Some analysts view affiliate marketing as “fraud-proof” because affiliates are only paid a commission when a sale occurs. But affiliate marketing nonetheless gives rise to various disputes — typically, merchants alleging that affiliates claimed commission they had not properly earned. Most such disputes are resolved informally: merchants withhold amounts affiliates have purportedly earned but have not yet received. Occasionally, disputes end up in litigation with public availability of the details of alleged perpetrators, victims, amounts, and methods. This page presents known litigation in this area including case summaries and primary source documents.

Uber Technologies v. Hydrane SAS et. al.

Superior Court of California, County of San Francisco – Civil Case No. CGC19576493 – June 5, 2019

Core allegation: Placing Uber ads in prohibited sites and claiming commission on signups that were going to happen anyway

Factual allegations: See docket.

Amount in dispute: $70 million. (See second amended complaint, paragraph 91.)

Settled, May 2021.

Mary Kay Inc. v. Retailmenot, Inc.

U.S. District Court for Northern District of Texas – Civil Case No. 3:15-cv-00825-L – March 13, 2015

Core allegation: RMN purports to aggregate digital coupons, including from affiliate programs. RMN falsely claims to provide coupons for MK.

Legal claims: Trademark infringement, Unfair competition, False advertising, Trademark dilution

United States of America v. Allen J. Chiu and Andrew S. Chiu

U.S. District Court for Western District of Washington – Criminal Case No. CR12-070-RSM – March 14, 2012

Core allegation: Fake orders for affiliate commission. See indictment.

Charges: Fraud by Wire, Radio, or Television (18 USC § 1343)

Victims: Fatwallet, Nordstrom

Affiliate Network: LinkShare

Indictment alleges that Nordstrom initially disallowed the Chius from making purchases due to their excessive claims for merchandise purportedly lost in transit.

Indictment alleges that the Chius later noticed that their further orders continued to yield Fatwallet cashback credit even though Nordstrom correctly canceled the orders and never charged the Chius’ credit cards. The Chius placed additional orders totaling approximately $23 million in order to receive Fatwallet cashback on those purchases.

Complaint alleges that the Chius made multiple attempts to obtain their Fatwallet balance purportedly earned, including changing payee names, payee addresses, and payment methods.

The report of FBI investigator Cory Cote says the Chius obtained 787 separate checks from Fatwallet, sent to three different names at five different mailing addresses, using eighteen different Fatwallet accounts. Cote says the Chius’ orders from Nordstrom used 58 different credit cards.

After Fatwallet blocked the Chius’ withdrawals, Cote reports that the Chius attempted to collect cashback via Ebates, another cashback site. Despite using five different Ebates accounts, the Chius never received any funds from Ebates.

Amount in dispute:

Indictment alleges $1.4 million taken from Nordstrom. Of this amount, a portion was retained by Fatwallet and LinkShare as service fees, and the indictment reports the Chius receiving more than $650,000 of cashback from Fatwallet.

FBI investigator Cory Cote says the Chius caused transactions yielding more than $2 million of commissions and more than $1.1 million of cashback.

Indictment reports approximately $971,000 seized from the Chiu’s personal and retirement accounts.

An August 2012 itemization indicates $1,413,525 paid by Nordstrom to FatWallet and an additional $157,303 paid by Nordstrom to LinkShare (of which LinkShare credited back $103,342 but retained $53,961.

Statement from Defendants: Defendants’ friends and colleagues filed ten letters in support of defendants’ character. (1, 2) Letter-writers: Albert Cheng of Google, Edwin Altomare, Calli Lewis of the University of North Texas, Hua Maggie Sun-Rubin of AT&T, Guillermo Perez-Vega of Trammell Crow Company, Scott Smith of Southern California Edison, Nitin Patel of ComEd, John Rusnak of ComEd, Ronald Hart of ComEd, and Bill Frederick.

Disposition:

Federal sentencing guidelines specified a sentencing range of 33-41 months (after adjustment for defendants’ lack of criminal history). The United States recommended 24 months and the court so ordered (Allen, Andrew).

Defendants forfeited “nearly all of their life savings”, totalling $971,810.86 (including funds earned from legitimate sources).

Defendants sought to avoid repaying amounts that were lost to Nordstrom but never received by Defendants (i.e. fees retained by FatWallet and LinkShare). The United States argued that these are part of Nordstrom’s loss and hence a required part of restitution. The Court ordered that restitution include the FatWallet and LinkShare fees without any offset for amounts those companies might return to Nordstrom.

Companion civil case by victim FatWallet:

Fatwallet, Inc. v. Andrew Chiu and Allen Chiu – complaint

U.S. District Court for Western District of Wisconsin – Civil Case No. 3:12-CV-00012-WMC – January 5, 2012

Legal claims: Theft by Fraud, Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), Breach of Contract, Unjust Enrichment

Fatwallet complaint says Fatwallet is “exposed to a claim” that it repay Nordstrom.

United States of America v. Christopher Kennedy

U.S. District Court for Northern District of California – Criminal Case No. 5-10-CR-00082-JW. February 9, 2010

Core allegation: Writing software to perform cookie-stuffing. Information/complaint.

Victim: eBay

Affiliate Network: eBay Partner Network

Legal claim: Conspiracy to Commit Wire Fraud

Information alleges that Kennedy created a program, “Saucekit,” to assist eBay affiliates in performing cookie-stuffing. Alleges that Kennedy conspired with those affiliates in defrauding eBay.

Kennedy routed cookie-stuffing traffic via the many and seemingly-unrelated affiliate links of the various purchasers of Kennedy’s Saucekit program.

Amount taken from victim: Information reports multiple Saucekit customers earning substantial commissions, including one nearing $10,000 per month.

Disposition: In a June 2012 plea agreement, Kennedy was sentenced to six months in prison and ordered to pay $407,934.39 to eBay in restitution. He was scheduled to begin serving his prison sentence on September 20, 2012.

Five separate cases as to Brian Dunning, Todd Dunning, Shan D. Hogan, Digital Point Solutions, Kessler’s Flying Circus, and Thunderwood Holdings – cookie-stuffing targeting eBay via Commission Junction

Case captions:

United States of America v. Brian Dunning. U.S. District Court for Northern District of California, Criminal Case No. 5:10-CR-00494-EJD, June 24, 2010. indictment and superseding information

eBay Inc. v. Brian Dunning; Thunderwood Holdings, Inc.; and Kessler’s Flying Circus. U.S. District Court for Northern District of California, Civil Case No. CV 08-4052-EJD-PSG, August 25, 2008. complaint

Commission Junction, Inc. v. Thunderwood Holdings, Inc. dba Kessler’s Flying Circus; Todd Dunning; Brian Dunning. Superior Court of the State of California for the County of Orange, Central Branch, Civil Case No. 30-2008 00101025. January 4, 2008. second amended complaint

United States of America v. Shawn D. Hogan. U.S. District Court for Northern District of California, Criminal Case No. 5:CR-10-0495-JF, June 24, 2010. indictment

eBay Inc. v. Shawn Hogan and Digital Point Solutions, Inc. U.S. District Court for Northern District of California, Civil Case No. CV 08-4052-EJD-PSG, August 25, 2008. complaint

Core allegation: Affiliate cookie-stuffing

Legal claims: Criminal charges against Dunning and Hogan: Wire Fraud Act; eBay civil charges against Dunning, Thunderwood Holdings, and Kessler’s Flying Circus, and Hogan: Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), California § 502 (Computer Tampering), Restitution and Unjust Enrichment, California Business and Professions Code, Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO Act); Commission Junction civil charges: Breach of Contract, Open Book, Account, Reasonable Value, Conversion, Unfair Competition, Declaratory Relief

Indictments allege (Dunning, Hogan) that when users visited any of “a large number of web pages,” Defendants caused users’ computers to send requests to eBay reporting, falsely, that Defendant had referred them to eBay. Alleges that this occurred invisibly and without user knowledge. Alleges that when users happened to make purchases from eBay or open eBay accounts, Defendants collected marketing commissions. eBay complaint is in accord.

CJ complaint alleges that Defendants provided third parties with a widget placed on other sites, including on MySpace (allegedly in violation of MySpace terms) which wrongfully forced traffic to eBay.

Internal CJ correspondence reveals that CJ learned of Defendants’ infractions via a complaint from eBay, not via independent CJ investigations.

Methods of concealment:

eBay complaint alleges that Defendants used images on web pages to effectuate its cookie-stuffing scheme and intentionally set these images to be so small as to be effectively invisible.

eBay complaint alleges that Defendants only stuffed cookies once per user computer in order to avoid discovery by eBay or Commission Junction.

Indictments allege (Dunning, Hogan) that Defendants intentionally declined to stuff cookies to users near headquarters of eBay and Commission Junction. eBay complaint is in accord.

Dunning indictment alleges that Defendant knowingly misrepresented that his methods were “in line with” affiliate program rules.

The FBI report from interviewing Shawn Hogan presents Hogan’s statements as to Dunning, including Hogan claiming Dunning “reverse engineer[ed]” Hogan’s tools and “rip[]ped off” some of Hogan’s tools. The associated search warrant (for search of Hogan’s residence) includes details of the FBI’s initial suspicions about Dunning, including a complaint from eBay.

Hogan indictment alleges that when Commission Junction representatives questioned Hogan about cookie-stuffing, he falsely attributed suspicious activity to “coding errors.”

eBay civil complaint alleges that Defendants only stuffed cookies once per user computer in order to avoid discovery by eBay or Commission Junction.

eBay civil complaint alleges that Defendants presented their JavaScript code in a way intended to “obscure[] the purpose and effect” to hinder investigation.

See also a declaration of an FBI agent who searched Hogan’s home, as well as 88 pages of additional material including search warrant (with details of the FBI’s initial suspicions and complaint from eBay), report from the search (including Hogan’s statements during the search), and pictures of Hogan’s home.

Amount at issue:

Dunning indictment alleges more than $5,300,000 in compensation from January 2006 to June 2007.

Hogan indictment alleges more than $15,500,000 in compensation from January 2006 to June 2007.

CJ civil complaint alleges that eBay did not pay CJ $565,517.84 despite CJ paying that amount to Defendants. CJ sought repayment of that amount by Defendants to CJ.

Defendant Dunning’s statements:

A Partial Explanation – Brian Dunning, October 5, 2011. – Describes Brian’s understanding of the meaning of cookie-stuffing: “Take any web browser, erase all its cookies, and adjust its security preferences to allow third party cookies. Then, click through a few pages on any ad-supported web site, like Slate.com or HuffPo.com. Now look at your cookies. You’ll see that your browser is loaded with all sorts of cookies from strange web sites that you don’t recognize. That’s cookie stuffing. It’s a scary-sounding term, but it’s fundamental to the way Internet advertising works.”

References Brian’s anticipated defenses: “Obviously there are many intricacies here that go deeper, but I cannot give further details. There are several legal reasons that the lawsuit is improper, and we’ve been fighting it on that basis. Hopefully it will never go to trial, but if it does, my defense depends on evidence that I cannot describe publicly. It’s quite an amazing story, and I look forward to telling it in full detail as soon as the circumstances make it possible.”

The FBI report from interviewing Dunning (attached to the United States’ opposition to Dunning’s motion to suppress evidence) includes Dunning’s statements that eBay’s affiliate program was “stupid”, and that he was “clever” in finding a way to take advantage of the program. The FBI agent interviewing Dunning reports that Dunning admitted using a 1×1 pixel to force an eBay cookie with his affiliate codes.

Dunning claims that a former CJ employee, Andrew Wey (spelling uncertain) provided inside information regarding how to take advantage of eBay’s affiliate program. Dunning claims he paid Wey ten percent of the money he made from eBay.

Defendant Hogan’s Statements:

What Does Carmen Electra, Cyber-Terrorism and Meg Whitman Have In Common? eBay! – Shawn Hogan, August 2, 2010.

Says he promoted eBay ” using a small percentage of the [Digital Point] Ad Network ad space to serve up tens of millions of eBay ads every day.” Attributes increased eBay commissions to these placements.

As to violations of eBay’s rules: “When I asked [eBay staff] why they … allow affiliates to violate their terms of service, they … avoid[ed] answering my actual question. Finally [they] informed me that their terms of service (and even the entire affiliate program to some degree) was a bit of a facade. It allowed eBay to do things they wanted to do (like spam search engines, deploy in countries where they had no actual presence, etc.), while also giving them a way to wash their hands of any wrong-doing when any of their large partners (like Google) would question them about it (like why there are so many spam sites directing people to eBay).” Says eBay staff gave him suggestions on how to avoid being flagged in compliance reports by outside examiners.

As to relationships with eBay staff: Says he gave one eBay employee $50,000 to buy a new car, and gave others a plasma TV, new laptop, etc.

Disposition:

In an arraignment of April 15, 2013, Dunning entered a guilty plea. In sentencing proceedings, the United States sought 27 months imprisonment of . In a decision of August 4 , 2014, the Court ordered 15 months imprisonment to begin September 2, 2014.

In a December 17, 2012 hearing, Hogan pled guilty. In an April 30, 2014 judgment, Hogan was sentenced to five months imprisonment, three years of supervised release, and a $25,000 fine.

Pursuant to a settlement dated March 9, 2009, Defendants paid CJ $25,000.

Lands’ End, Inc. v. Eric Remy, Thinkspin, Inc., Braderax, Inc., and Michael Seale

U.S. District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin – Civil Case No. 05-C-368-C. September 1, 2006

Core allegation: Affiliate typosquatting – Decision on Motion to Dismiss

Victim: Lands’ End

Affiliate Network: LinkShare

Legal claims: Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (ACPA), Lanham Act, Wisconsin Stat. § 100.18 (Fraudulent Representations), Breach of Contract, Fraud

Plaintiffs alleged, and Court found, that defendants registered thirteen typosquatting domains targeting Lands’ End marks (e.g. lnadsend.com) and redirected traffic from these domains to Lands’ End affiliate links.

Plaintiffs alleged, and Court found, that Defendants were approved as Lands’ End affiliates based on information they provided about the non-typosquatting websites they purported to operate (e.g. www.savingsfinder.com). Defendants failed to disclose their use of the typosquatting domains.

Plaintiffs alleged, and the Court found, that Defendants redirected through Lands’ End affiliate links at most once per user, and subsequently (falsely) said the site was “unavailable” due to “technical difficulties.” As a result, a user or investigator seeking to reproduce a finding might be unable to do so.

Amount at issue: Marketing commissions: Thinkspin ($6,698), Braderax ($500), and Seale ($26); Default judgment of $153,437.50 of actual damages, statutory damages, and attorneys fees.

For additional discussion of some of these practices, see Information and Incentives in Online Affiliate Marketing.

Please send additional cases or notable documents to Ben Edelman.

Thanks to Irene Chen for assistance in gathering and summarizing selected documents.

Last updated: June 9, 2025

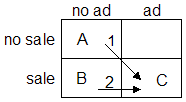

Revenue Counterfactual

Revenue Counterfactual

ExitExchange, another banner farm, as shown by a SurfSidekick popup.

ExitExchange, another banner farm, as shown by a SurfSidekick popup.