-per-click “clicks” without any such click actually taking place, this is an example of click fraud. Furthermore, because my prior activity gave no sign of any interest in eye care, this popup sends the advertiser untargeted traffic — also contrary to Yahoo’s representations to advertisers.

Advertiser Lasikcookeye is the victim of these practices and the victim of this click fraud. Lasikcookeye contracted with Yahoo to buy pay-per-click ads shown at Yahoo.com when users performed relevant searches. Lasikcookeye intended (and reasonably expected) that its ad would be shown to appropriate users, and that it would only be charged if a user saw the ad, found it appealing, and specifically chose to click on it. Instead, Lasikcookeye here was charged for a “click” that never took place, and for its site being shown to a user who never asked to see it. Furthermore, Lasikcookeye’s site was shown in a popup, an advertising format users are known to dislike, which risks damaging Lasikcookeye’s good name.

Unlabeled PPC Links Inserted into Third Party Web Sites – by Qklinkserver.com / Srch-results.com, Searchdistribution.net, and Intermix’s Sirsearch – April 2, 2006

The circled link was inserted into the nytimes.com site by Qklinkserver, without the Times’ consent. Clicking the link sends traffic to Yahoo Overture PPC and on to an advertiser.

The circled link was inserted into the nytimes.com site by Qklinkserver, without the Times’ consent. Clicking the link sends traffic to Yahoo Overture PPC and on to an advertiser.

The money trail – how funds flow from advertisers to Yahoo Overture to Qklinkserver

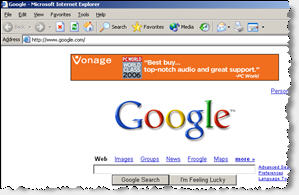

On a test PC with Qklinkserver (among other unwanted software) (installed without my consent), I observed numerous extraneous hyperlinks inserted into third parties’ sites. Checking these same sites on ordinary uninfected PCs, I received no such links. See e.g. the partial screenshot at right, showing an extra hyperlink inserted into the lead article listed on the New York Times site.

Clicking that extra New York Times link yielded traffic to a Yahoo Overture PPC link and on to a Yahoo Overture advertiser (here, shop.com). Reviewing my packet log, I see that traffic flowed as listed below:

http://www.qklinkserver.com/lm/rtl4.asp?si=20057&k=prime%20minister

http://search1.srch-results.com/search.asp

http://partnernet.searchdistribution.net/go3.aspx?encr=1&nv_click=9JT5m1b…

http://www.sirsearch.com/click.cfm?rurl=http%3a%2f%2fwww10.overture.com%2…

http://www10.overture.com/d/sr/?xargs=15KPjg1%5F5SjJXyl%5FruNLbXU6TFhUBPz…

http://www.shop.com/op/aprod-~Prime+Minister+Print?ost=prime+minister&sou…

See also full packet log, annotated screenshots, and video.

As shown in the diagram at right, the net effect of these practices is that advertisers pay Yahoo, then Yahoo pays Intermix (Sirsearch), then Intermix pays Searchdistribution.net which pays Qklinkserver.com / Srch-results.com.

As shown in the inset image above-right, Qklinkserver.com inserts links into other sites without any on-screen indication that the links come from Qklinkserver, not from the requested sites. Users seeing such links might reasonably think they reflect editorial selection by the requested sites (i.e. New York Times editors picking an appropriate link), when in fact the links merely point to whichever advertisers bid highest at Yahoo.

Note that traffic passes through Intermix’s Sirsearch servers. This is not Intermix’s first involvement with spyware, nor Intermix’s first involvement with Yahoo in the context of spyware. During the New York Attorney General’s summer 2005 investigation of Intermix for improper installation of advertising software onto users’ computers, a NYAG investigator reported that more than 10% of Intermix’s revenues came from Yahoo. The investigator further commented that the NYAG was “not ruling out … going after … Overture” for its role in funding Intermix. My findings here suggest that Intermix’s relationship with Yahoo and Intermix’s funding of spyware may extend beyond what was previously known.

I have tested the Qklinkserver advertising software at length. Of the links I have received from Qklinkserver, every single one ultimately passes through Yahoo Overture. As best I can tell, Yahoo Overture is the sole source of funding for Qklinkserver. (Compare: Yahoo Overture funding 31% of Claria, per Claria’s 2003 SEC S1.)

Understanding the Problem

I see six distinct problems with the Yahoo practices and partners at issue.

- Click fraud. Through these improper ad displays, Yahoo charges advertisers for “clicks” that didn’t actually occur. This violates the core premise of pay-per-click advertising, i.e. that an advertiser only pays if a user affirmatively shows interest in the advertiser’s ad. Yahoo promises: “Pay only when a customer clicks on your listing.” But that’s just not true here. Instead, through click fraud, advertisers are asked to pay for spyware-delivered traffic, whether or not users actually click.

- Untargeted traffic. Premium prices for PPC advertising reflect, in part, the extreme targeting of PPC leads: PPC ads are only supposed to be shown to users actively searching for the specified product, service, or term. Yahoo promises: “Advertise only to customers who are already interested in your products or services.” That’s also untrue in some of my examples. in fact spyware-delivered PPC results show Yahoo PPC ads to users with no interest in advertisers’ products or services.

- Self-targeting traffic. Spyware-delivered PPC ads often target advertisers with their own ads. For example, in August I reported a user browsing the Dell site, then receiving spyware-delivered Yahoo PPC advertising promising “up to 1/3 off” if a user clicked a prominent link. But clicking that link didn’t actually provide any discounts or savings beyond Dell’s usual prices. However, each time a user clicked the link, Dell had to pay Yahoo a PPC advertising fee that I estimate at $3.30. That’s a bad deal for Dell: These users were already at Dell’s site, and there’s no reason why Dell should pay Yahoo or a spyware vendor just to keep them there. Same for self-targeting of SmartBargains, reported above.

- Failure to label sponsored links as such. Through spyware syndication, Yahoo PPC ads often appear on users’ screens without appropriate labeling. When unlabeled ads appear in or adjacent to search engine results, these ads risk violating the FTC‘s 2002 instructions for advertising disclosures at search engines. See my prior SideFind example, where SideFind justifies bona fide search results with Yahoo PPC ads, without labeling Yahoo’s ads as such. Unlabeled ads also prevent users from understanding the nature of the linked content: For example, recall my Qklinkserver example. Seeing unlabeled text links inserted into ordinary web pages, users reasonably expect that such links were chosen by the sites users were visiting, when in fact such links were unilaterally inserted by unrelated spyware installed without user consent.

- Low-quality traffic. Advertisers pay Yahoo a premium to reach desirable users at Yahoo.com — sophisticated users, users who are actively engaged in search. In contrast, spyware sends advertisers low-quality users, including users who are less likely to make a purchase. This traffic is not worth the premium price Yahoo charges. Consider: 180solutions sells popups for as little as $0.015 (one and a half cents) per ad display. In contrast, Yahoo charges a minimum of $0.10 — more than six times as much. Yahoo harms advertisers when Yahoo charges advertisers its premium prices for ads ultimately shown through low-quality low-cost channels like 180solutions.

- Unethical spyware-sourced traffic. Industry norms, litigation, and instructions from policy makers (1, 2) all tell advertisers to keep their ads out of spyware. Discomfort with spyware reflects concerns about installation methods (misleading and nonconsensual installations), privacy effects, other harms to consumers, and harms to other web sites. For these and other reasons, many advertisers make a serious good-faith effort to stay away from spyware. These same advertisers also buy PPC ads from Yahoo — a standard, reasonable practice for anyone buying online advertising. Unfortunately, these Yahoo PPC ad purchases inevitably and automatically put advertisers into notorious spyware, including the programs reported above. By allowing these improper ad placements, Yahoo endangers its advertisers’ good names, and risks putting them in violation of best practices and policy-makers’ guidance.

Each of these problems is serious in its own right. But the examples at hand, in my current and prior reporting, inevitably combine several such problems — making them particularly troubling. The table below attempts to summarize my findings, as to the specific examples reported above and previously.

* – These examples entail click fraud — with nothing shown to a user before a PPC ad was invoked, and hence no opportunity for improper ad labeling.

An empty box should not be taken to be an endorsement of a vendor’s practices, or an indication that that vendor does not perform the specified practice. For example, although I have not chosen to post an example of eXact Advertising harming merchants via self-targeting, I have observed such self-targeting.

Yahoo’s Click Fraud and Syndication Fraud in Context

Many others have alleged click fraud at Yahoo. (1, 2, 3) But others generally infer click fraud based on otherwise-inexplicable entries in their web server log files — traffic clearly coming from competitors, from countries where advertisers do no business, or from particular users in excessive volume (i.e. many clicks from a single user). In contrast, my proof of click fraud is direct: As documented and linked above, I have captured click fraud on video and in packet logs. Yahoo may argue about advertisers’ inferences in other instances, i.e. disputing that advertisers have really found click fraud. But it’s far harder to deny the click fraud shown in my examples.

In the examples I show above and previously, Yahoo’s problem results from bad partners within its network. Yahoo syndicates ads to numerous partners, many of whom syndicate ads to others, some of whom then syndicate ads still further. The net effect is that Yahoo does not know who it’s dealing with, and therefore cannot exercise meaningful supervision over how its ads are displayed. I consider this a bad idea — bad business, bad for quality, bad for accountability. But Yahoo need not listen to me. Instead, consider instructions from New York Attorney General staff member Ken Dreifach: “Advertisers and marketers must be wary of fraud or deceptive practices committed by their affiliates, even [affiliates] that they have no working relationships with.” (Quote from MediaPost, summarizing Dreifach’s remarks.)

Yahoo’s “Whack-A-Mole” Problem

The many bad partners in Yahoo’s network make fraud particularly hard to block: When Yahoo terminates one fraudster, that fraudster’s partners find another way to continue operations.

Notice that the first and second examples (above) both show click fraud that originates with 180solutions and Nbcsearch. Yet Nbcsearch’s relationship with Yahoo Overture differs between these two examples: In the first, Nbcsearch gets ads from eXactSearch which gets ads from Yahoo; in the second, Nbcsearch instead gets Yahoo ads from Ditto.com. My testing suggests that Yahoo may have terminated the former ad channel at some point after my December testing. But Nbcsearch’s efforts to defraud Yahoo advertisers were not stymied by Yahoo’s possible termination of the first channel; Nbcsearch was able to find a new channel, i.e. Ditto.com, by which to continue to perform click fraud.

Yahoo’s enforcement difficulties are also borne out in its unsuccessful attempts to sever ties with 180solutions and Direct Revenue. After I highlighted these vendors in my August report, it seems Yahoo attempted to terminate its relationships with them. Yet 180 continued not just to show Yahoo ads, but also to perform click fraud, as documented in the first two examples above. Furthermore, as recently as February 2006, I have continued to see Direct Revenue serving popups that ultimately show Yahoo PPC ads. So even when Yahoo seeks to sever relationships with a partner as well-known as 180solutions or Direct Revenue, it seems Yahoo is unable to do so.

What Comes Next

After my August report, Yahoo terminated several of the specific wrongdoers I identified. I expect and hope that Yahoo will respond similarly to the findings reported here. If I learn of such a response, or if I receive any other relevant communication from Yahoo, I will update this page accordingly.

But it is not a sustainable approach for me to perform occasional public audits for Yahoo. These reports are infrequent, hardly sufficient to protect advertisers from ongoing fraud. Furthermore, these reports are merely illustrative — giving a few examples of a broad class of problems, but reporting only a small proportion of the fraud of which I am aware.

Yahoo recently announced its support (as a founding sponsor) of TRUSTe‘s forthcoming Trusted Download Program. The Trusted Download program intends to certify advertising software — so advertisers can confidently buy ads from such programs. I have a variety of concerns about the program — including that its standards may be too lax, that it will face exceptional difficulties in performing meaningful enforcement, and that I don’t know that any “adware” deserves a certification or endorsement. But even if Trusted Download were fully operational and working as expected, it would not have identified or prevented the problems described in this article. At best, Trusted Download would tell Yahoo that it may work with whatever adware vendors earn TRUSTe’s certification. But Yahoo’s problem isn’t uncertainty about which adware vendors are good. Instead, Yahoo’s problem is that, time and time again, it finds itself working with (and its advertisers defrauded by) notorious “adware” vendors — vendors Yahoo has already resolved to avoid (e.g. 180solutions, Direct Revenue), or vendors that wouldn’t come close to passing any ethics test (e.g. Qklinkserver, Look2me/Ad-w-a-r-e). Trusted Download doesn’t and won’t monitor advertisement syndication; Trusted Download won’t and can’t prevent these bad Yahoo PPC syndication relationships.

I see two basic strategies for Yahoo. Yahoo could try to limit its exposure to fraud, i.e. by scaling back its partner network, by more thoroughly vetting its partners, and by prohibiting its partners from further resyndicating Yahoo’s ads. Alternatively, Yahoo could try to detect fraud more thoroughly and more quickly, i.e. by implementing aggressive and robust testing methods to find more examples like those above, and like the dozens more examples I have on file. I tend to think both strategies are appropriate; in combination, they might serve to blunt this growing problem. But merely ignoring the issue is not a reasonable option; Yahoo’s advertisers pay top dollar for Yahoo PPC ads, and they deserve better.

Yahoo cannot expect these fraudulent techniques to disappear. Yahoo is an attractive target for fraudsters due to Yahoo’s high advertising charges and Yahoo’s high payments to partners. As spyware vendors find other revenue sources increasingly difficult (i.e. because advertisers do not want to buy spyware-delivered advertising), spyware vendors are likely to continue to turn to more complex advertising channels such as PPC, which are more amenable to fraud due to their reduced transparency and increased complexity. Yahoo, like other PPC services, needs to anticipate and block this growing problem.

Similar issues confront Google — though, in my testing, more often through bad syndication and less often through click fraud. I’ll cover Google’s problems in a future piece. Meanwhile, see my prior articles about Google and spyware: 1, 2.

The Direct Revenue ad, edited to cover explicit areas.

The Direct Revenue ad, edited to cover explicit areas.